Part of Post-World War II policy in Germany was to ban Nazi propaganda and symbols from being displayed. This includes propaganda from the Nazi regime that we commonly see in museums or is shown in history classes. While I found German Holocaust and history museums to be largely well-done and factual despite the restrictions, containing acknowledgment of wrongdoing, one has to wonder whether the ban may actually go too far and be detrimental to education. History has a tendency to repeat itself, and the accepted way to prevent this repetition is to educate the next generations about the past. Germany’s policy is now confronted with that educational and moral dilemma over Nazi texts from an academic perspective.

High School Essay Contest Winners

The Prindle Institute is excited to announce the winners of the first annual High School Ethics Essay Contest! Over 100 high school students responded to the prompt “Should we impose a travel ban on countries with Ebola?” The five winners received a cash prize of $300. Excerpts from the five winning essays are featured below. Continue reading “High School Essay Contest Winners”

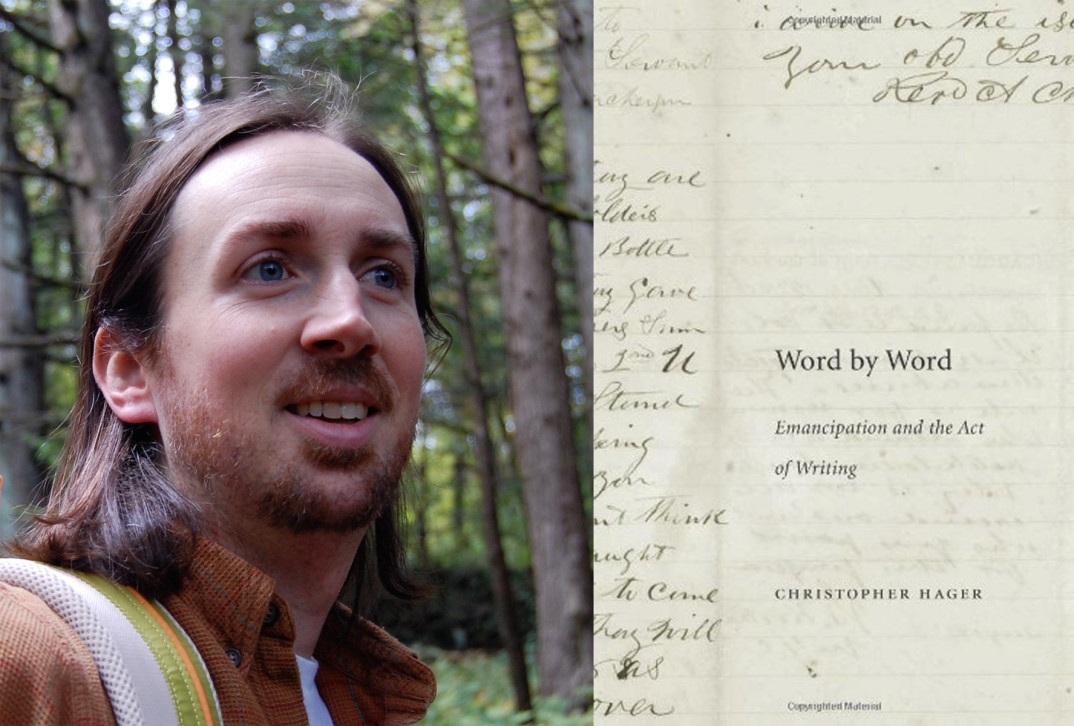

Frederick Douglass Prize Winner will be the 2015-2016 Schaenen Scholar

The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics is proud to announce that Christopher Hager will be the 2015-2016 Nancy Schaenen Endowed Visiting Scholar of Ethics.

Dr. Hager received his bachelor’s degree from Stanford University and his Ph.D. from Northwestern University. Currently he is Associate Professor of English at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, where he teaches courses in American literature and cultural history and, for the past three years, has co-directed the Center for Teaching and Learning. He is the author of Word by Word: Emancipation and the Act of Writing (Harvard Univ. Press, 2013), a study of the writing practices of enslaved and recently emancipated African Americans, which won the Frederick Douglass Prize and was a finalist for the Lincoln Prize. Professor Hager’s research has been supported by fellowships and grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Council of Learned Societies, and the American Philosophical Society, among others.

A scholar of nineteenth-century American literature and history with expertise in slavery and the Civil War, Hager researches the lives and writings of marginally literate people. At the Prindle Institute, he will be considering the ethical problems of historical knowledge, of understanding the past predominantly through the eyes of highly literate people. In addition to teaching in the English department and collaborating with members of the Prindle community, he will be researching the history of illiteracy in the U.S. and working on a book manuscript, “I Remain Yours: Common Lives in Civil War Letters.”

In the fall semester he will teach a course on American Writers (ENG 238). The class will survey American Literature, but as the Schaenen Scholar, Hager will construct the survey in a way that has a focus on moral questions. Students will be encouraged to consider ways that particular ethical problems get addressed by a “constellation of texts over a period of time”.

Hager says, “My working plan is to focus the course on the classic tension between individualist and collectivist impulses in American democracy — to each his own, or e pluribus unum? — and on the migration of ethical concern between individualist (“conscience”) and collective (“reform”) frameworks.”

“I’m thrilled to have Hager joining the team here at Prindle,” said Prindle Director, Andrew Cullison. “His work sheds interesting light on history and literature, but it also speaks to ethical issues related to marginalization and shame in contemporary society. His work also highlights that constructing narratives about the past can have a very serious moral dimension, particularly when you make decisions about which voices to include and which to ignore. It’s going to be great having him around to help facilitate discussions on these topics.”

