An APP(le) a Day: Can Smartphones Provide Smart Medical Advice?

I am not going to shock anyone by stating that we live in a time where distrust of government is high, where people believe that they need to ‘take back’ whatever they feel needs taking back. This opinion runs especially strong in matters surrounding healthcare, where people question a range of issues, including: universal insurance, low cost pharmaceuticals, the efficacy of particular medical tests, and autonomy as regards end of life (and other medical) decisions.

Despite the fight over what ails our medical system, all parties seem to agree on (at least a part of) the cure, mobile medical applications (MMAs), also known as medical apps. How can these groups agree? Well, they really don’t. While some medical providers and government initiatives (including England’s National Health Service Modernization Project and the United States’ Affordable Care Act) envision these pieces of technology as ways to monitor health remotely (allowing for more proactive and less drastic medical interventions), insurance companies believe that those same apps will replace many basic tests and give medical consumers answers to questions without having to admit them to hospitals (thereby trimming costs). Medical schools see apps as low cost educational adjuncts, while, according to a recent ITN study, over 2/3 of American medical consumers hope that they can buy (or lease) their own primary care iPhysician, whether to monitor or take charge of their health, or to free themselves from their reliance on (or belief in) the medical establishment.

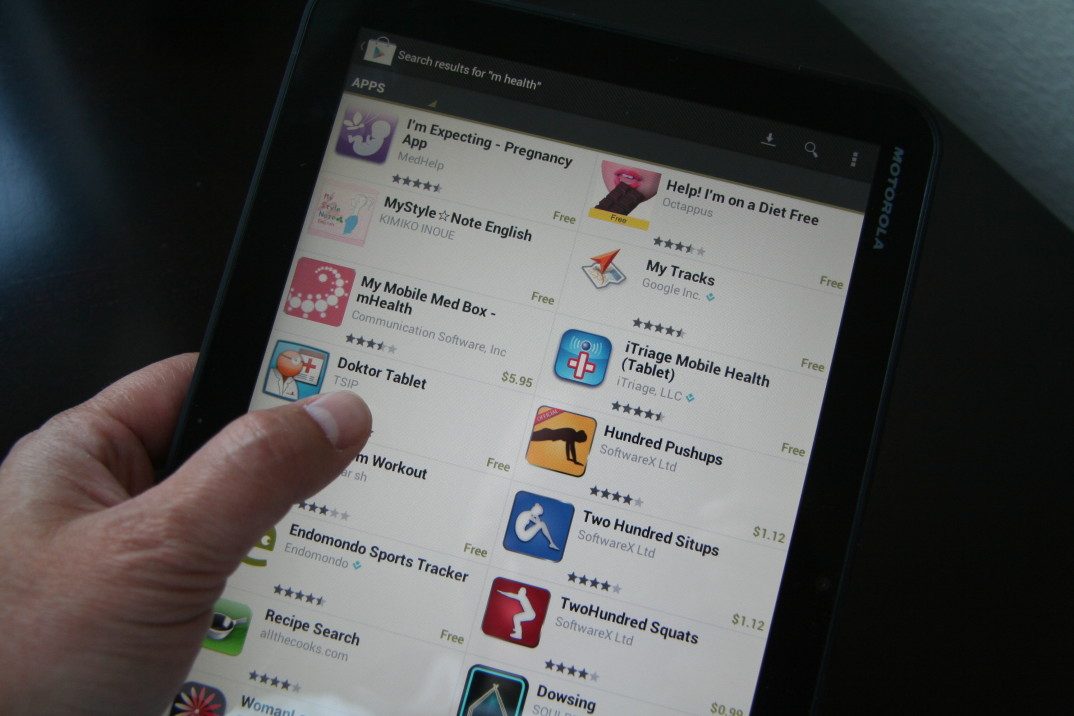

Regardless of rationale, medical apps (and the larger ‘healthcare apps’ category) are big business. According to a recent IMS Health study there were more than 165,000 medical apps available to smartphone users worldwide as of 2015. The question is whether, perhaps, this is a case where everyone can and should simply declare victory. Can medical apps be all things to all people? Are they too good to be true? Can a blog post even begin to answer these questions?

My answer to all of these questions is a resounding ‘maybe.’

As with most pieces of new technology, there is a lot of potential for real good in medical apps. They CAN play a role in significantly reducing medical costs and rates of hospital recidivism, they can help doctors provide more proactive, up to date, medical advice, and they can help both doctors and patients monitor every step, donut, and heartbeat. These are real advances, ones that do more than improving someone’s current health and reduce the number of emergency room visits (and return visits). These data, properly collected and analyzed, can allow a doctor to do a longitudinal studies of a patient’s own health, and with permission, these data can also be used in population-level epidemiological studies to better track disease paths, or the impact of lifestyle and genetic factors on particular conditions. Additionally, as a part of our electronic health records (EHRs), these data can provide a medical team everything they need to know in order to treat you, regardless of whether you can even remember your own blood type. In other words, this is an incredibly cool time to be alive and to own a smartphone.

However, medical apps also can bring significant risks to medical care (some that predate this particular form of medical adjunct, and some that I believe are new). In my remaining time, I would like to introduce a representative (but not in any way exhaustive) discussion of these issues. Although there will be overlap, for the sake of organization I have divided my comments into two categories: consumer side (focused on safety, on conflict of interest, and on regulation) and provider side (focused on the changing role of health care providers and on the twin horns of privacy and access).