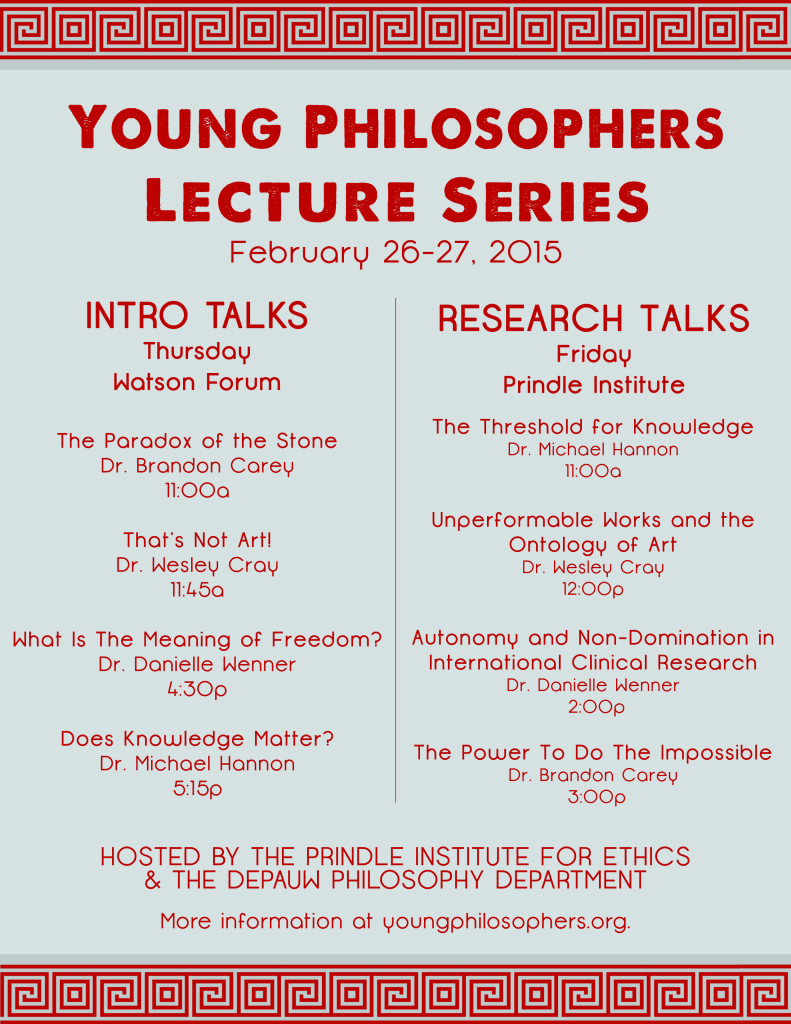

Prindle and DePauw Philosophy Department to host Young Philosophers Lecture Series

On Thursday-Friday, February 26-27, the Prindle Institute and the DePauw Philosophy department will host Young Philosophers Lecture Series. The series was started by Andrew Cullison, Director of the Prindle Institute, in 2008 at SUNY Fredonia. This is the first year that the series will be held at DePauw.

The lecture series brings four recent Ph.D. grads to campus to deliver talks on their philosophical research. This year, the selected participants are Dr.Brandon Carey of Columbia Basin College, Dr. Wesley Cray of Grand Valley State University, Dr. Danielle Wenner of Carnegie Mellon University, and Dr. Micheal Hannon of Fordham University. Each scholar will present one introductory level and one research level lecture. The introductory talks take place Thursday, February 26th in Watson Forum and are geared to those who have little to no philosophy background. The research talks are primarily directed towards other philosophers and experienced philosophy students, however, all are welcome to attend. The research talks will be held on Friday, February 27th in the Prindle Auditorium. One of the objectives of the Young Philosphers Lecture Series is to have something for everyone. This is why both introductory and research level talks are presented.

If you are interested in attending lunch on either day, please fill out this form by February 24.

Additionally, those interested in past Young Philosophers Lectures may visit the Young Philosophers website to view previous presentations. This year’s presentations will be available online shortly following this week’s event.

The Prindle Institute for Ethics and the DePauw Philosophy department are thrilled to be hosting this exciting event. We hope that those in the area, including the DePauw and Greencastle communities as well as those from nearby Indiana colleges, will be able to join us!

Ethics of School Cancellation – Day of Inclusion

With the recent announcement of details regarding DePauw University’s Day of Inclusion activities, some in our community have questioned whether cancellation of school and requirement of attendance is warranted for this large-scale community discussion and day of learning. On DePauw’s intellectually driven campus, it is important to analyze the ethics involved with such a decision, and for us to come together as a community in solidarity. Continue reading “Ethics of School Cancellation – Day of Inclusion”

Decreasing Sexual Assault: Should Sororities Host Parties Too?

Officials at Brown University have ruled that the fraternities Phi Kappa Psi and Sigma Chi “created environments that facilitated sexual misconduct” at fraternity parties. Brown University isn’t the first college where stories of sexual assault at fraternity parties have made national news. There was the situation with the Rolling Stone University of Virgina incident which resulted in a ban on fraternities until January 9. Colombia University student Emma Sulkowicz, famous for carrying her mattress around until her rapist is expelled, attended President Obama’s State of the Union on January 20. With sexual assault being a very real fear for students nationwide, some sororities have decided that they should host their own parties.

Continue reading “Decreasing Sexual Assault: Should Sororities Host Parties Too?”

Buried Without A Brain: Should Shipley’s Family Have Been Informed?

In the news since 2010, the ethical dilemma of Jesse Shipley’s brain has reached headlines once again. The Shipley family discovered their son’s missing organ after a high school field trip to the morgue resulted in students informing the family that Jesse’s brain was in a jar, labeled with his name. Nearly a decade after Shipley’s body was buried without his brain, the court is still weighing in on this ethical dilemma: Should medical examiners have the right to remove (and keep) the organs of the dead?

Continue reading “Buried Without A Brain: Should Shipley’s Family Have Been Informed?”

The Rolling Stone UVA Rape Story Debacle

This post by Dr. Jeff McCall was originally published by The Indy Star on December 26, 2014.

Journalism enters dangerous territory when reporters look to tell “stories” that are more dramatic, more sensational and more confrontational than what is provided by real life. Rolling Stone magazine found this out with its recent, misguided story about sexual assault at the University of Virginia.

Ethics in the Boston Marathon Bombing Trial

The trial of Dzhokar Tsarnaev, one of the alledged bombers from the Boston Marathon Bombing in 2013, will begin today with jury selection. Tsarnev has pleaded not guilty. His lawyers attempted to reach a plea deal with federal prosecutors, but a deal was unable to be made. Tsarnaev could receive the death penalty, and his attorneys tried to make a deal in which the death penalty is off the table if he pleads guilty. Instead, Tsarnaev would have received a life sentence without parole. The Justice Department has been resistant to removing the option of a death penalty, and Attorney General Eric Holder approved the request to pursue the death penalty. Although Holder is usually against the death penalty, he has said that the heinous nature of Tsarnaev’s crimes and Tsarnaev’s lack of remorse warranted his authorization. The death penalty was ruled unconstitutional in 1982 in Massachusetts, but federal cases in the state may still pursue the death penalty.

Striking a plea deal would have prevented a trial; a trial of this magnitude could take months. No trial means that less money will be spent on Tsarnaev’s case, and prevent emotional pain to survivors and victims’ families. Emotional distress of survivors and victims’ families has been a topic of discussion with this case before, as prosecutors attempted to prevent Tsarnaev from being able to view autopsy photos of victims, saying that it would cause pain to survivors. A judge denied this request. Victims’ families and survivors were warned in December that the evidence for the trial was going to be gruesome and may be difficult to handle. Some survivors have said that they will testify, if summoned. Others simply want to avoid the whole situation. The trial is taking place in Boston; the defense has argued that this makes it nearly impossible to seat a fair jury since the city was so strongly impacted by the bombing. Jury selection has begun in Boston, however, and the trial itself is tentatively set to begin on January 26.

Should the Justice Department continue to pursue the death penalty, especially in a state where it has been ruled unconstitutional? Is it ethical to have survivors and their families relive the events graphically? Should emotional distress be taken into account in trials at all? Is it ethical to hold a high-profile trial in the city where it happened, both from the standpoint of causing emotional pain to others and from the standpoint of the accused being able to have an impartial jury?

Consumerism, Capitalism, and Personal Identity

Shopping hangovers are just as real of a threat at this time of year as the drinking ones. With Black Friday and Cyber Monday just behind us (but Christmas still ahead), it can seem once again like everyone’s busy typing denouncements of consumerism with one hand while grabbing sweet deals and swiping plastic with the other. Amidst the holidays, we are sure to continue to hear complaints that the season has been ruined by a focus on material possessions and rampant “consumerism.”

Few would deny that the western world does exist today in a state of “consumer culture.” By many accounts, capitalism is its cause. Though “consumerism” also refers to political efforts to support consumers’ interests, the term has come to bear a rather pejorative connotation referring to the prominence of consumptive activities in everyday life, especially insofar as consumptive activities seem to be escalating for individuals and societies at an unsustainable rate.

Criticisms of consumerism take several forms, of varying plausibility. Sometimes, critics suggest that people harm themselves in placing too much importance on material possessions. Other critics worry that consumerism destroys the potential for genuine individuality, as through the spread of homogenous mass market products. Au contraire, perhaps consumerism instead fosters individuality, but of a pernicious and illusory sort. Or perhaps the means – and not the ends – of consumerism are morally problematic, insofar as this social state has been brought about through psychological manipulation by advertisers.

Defenders of a basically capitalist order must bite several bullets in the interest of intellectual honesty. It’s true that not all purchases make consumers meaningfully better off. Indeed, the challenge of facing too many choices is a well-known psychological phenomenon. Sometimes people find their behaviors unduly shaped by external sources, and marketing can be amongst them. Expressing individuality (as through consumption) is of dubious moral value when doing so seems to make people isolated and self-absorbed instead of happier.

But what is the alternative? If adults don’t or shouldn’t derive their identities from autonomous personal activities – many of which are consumptive – from where exactly are they supposed to derive them? Liberal progressives (including those of an anti-capitalist bent) also worry about citizens’ identities being shaped too heavily by their arbitrary family circumstances, their race or ethnicity, their religions, and their work lives. But figuring out who we are is an essential feature of the “human condition,” and alleviating one kind of external pressure just makes room for the others to flood in.

Buying things really does often help us to form our mature selves: the way you dress, the way you decorate your home, and the range of your hobbies express a nascent identity, allow you to take it for a test drive, and provide pathways for changing it in a kind of ongoing identity feedback loop. And buying experiences (instead of stuff) shapes humans lives even better yet: restaurant expenditures aren’t just food, they fuel social gatherings. Vacations aren’t just plane tickets, they’re memories to anticipate and then treasure.

And, through a supply-and-demand lens, notice that you can only have it one way or another: when the prices for things go down, people want more of them. It’s implausible to imagine any world in which consumer goods become cheaper (and therefore more widely and equitably available) but ordinary humans don’t buy more at the margin. It signals one’s higher social status to look down on those people waiting in an hours-long Walmart line for cheap televisions and computers, but there’s certainly nothing inherently wrong with taking advantage of deals to get things for your family that would otherwise be financially out of reach.

Capitalism may be the cause of consumer culture, but consumerism is only partially a problem – and, to that extent, capitalism can also provide the solution. When people are generally rich in historical terms, we can afford (figuratively and literally) to spend time criticizing the ways in which they spend their money. Self-help and self-improvement have captured philosophical interest since ancient times, but the circumstances within which we conduct these activities are historically contingent. Navigating the prosperity of a post-industrial world requires consumer habits that can be learned and practiced as part of a balanced life. Though happiness will never be handed to us on a silver platter (or in a shopping bag), we should be glad to find ourselves operating so close to the top of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Is Envy Always Malicious? (Part Two)

This post originally appeared on December 4, 2014.

When I was 8, I started ballet. I was a disciplined kid who took everything seriously, and dance quickly became a great passion of mine. But for many years I wasn’t that good; I felt I lacked the natural physical abilities that bless talented ballerinas.

One day something changed. I was observing the course immediately after mine. In the center of the studio, Laura, the first in her class, was performing a step in which one leg is elevated above 90 degrees. She was very similar to me in many respects, rich in determination but lacking in natural talent, her legs and feet modeled only by hours of obstinate exercise. Her leg was so much higher than mine had ever been! She looked fierce and strong, and I wished I could be like that. But beneath her smiling face, I could see the strain: she was sweating a lot, and her leg was shaking slightly. I felt a complex, painful emotion. I was ashamed both of my inferiority and of minding it so intensely. At the same time, I was inspired and determined to work harder: if she could do that, so could I! I kept dancing, with renewed enthusiasm, and by the time I graduated from my dance school I, too, was the best in my class.

I believe that what I felt that day toward my peer was what we can call emulative envy. It is a kind of non-malicious envy that has two fundamental characteristics. First, it is more focused on the lacked good, rather than on the fact that the envied has it. In my case, I was more bothered by my lack of excellence than by the fact that Laura was excellent. Therefore, this kind of envy has an inspirational quality, rather than an adversarial one. The envied appears to the envier more like a model to reach, or a target to aim to, than a rival to beat, or a target at which to shoot. When the envier is, vice versa, more bothered by the fact that the envied is better than them, than by the lack of the good, the envied is looked at with hostility and malice, and the envier is inclined to take the good away from them.

Second, emulative envy is hopeful: it involves the perception that the envier can close the gap with the envied. When this optimism about one’s chances is lacking, being focused on the good is insufficient to feel emulative envy, because we don’t believe in our capability to emulate the envier. Thus, we may fall prey of what I call inert envy, an unproductive version of emulative envy in which the agent is stuck in desiring something she can’t have, a dangerous state that can lead to develop more malicious forms of envy. In Dorothy Sayers’s vivid metaphor: “Envy is the great leveler: if it cannot level things up, it will level them down” (Sayers 1999).

There are two possible ways of leveling down: in what I call aggressive envy, the envier is confident that she can “steal” the good. Think about a ballerina who secures another dancer’s role not by her own merit but via other means, such as spreading a rumor about that dancer’s lack of confidence on stage. But this kind of “leveling down” is not always possible, or at any rate does not appear possible to the envier. In such a case, the envier is likely to feel spiteful envy, as it may have been in Iago’s case: he could not take away the good fortune Othello had, but he was certainly able to spoil all of it.

Spiteful, aggressive and inert envy are all bad in one way or another, but emulative envy seems void of any badness. Here I cannot detail the ways in which it is different from the other three, but I’d like to conclude this post with one very interesting feature it possesses. Empirical evidence (van de Ven et al 2011) shows that emulative envy spurs one to self-improve more efficiently than its more respectable cousin: admiration. This result is less surprising once we think that admiration is a pleasant state of contentment, and thus is unlikely to move the agent to do much at all. As Kierkegaard aptly put it: “Admiration is happy self-surrender; envy is unhappy self-assertion” (Kierkegaard 1941).

References

Kierkegaard, S. 1941, The Sickness Unto Death: A Christian Psychological Exposition For Upbuilding And Awakening (1849), New York: Oxford University Press.

Sayers, D. 1999, Creed or Chaos? Why Christians Must Choose Either Dogma or Disaster (Or, Why It Really Does Matter What You Believe), Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute Press.

van de Ven N., Zeelenberg M., Pieters R. 2011, “Why Envy Outperforms Admiration,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(6): 784–795.