Consumer side issues:

The American public has been taught that safety (and efficacy) of care are top priorities for our medical system. Pills and medical equipment go through as tough of scrutiny as do our medical professionals before either are allowed near patients. The problem here is that we believe that medical apps are held to the same standards as other pieces of medical technology.

In part, this confusion is understandable. Lewis and Wyatt pointed out that there has been a lack of clarity regarding when a medical app becomes a formal medical device. The FDA’s response to the problem was to mandate that an app is medical (and potentially subject to regulation) if and only if the developer says that it is. As a result, whether by mistake or intentional omission on the part of its creator, an app that becomes widely used for medical purposes may do so without ever having been tested for safety or efficacy by the FDA.

In addition, the public believes that apps, like medical devices and pharmaceuticals, are made by medical (or scientific) professionals. In fact, there is no such requirement for medical app development, and according to scholars like Buijink, Visser, and Marshall, many of these apps may have been made without any medical or scientific oversight (it is difficult to know this for a fact, as there are no disclosure requirements for apps) and many market themselves as being capable of diagnosing or treating illnesses without providing any evidence to that effect. This lack of medical grounding and transparency does not extend to every medical app, but it is difficult for both consumers and medical professionals to separate the wheat from the chaff.

Along with these supply-side issues, Bellman et al explains that marketing professionals have discovered ways to brand (create more demand for) their apps: “Apps with an informational creative style, which focuses attention on the user, and therefore encouraged personal connections with the brand, were more effective at shifting purchase intention. In contrast, experiential, game-like apps were less successful because they focused attention on the phone” (p. 199). As pharmaceutical and medical device companies have, for years, used similar techniques to connect people to particular medications, it isn’t hard to imagine a time in the near future when commercials will tell you to ‘talk to your doctor’ about a particular app.

Although this activity might seem innocuous, however odious (a claim made about marketing pharmaceuticals), in fact, apps are created and approved using methods that are very different than those used to create medical (e.g. medications or arterial stents), or even quasi-medical treatments (ranging from chicken soup to herbal remedies) in that they need not even prove themselves to be medically safe, much less effective before they can be sold in the app store. Serious questions about the mandate and ability of the FDA to hold apps to medical standards, have lead technophiles and medical professionals worldwide to call for a system to better curate and regulate medical apps.

Provider side issues:

In addition to the aforementioned, healthcare providers have additional causes for concern, For example, when healthcare professionals or medical schools ‘prescribe’ apps to patients or to medical students for training purposes, they need to ask questions about the safety and backing of those apps, both as a matter of best practices and in order to protect them from potential liability if those apps give bad advice.

Additionally, the many health care professionals who use medical apps as a resource are pushing medicine to think about a ‘big picture’ question about the changing nature of healthcare. Where doctors used to be seen (for good or bad) as the ultimate source of healthcare information, now, patients come to doctors with their own ‘diagnoses.’ Thanks to their iPads and other ‘second brains,’ doctors now have more access to cutting edge information on treatment protocols, new medicines, etc., but patients, who have no ability to sift medical information from quackery, demand alternative therapies or diagnoses that are not based on medical evidence. As a result, doctors are shifting from being medical repositories to being seen more as curators of healthcare knowledge, using their iPads and other ‘peripheral brains’ to help them make decisions in ways that they probably couldn’t have imagined when textbooks were the only sources of medical knowledge. Of course, all of this needs to be done by doctors who need to type all of this information into their tablets while still interacting with their patients (within the 20 minutes slot dictated by insurance carriers for a wellness checkup).

Speaking of typing, medical professionals who use apps have to deal with the twin monsters Scylla (privacy) and Charybdis (access) of recordkeeping. Patients want to protect their medical records (via HIPAA regulations) have a really interesting problem here, especially since many apps make money by selling data to other companies. This problem could be exacerbated by the fact that an app could conceivably designate itself as non-medical to avoid these restrictions. On the other hand, medical professionals need to have access to your data, both for remote monitoring of patients and in order to make medical data available to other doctors (when needed), and to be compliant with government mandated EHR policies.

The prognosis?

Given the problems listed above, is there even room for a ‘maybe’?

Despite (or in some cases because) of the issues mentioned above, I am truly excited about the potential that medical apps have to change medical education, practice, and research. Apps have already had a major impact on medicine, changing the roles of medical consumers and practitioners in a variety of ways.

At present, there is a lot of uncertainty surrounding the rules of the game (for app makers, app consumers, medical practitioners, insurance companies, and the US Government). Hopefully, these groups will be able to agree on regulations and best practices that will make medical apps safe and effective without killing innovation, and simultaneously provide private and universally accessible data to only the right people.

So, if you are going to proceed (and let’s be honest, apps are cool, you will proceed), do so with caution. For medical consumers, understand that apps are not the same as aspirin (or even willow bark tea). Ask questions about the makers and consultants on your app. Check to see if there are research studies that have evaluated it (and no, the comments section on the app does not count), and make sure that your data will be under your control. For medical providers (or students), good luck. Your patients are going to use medical apps, whether you like it or not.