How Not to Defend Voter Restriction Laws

I was listening to this NPR story today that presented two rebuttals to the claim that voter restriction laws make it difficult for historically disenfranchised people to vote. They both strike me as bad rebuttals, and I’d like to consider them in turn. (You can listen to the story above).

The first is that it claimed that activists against voter restriction may be hindering their own cause by helping people vote. Pam Fessler claimed that as activists succeed in getting people what they need to vote, they provide evidence that these laws are not that harmful – that they don’t stop qualified voters from voting. That’s such an odd position to take. In any case where someone succeeds in helping someone overcome an obstacle, it’s not evidence that there was no obstacle. Suppose we removed all accessibility ramps from all of the town courthouses. Suppose outraged activists stood by some of the courthouses and helped lift people in wheelchairs up the steps. It would be silly to say that these activists have provided evidence that removal of the ramps is not harmful. It’s still true that a vast majority of people without the assistance of someone would not access the courthouse, and that they would have to do more than your average person to access the courthouse. The same seems true of voter restriction laws; many people must jump through burdensome hoops

Second, it is argued that because black voters in Georgia out voted white voters (by percentage) in the last general election, the voter restriction laws do not harm black voters. This does nothing, what-so-ever, to show that voter ID laws haven’t made it more difficult for black voters. The relevant statistic would be whether the percentage of black voters has decreased in recent years, and there is actually some evidence to suggest that it has. Approximate 1,329,000 black people voted in the 2008 general election. Approximately 1,280,000 voted in the 2012 general election. That’s a decrease in black voters. If the population of black voters remained constant or increased (which is likely), it’s a decrease in the percentage of black people voting in the state of Georgia.

You can accept everything I’ve said here, and still be in favor of voter restriction laws. My point is simply that this is not the way to defend voter restriction laws.

Announcing the Prindle Institute High School Essay Contest

I am very happy to announce the beginning of the annual Prindle Institute High School Essay Contest. Each year, the Prindle Institute will award high school students for the best essays on a topic of ethical concern. This year, we will award five (5) high school students $300 each for the best essays on this year’s topic.

This year’s topic is Ebola. The question we would like high school students to consider is whether the United States should impose a travel ban to and/or from regions that have been inflicted with an outbreak of the Ebola virus.

Complete details are available at the Prindle Institute High School Essay Contest Page. Students can submit their essays using the online submission form at the contest page.

We look forward to reading your submissions.

A Libertarian Argument for Public Education

A recent Gallup poll found that 70% of Americans favor using federal money to expand pre-school programs across the country. There were differences along party lines. Only 53% of Republicans favor the expansion, while 87% of Democrats favor the expansion.

To some extent, this disparity is unsurprising. Fans of small government typically concede that government should tax for the purposes of a minimal police state. We need the police to protect liberty at home. We need the courts to enforce contracts and protect people against fraud. We need the military to protect our liberty from aggressive foreign states. All of this is justified by the libertarian ideal that governments may tax in order to protect liberty and freedom. Taxation encroaches on liberty, but if the tax is to secure greater liberty and freedom, then it is okay for libertarians and conservatives.

Typically, this libertarian ideal is thought to exclude funding for other programs that aren’t for securing liberty such as welfare, health insurance, scientific research, public works, postal service, and public roads. If people really want those things, the free market will find a way to make it so. The libertarian ethos is also typically thought to exclude public funding for public education. It’s this latter thought, that I want to challenge here. I think libertarians, on libertarian grounds, ought to strongly favor public funding for high quality education for all.

A well-educated America would be populated with people who are not as susceptible to fraudulent assaults on their liberty. A well-educated America would be populated with people who could spot attempts to deprive other citizens of liberty. A well-educated America would be populated with people who would creatively address, perhaps even via the private sector, assaults on liberty.

Libertarians think we can permissibly invest in soldiers and police because they are an effective insurance against encroachments on liberty. Why not think of every citizen as a potential defender of liberty? Investing in quality education for every citizen is excellent insurance against fraud and violation of freedom and liberty, which is at the top of the libertarian/conservative list for things a government can tax to provide.

You might argue that our current system of education is broken. It’s a mess, you might say. Funding it is an inefficient means to ensure quality education for all students. However, that’s not an argument for not funding education. At best, it’s an argument for transforming our public education model. If we have planes that aren’t that good, we use them to defend our country while we build better planes. We don’t abolish the Air Force.

You might worry that as we transform citizens into defenders of liberty, we also educate better criminals and better con-artists. However, this is a risk that we take training soldiers and police, and they do sometimes use their skills to violate people’s liberty. But we don’t cut funding for the military and the police simply because we realize that in training potential heroes we also train potential menaces. The solution here is programming that is designed to mitigate the number of potential menaces and the degree to which they can inflict harm.

The bottom line is that education is not just about individuals securing better lives for themselves. If it were, then it would make sense (by libertarian principles) that people should pay for it if they want it. Education is a route to the kind of public good that is central to what a libertarian (typically) thinks we can tax for. It is an effective means to stabilizing our democracy and ensuring that we have vigilant footsoldiers everywhere who will defend precisely the thing that a libertarian thinks the government can pay to defend – our freedom. If you ascribe to libertarian ideals, you should support funding for education.

Conflict Kitchen will be hosted Oct. 27-30 by Prindle, Conflict Studies and the Art Department

The Conflict Studies Program, The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics, and the Department of Art and Art History are thrilled to announce an upcoming visit by artists Jon Rubin and Dawn Weleski, and chef Robert Sayre, of Conflict Kitchen.

We will welcome them to campus the week immediately following fall break. Public events include:

Public Lecture by Dawn Weleski and John Rubin, founders of Conflict Kitchen

Monday, October 27 at 4:15 PM

Peeler Art Center, Auditorium

Free and open to the public

Meal at the Prindle Institute

Thursday, October 30 at 6 PM

Prindle Institute, Great Room

Open to the public. Tickets $15 ($9 for DePauw students)

Tickets go on sale Wednesday, October 15 and are available for purchase at the front desk of Peeler Art Center Monday thru Friday 10 AM-4 PM

Conflict Kitchen is an art project that takes shape as a restaurant in Pittsburgh that “only serves food from countries in which the United States is in conflict,” with the country of focus changing every few months. The restaurant is currently in its Palestinian phase, and past versions include Venezuela, Afghanistan, North Korea, Cuba, and Iran.

Using strategies of socially and publicly engaged art, Conflict Kitchen places an equal amount of emphasis on preparing authentic meals as they do on educating customers on the conflict of focus. Not only do they visit the countries to gain a greater understanding of the conflict and cuisine, but they also interview Pittsburgh residents from these nations to better understand different perspectives. The food at Conflict Kitchen is served in paper wrappers that function as informative handouts with direct quotes from these personal interviews as well as information about the cuisine, politics, and culture of the country.

Artists Dawn Weleski and John Rubin, the creative founders of Conflict Kitchen, will present a public lecture on Monday, October 27 at 4:15 PM in Peeler Auditorium. While on campus, they will also visit several classes, meet with students and faculty, and conduct art critiques with Studio Art majors.

On Thursday, October 30 at 6 PM, Dawn Weleski and Robert Sayre, the chef at Conflict Kitchen, will serve a Palestinian meal at Prindle and give a presentation about the politics of food in Palestine and the way it is used to establish cultural identity. A limited number of tickets to this event will be available on October 14 to DePauw students, faculty, staff, and Greencastle community members.

We hope you will consider attending the Conflict Kitchen lecture and meal to learn more about this unique restaurant, social practice art, and the conflict in Palestine.

Director Interview with D3TV

Thanks to the D3TV crew for having me on their news show last night, and thanks for posting the clip of my interview. Here’s the interview. In it, I discuss some goals for the Prindle Institute. I talk about two of our new programs, the Prindle Prize program and the Prindle Post. I also discuss what we’re doing to address some challenges for the Institute.

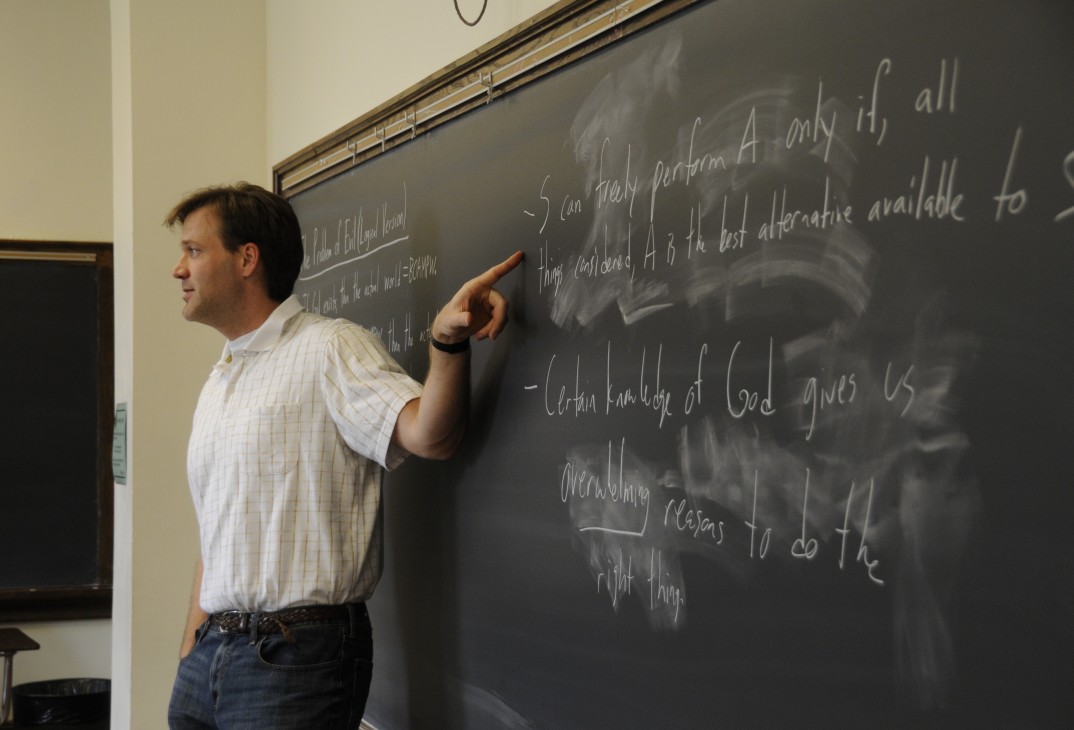

Can moral laws exist without God? A brief introduction to “Robust Ethics”

Last week we published the abstract of Erik Wielenberg’s new book, Robust Ethics: The Metaphysics and Epistemology of Godless Normative Realism. In this guest post, Wielenberg, Professor of Philosophy at DePauw University, follows up with a more in-depth discussion of the book and some of the philosophers that have influenced his thinking on moral realism and God’s existence.

In 1977, two events that would significantly impact my life took place. First, the film Star Wars was released. Second, two prominent philosophers, J.L. Mackie and Gilbert Harman, unleashed some influential arguments against moral realism. My book is about the second of these two events.

In his famous argument from queerness, Mackie listed various respects in which objective values, if they existed, would be “queer.” Mackie took the apparent queerness of such values to be evidence against their existence. One feature of objective values that he found to be particularly queer was the alleged connection between a thing’s objective moral qualities and its natural features: “What is the connection between the natural fact that an action is a piece of deliberate cruelty — say, causing pain just for fun — and the moral fact that it is wrong? … The wrongness must somehow be ‘consequential’ or ‘supervenient’; it is wrong because it is a piece of deliberate cruelty. But just what in the world is signified by this ‘because’?” (1977, 41) Mackie was also dubious of the view that we could come to have knowledge of the objective moral qualities of things. He wrote that friends of objective moral values must in the end lamely posit “a special sort of intuition” that gives us knowledge of objective values.

Harman, for his part, noted an apparent contrast between ethics and science. He compared a case in which a physicist observes a vapor trail in a cloud chamber and forms the belief “there goes a proton” with a case in which you observe some hoodlums setting a cat on fire and form the belief “what they’re doing is wrong” (1977, 4-6). Harman was happy to classify both of these as cases of observation (scientific observation and moral observation respectively), but he noted that the moral features of things, supposing that they exist at all, seem to be causally inert, unlike the physical features of things. Harman thought that this feature of moral properties suggests that we ought to take seriously the possible truth of nihilism, the view that no moral properties are instantiated (1977, 23). But others have drawn on Harman’s premise to support not nihilism but rather moral skepticism, the view that we do not (and perhaps cannot) possess moral knowledge. It is the latter kind of argument that I discuss in my book.

Some have suggested that theism provides the resources to answer these challenges. Mackie himself, although an atheist, suggested that theism might be able to answer his worries about the queerness of the alleged supervenience relation between moral and natural properties. In his 1982 book The Miracle of Theism, he suggested that “objective intrinsically prescriptive features, supervening upon natural ones, constitute so odd a cluster of qualities and relations that they are most unlikely to have arisen in the ordinary course of events, without an all-powerful God to create them” (1982, 115-6). More recently, Christian philosopher Robert Adams suggests that the epistemological worries that arise from Harman’s contrast between science and ethics can be put to rest by bringing God into the picture (Adams 1999, 62-70).

Thus, an interesting dialectic presents itself. Mackie and Harman, who do not believe that God exists, see their arguments as posing serious challenges for moral realism. Some theistic philosophers argue this way: if we suppose that God does exist, then we can answer these challenges to moral realism. Without God, these challenges cannot be answered. Since moral realism is a plausible view, the fact that we can answer such challenges only by positing the existence of God gives us reason to believe that God exists.

I accept moral realism yet I believe that God does not exist. I also find it unsatisfying, perhaps even “lame” as Mackie would have it, to posit mysterious, quasi-mystical cognitive faculties that are somehow able to make contact with causally inert moral features of the world and provide us with knowledge of them. The central goal of my book is to defend the plausibility of a robust brand of moral realism without appealing to God or any weird cognitive faculties.

A lot has happened since 1977. A number of increasingly mediocre sequels and prequels to the original Star Wars have been released; disco, mercifully, has died. But there have also been some important developments in philosophy and psychology that bear on the arguments of Mackie and Harman sketched above. In philosophy, the brand of moral realism criticized by Mackie has found new life. In psychology, there has been a flurry of empirical investigation into the nature of the cognitive processes that generate human moral beliefs, emotions, and actions. As a result of these developments the challenges from Mackie and Harman sketched above can be given better answers than they have received so far — without appealing to God or weird cognitive faculties. That, at any rate, is what I attempt to do in my book. In short, my aim is to defend a robust approach to ethics (without appealing to God or weird cognitive faculties) by developing positive accounts of the nature of moral facts and knowledge and by defending these accounts against challenging objections.

Works Cited

Adams, Robert. 1999. Finite and Infinite Goods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harman, Gilbert. 1977. The Nature of Morality: An Introduction to Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mackie, J.L. 1977. Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong. New York: Penguin.

Mackie, J.L. 1982. The Miracle of Theism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Will climate divestment work?

Scott Wisor recently wrote a post titled “Why Climate Change Divestment Will Not Work” over at the blog for the journal Ethics & International Affairs (EIA). The post is quite provocative. Visit the EIA blog, here, to read it.

Wisor presents himself as convinced that climate change is happening, poses a grave threat, and makes ethical demands on us all. Nevertheless, as his title suggests, he believes that one prominent strategy for generating mass action on climate change is destined for failure: the movement – led by Bill McKibben and his 350.org – to get large universities and investment funds to divest from fossil fuel companies. If fossil-fuel divestment efforts are doomed to fail, then McKibben’s movement functions as a costly distraction from our pressing ethical obligation not just to act but to act effectively. As Wisor puts it, “why spend half a decade or more on a tactic that at best won’t make a difference? Why not direct attention to the more urgent and effective task of placing a price on carbon?”

I have a number of responses to Wisor’s specific arguments, but in this post I’d like to offer two more general reflections aimed at tempering his conclusions. The line of criticism I’ll be pursuing in this post is an odd one – that Wisor’s arguments and conclusions are all too plausible. More specifically, his argumentative target is ill-defined and appears too easily established. When looked at more closely, the real difficulties movements face in achieving success also require more nuanced arguments that a particular movement will fail.

My first point begins by noting that a sober look at the evidence certainly suggests that Wisor’s conclusion is likely to be true. Pick any successful social movement from the past – the civil rights movement, the movement for India’s independence from England, etc. Scholars of social change frequently note that while those movements were in process the odds seemed stacked against them. Moreover, even movements we know (with hindsight) to have been successful seemed destined to fail almost right up until they managed – somehow – to succeed. Indeed, all large scale and eventually successful movements for social change have faced armies of naysayers claiming that the tactics they employed (e.g., non-violent resistance in the cases I’ve mentioned) would not work and that those movements’ efforts served as distractions from other, allegedly more effective measures that people genuinely devoted to the cause should be supporting instead. Perhaps the most eloquent response to this kind of criticism comes in Martin Luther King Jr.’s justly famous “Letter from the Birmingham Jail.” We’re on your side, his critics said, but your tactics are wrong and will backfire.

Antonio Gramsci made a similar point in saying, “I’m a pessimist because of intellect, but an optimist because of will.” The idea in Gramsci’s quote is that rational reflection on the odds of social change will almost always result in a thoroughly justified pessimism. If you’re aware of the obstacles and think about the circumstances carefully you’re sure to come up with a thousand reasons why social change just doesn’t stand a chance. Gramsci acknowledges that effective advocates for social change need to face up to this grim fact. They need the “pessimism of the intellect” so that they know what they’re up against – without this they will be ineffective idealists tilting at windmills. But social change movements do sometimes succeed, and without the benefit of hindsight it’s extremely difficult to tell which movement, if any, is going to pull off a major victory. And that means that people devoted to the hard work of social change need more than just the pessimism that comes from clear-sightedness of the long odds we face. They also need the “optimism of the will,” the willingness to work against long odds with the hope and confidence that some apparently doomed strategy will eventually succeed. To quote Margaret Mead, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed, citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.” Without the benefit of hindsight, a strong case can be made that all social movements are doomed to failure, and if that is all Wisor is arguing in the case of the fossil fuel divestment movement then his arguments are both unsurprising and should be of little interest to committed and thoughtful activists. If Wisor is arguing for an interesting claim, it must be not just that we’re justifiably pessimistic about the divestment movement’s odds of success. He must argue for the stronger claim that the movement is actually tilting at windmills, that it is so clearly out of line with reality that it should be viewed as a waste of time even by those with intimate knowledge of the challenges all social movements face.

My second response to Wisor’s argument is generated by asking a simple question: when can we say that a movement has succeeded, that its efforts have “worked”? Wisor’s blog post seems to imply a very demanding standard for movement success – a movement must solve the problem it’s designed to address (in this case climate change). And if this is what success requires then once again Wisor is arguing for a conclusion that is simply too easy. It is widely acknowledged that there are no silver bullets with regard to large problems like this, and in the case of climate change it is also widely acknowledged that it’s too late to “solve” the problem anyway: what we’ve already done commits us to enough warming that dangerous impacts are already unavoidable. Of course, that doesn’t mean we can’t still succeed in mitigating climate change and heading off even more catastrophic impacts, but no one heading up the fossil fuel divestment movement is under the illusion that their efforts will “solve” the problem in this sense.

Still, this isn’t the only metric for success. Activists often view movement success not in these all-or-nothing terms but as, instead, accruing piecemeal, slowly, and building over time. A social movement that doesn’t “solve” its intended problem in the first sense may nevertheless raise awareness (and so make future solutions easier to institute). Movements may build networks of effective and motivated actors (who may work better together in the future because of their present experience). They may convert major institutions and groups to take stands that they otherwise would not have taken (and so, again, make future change more likely). And so on.

All of these things plausibly constitute social movements succeeding, but none of Wisor’s specific arguments for why the fossil fuel divestment strategy “will not work” undermine the idea that the movement has already succeeded – that it has “worked” far beyond the dreams of most movements. According to a report by Arabela Advisors, “181 institutions and local governments and 656 individuals representing over $50 billion dollars have pledged to divest to-date.” Think too of the marches, meetings, media attention, position papers, etc. the movement has generated, and what they mean for better advocacy for policies of all sorts in the future. The point is just that by reasonable standards the divestment movement is already a success, and nothing in Wisor’s piece suggests this movement (and others) can’t build (piecemeal, and bit by bit) on their successes in the future.

Moreover, it is important to note that when Wisor suggests alternative efforts that he thinks stand a greater chance of succeeding he mentions only a “price on carbon” and unspecified “regulatory efforts” to combat climate change. The problem here is that Wisor’s suggested solutions do not constitute ideas for building a movement. To generate a movement you need to mobilize masses of people and institutions and organize them around applying political pressure for change. Of course we should put a price on carbon – but how exactly does Wisor propose that we build the political movement to get that done? When Wisor has an idea for building a powerful movement around putting a price on carbon (or his favorite regulations) and he can show, further, that his new strategy is likely to generate more traction, enthusiasm, and support from grassroots activists and major institutions than the divestment movement has already succeeded in generating then will he have a strong real case for saying that there are more effective strategies we should be pursuing. Saying simply that we should put a price on carbon isn’t even in the same ballpark as building the movement to divest from fossil fuels, however. McKibben’s fossil fuel divestment strategy may not be a silver bullet guaranteed to succeed (no social movement in history ever has been, of course), but it has been a concrete and already effective strategy for bringing together a new, strong, and powerful coalition on climate.

I realize that my fairly general criticisms of Wisor’s post don’t address the specifics of his arguments. For all I’ve said here it remains possible that his specific objections to the fossil fuel divestment movement’s strategies are indeed damning. That is, I have not argued that the fossil fuel divestment movement is not tilting at windmills in a way that anyone who cares about climate action should shun, nor have I argued that it is only beset by the perfectly ordinary sort of “pessimism of the intellect” that beset all social movements (even ones that have succeeded). Still, I hope I’ve clarified the way in which Wisor’s argument seems to aim at a conclusion that is both too easy and too unsurprising. If his arguments are to be of service to his claimed allies in the incipient climate movement they will need to show more than just that there are good reasons for pessimism. He’ll need to show that the divestment movement tilts at windmills. With regard to the former task Wisor’s arguments (unsurprisingly) succeed. With regard to the latter task I’m much less sure.

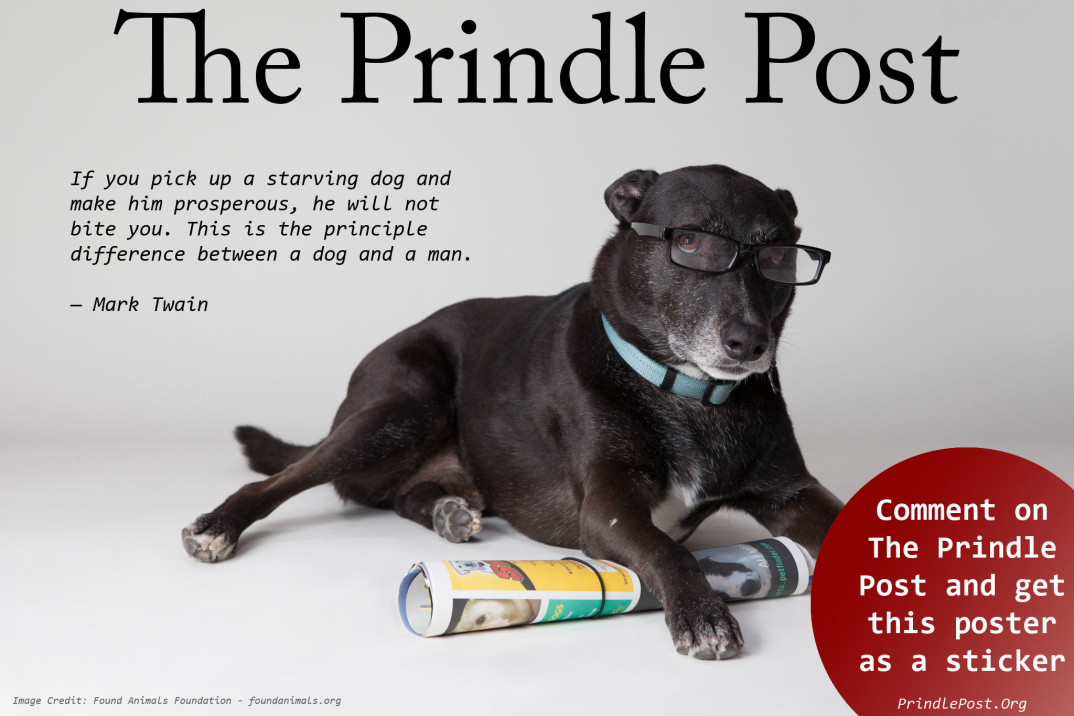

Want a Prindle pup sticker?

Comment on a Prindle Post article and we’ll send you a free sticker of this image featuring Rio, who’s become something of a mascot for the Prindle Post as of lately. Here are some very brief ground rules:

General Guidelines

1. The comment has to engage with the post content in some way.

2. The comment cannot be on this particular post. You may comment on this post if you want (of course), but it won’t get you a stick. You must engage the ethical discussion in some way.

DePauw Community

If you comment and provide your DePauw email address through Gmail or a Prindle Post account, we’ll send the sticker to your campus address. Remember: commenting on Prindle Post articles makes you eligible for the Prindle Post Top Commenter Prize – worth $150.

Not from DePauw?

After you comment, send us a self-addressed stamped envelope to:

Andrew Cullison

The Prindle Institute

DePauw University

P.O. Box 37

Greencastle, IN

We’ll send the sticker your way.

Happy commenting!

What the Ray Rice Video Suggests About Our Moral Thinking

At 1:00 AM on September 8 TMZ posted a disturbing security video showing Ray Rice, formerly of the Baltimore Ravens, punching his then-fiancée, Janay Palmer, rendering her unconscious. At 11:18 AM the Ravens tweeted that Rice’s contract had been terminated. At 11:41 AM, the NFL tweeted that Rice had been suspended from the league indefinitely.

Here’s at least one odd thing about this: it was already known that Rice punched Palmer and rendered her unconscious. As early as February 2014 there were reports of what the video depicted. So, why the outrage now? Why the sudden calls for action? After all, nothing morally relevant is changed by the fact that now many people have seen the punch rather than merely having been told about it.

Perhaps you’re like me, though. Although there were reports of the incident in February 2014, you weren’t aware of the incident until now. There’s nothing about seeing the incident that changes its moral features, you might say, it’s just that the video gave the story a wider reach and now you’re aware of it. This, in turn, increased the pressure on the Ravens and the NFL to take action.

That’s perhaps a comforting thought, at least with respect to our reaction to the case (it’s not so comforting a thought with respect to the Ravens and the NFL). But it masks a thought that is less comfortable, even for you and me. The less comfortable thought is that even if you or I had known about the incident in February, we still probably wouldn’t have responded in the same way as we did after seeing the video. Why? Because there is considerable psychological evidence that our moral responses to cases are strongly influenced by our emotions. [1. For a nice, accessible, summary of some of this research, see Joshua Greene’s 2013 book, Moral Tribes (Penguin Press) His website includes additional papers on the same topic] And—for most of us anyway—seeing a video of domestic violence is much more emotionally engaging than reading a dry report of the same thing.

This should give us pause. Sure, suffering might feel worse if we see it, but does it really make it worse? It seems not. A seen punch hurts just as much as an unseen one; a child that we see starving suffers just as much as one that we do not see. There’s an important lesson here: our moral psychology can sometimes fool us into making spurious distinctions. Our proximity to suffering or way of learning about suffering is not plausibly a morally relevant feature of it, but we often treat it as if it is.[2. This is not a new point. In his 1972 paper, “Famine, Affluence, and Morality”, Peter Singer writes: “The fact that a person is physically near to us, so that we have personal contact with him, may make it more likely that we shall assist him, but this does not show that we ought to help him rather than another who happens to be further away.” (p. 232).] This can have profound consequences, not just with respect to domestic violence in the NFL, but with respect to us playing our appropriate moral role in the world.

Ferguson and Net Neutrality

The shooting of Michael Brown and the unrest in Ferguson raises a host of obvious ethical issues. One that isn’t so obvious is that it highlights the potential importance of knowing about net neutrality and algorithmic filtering. As Zeynup Terfecki has recently argued, what happened in Ferguson is a way to illustrate how net neutrality may be a human rights issue.

Let’s get clear about both terms first. “Net Neutrality” is the thesis that internet service providers should be neutral and enable access to all content and websites available on the internet. Furthermore, they should not favor, speed-up, block, or slow-down content and services from any website. Proponents of net neutrality hold that internet service providers should not be permitted to privilege content from websites and permit them to access a fast lane. Service providers also should not be allowed to intentionally slow down access to content from websites.

If you agree with those sentiments, then you are a fan of net neutrality. If, however, you think a company like Verizon should be able to reach an agreement with ESPN and let ESPN deliver streaming content more quickly to Verizon users, then you favor what I will call a “Tiered Internet.” I won’t go into the pros and cons of net neutrality here, but if you’re interested this Wikipedia entry has a nice summary of the arguments for and against net neutrality.

Now let’s talk about algorithmic filtering. Algorithmic filtering is simply a process by which computer programs instruct computers (via an algorithm) to scan a large amount of information and pull out the bits they are interested in. It has a ton of very useful applications, but we’re interested in how it can be used in the internet service industry. Algorithmic filtering is one of the things that differentiates Facebook from Twitter. Facebook carefully curates what shows up in your feed based on a secret algorithm that (in theory) will prioritize content that Facebook wants you to see. Twitter doesn’t do this. With Twitter you see an unfiltered stream of the tweets of everyone you follow in chronological order.

Terfecki noticed something odd about this difference. Her Twitter feed was loaded with tweets about Ferguson, but when she switched over to Facebook she saw nothing. Facebook’s filtering had managed to bury anything about Ferguson. No one is accusing Facebook of intentionally suppressing Ferguson posts, it’s just that for some reason Facebook’s algorithm prioritized things in such a way that Ferguson posts (for Terfecki) didn’t make the cut. Ferguson posts likely made the cut for many people. So the lesson is, algorithmic filtering has the potential to unintentionally hide important stuff from you that you care deeply about, as it did in Terfecki’s case.

However, there is another important lesson to be learned here, and this is Terfecki’s primary point. What Terfecki wants us to do is take a step back and think carefully about net neutrality. Why? Because tiered internet uses algorithmic filtering. If Verizon wants to prioritize ESPN content, it needs to write a program that automatically filters through everything streaming across its networks, flag content coming from ESPN, and route it to the fast lane.

Why should this have us concerned? Because the way in which service providers could filter and prioritize content are only limited by a programmer’s imagination. Internet Service Providers could, for example, get into the PR business. Are you planning on running for Governor? Do you want that embarrassing story about you from your time at college to go away? Service providers could charge a premium to speed up content from some sites that sing your praises and slow down content from sites that talk about your college days (assuming those sites haven’t outbid you), and voilà – the public is blissfully unaware of your past misdeeds.

The possibility of a truly informed citizenry would be further threatened if news media conglomerates got in the service provider game. News companies (with an agenda) could suppress stories from competing news organizations or media watch-dog websites and drastically shape the political message the country is getting. This is why we need to have a serious conversation about net neutrality. It’s not just about people who want to download large files without being throttled. It’s not just about delivering people free ESPN content quickly, if ESPN is willing to foot the bill. It is, as Terfecki notes, a human rights issue about ensuring that everyone has an opportunity to be a meaningful and well-informed participant in the political process.

Events like the Michael Brown shooting occurred all of the time in the pre-internet era, and the public was simply unaware of it. The internet changed that. Events that we should all be talking about are coming to light for everyone in the country at the same time almost the instant they happen, but we now have the technology to change that. We are rapidly approaching a future where the next Ferguson could happen, and a vast majority of us will be clueless.

More Thoughts on Designing Addictive Video Games

A few weeks ago, Brian Crecente asked me to comment on whether or not I thought video game designers had a moral obligation to think about how they design games in light of recent evidence that some video games seem to be addictive. You can read the full article here, but here’s what I said:

I do think game developers have a moral obligation to think about their game design in light of recent evidence we have concerning the addictiveness, he said. It’s easy to dismiss abuse of a product as a personal choice of the consumer, but as evidence of addiction for any product grows — it becomes less clear how much choice is involved.

What’s more troubling about this phenomenon, is that the business model for games has changed in two important ways that make it very tempting for developers to try and create a game that is addictive. In-app purchase and subscription-based models are more lucrative if the consumer can’t stop playing, as are free games that rely on cost-per-click advertisements. You only make money off your users if they keep coming back to play, and the more addicted they are to the game, the more likely you are to make money off their clicks…Making an addictive game is the obvious choice for maximizing revenue in these new ways….so, I’m worried that we’ll not see developers shy away from actively trying to create addictive games.

That article generated some interesting discussion, and there were three objections that seemed to come up more than once. I thought I’d say something about those three objections. Here they are, followed by my replies.

Objection one: If you think there is something wrong with designing addictive video games, then you must think there is something wrong with developing any kind of product that people become compulsive about. People play golf more than they should. People drink soda more than they should. Are golf ball manufacturers and soft drink companies doing something wrong?

Reply: My short answer to the last question is, “No, I don’t think merely manufacturing something that you know has the potential to be addictive is wrong.”However, there is an important moral difference between designing a product you know might be addictive and designing it so that it is addictive, with the intent to exploit some feature of a person’s compulsive psychology. Imagine a baker intentionally included an ingredient that made his cakes addictive. And he included the addictive elements solely for the purpose of increasing sales. That’s importantly morally different from someone who makes a cake, because they are delicious and people like to eat delicious things.Video games, of any kind, provide a leisurely activity that people might have a hard time walking away from. But the kind of activity, I’m talking about isn’t merely making video games. It’s intentionally designing the games so that they include the addictive elements, specifically for the purpose of hooking people.

Objection two: Calling video games addictive is medically naive and displays a lack of awareness about the true nature of addiction. Real addiction is characterized by adverse physiological effects and withdrawal symptoms that exert pressure on a person’s will

Reply: I am well aware of this distinction, and I readily admit that there there is a big (physical) difference between someone addicted to caffeine and someone addicted (in the broader sense) to gambling (or in this case video games). However, there still likely is a big difference in the psychological makeup of someone addicted to gambling (or video gaming) and someone who is not. There is something that exerts pressure on the gambling addicts’ will that a vast majority of other people don’t experience. That difference is the morally relevant feature. So even if we shouldn’t call this “addiction”, there is something present here that deserves serious moral attention.

Objection Three: Calling video games “addictive” just serves to shield bad behavior. People can hide under the label of addiction and ask society to take it easy when judging them. These persons should still be held accountable for the negative consequences of their behavior.

Reply: I agree. But I can agree with that, and still consistently maintain that we ought to think twice about our design plans, especially if we feel ourselves tempted to include an element simply because it’s addictive.

Ultimately, it still seems clear to me that designers should examine their own intentions when developing game elements. The temptation to include elements because they are addictive is very real, and something we should all be concerned about.