Washington State is now on the cusp of passing the world’s first ban on octopus farming. The bill – which passed the State House of Representatives and Senate earlier this month – now only needs to be signed by the Governor in order to become law. The legislation is intended to halt a developing practice that leads to widespread death and suffering for octopi – not to mention other serious environmental harms.

This development marks yet another step in what is often referred to as “moral circle expansion.” What do we mean by this? Well, there are things that are worthy of moral consideration, and there are things that are not. My family, my friends, my students – indeed, all other humans – are, we assume, worthy of moral consideration. What this means, essentially, is that when making a decision, I need to factor in how the interests of those individuals might be affected. If, for example, I am about to do something that will cause severe pain to a number of those people, this will be a morally relevant consideration – and may, in fact, be sufficient to render my action morally impermissible..

There are, however, many things that are clearly not worthy of moral consideration. Most inanimate objects are like this. That’s why when my computer is slow to boot up first thing in the morning, there’s nothing morally problematic with me responding by striking it and delivering a tirade of verbal abuse. The story would, however, be much different if I treated another human in this way.

Sadly, our history is rife with examples of our “moral circle” being limited so as to exclude certain portions of the human population. Disenfranchisement, gender- and sexuality-based oppression, and the widespread suffering of ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples have all, to some extent, resulted from a failure to understand how far our moral circle should expand.

In 1975, Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation opened a brave new world of moral circle expansion by arguing that non-human animals are also worthy of moral consideration. His argument was elegantly simple, and started from the observation that most non-human animals are sentient – that is, able to feel pleasure and pain. According to Singer, sentience is all that’s required in order for something to have interests. Why? Because if something can feel pleasure then it has an interest in gaining pleasure, and if something can feel pain then it has an interest in avoiding pain. Once these interests are on the table, they must factor into our moral decision-making processes.

Almost fifty years on, Singer’s assertion might now seem rather uncontroversial. Most would probably agree that my cat has interests, and is therefore worthy of moral consideration. So too are the birds currently at the feeder outside of my window. The upshot of this is that there are many ways in which I could act towards these animals that would be clearly morally impermissible.

But, as humans, we’re rather inconsistent in our approach to moral circle expansion. While we happily include the animals with which we are most familiar – like household pets – we tend to omit vast populations of other animals – like those we farm. Many try to justify this distinction based on the perceived intelligence of the creatures in question. But this is a bad approach. Firstly, our perceptions are often mistaken. Pigs, for example, are smarter than dogs. Secondly, implying that something is less worthy of moral consideration just because it is less intelligent creates all kinds of problematic implications for how we treat very young children and those with diminished mental capacity.

Moral circle expansion gets even trickier once we start considering creatures more far-removed from humans. Recent developments suggest that our moral circle might need to be expanded to include things like fish and maybe even insects – but this is (predictably) being met with serious resistance. Something similar is now happening in Washington with octopi.

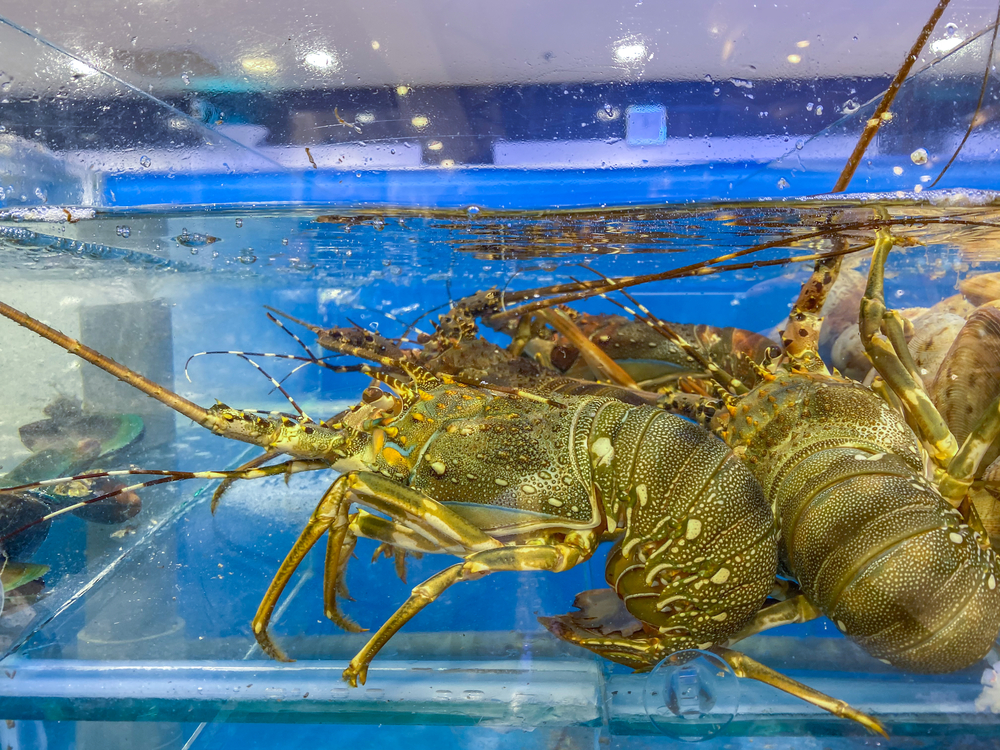

Interestingly, in 2021, the United Kingdom passed legislation recognizing decapod crustaceans (lobsters and crabs) and cephalopod molluscs (squid and octopi) as sentient beings. This recognition did not, however, automatically halt practices that would be considered morally reprehensible if perpetuated against other sentient beings. Washington State’s bill goes one step further than this, with California and Hawai’i now considering similar legislation. And such a move makes sense. Octopi are among the smartest non-human animals – able to use tools, recognize people, complete puzzles, and even open toddler proof cases that are impervious to young humans. At the very least, such abilities put them (cognitively) leaps-and-bounds ahead of many other non-human animals that we readily afford moral consideration. My cat, for example, isn’t capable of half of what an octopus can manage. So – if sentience and intelligence are what matter to moral circle expansion – cephalopods should be afforded at least as much consideration as our feline companions – if not more.

Yet they’re not. Spanish multinational Nueva Pescanova is currently planning to open the world’s first intensive octopus farm in the Canary Islands (a development that partially motivated Washington State’s new bill). And it’s this inconsistency that’s most concerning. There is, we must assume, an objective standard for what should be included in the moral circle. What’s more, most of us seem in agreement that the circle should be expanded to include many non-human animals – especially those we share our homes with. Yet, whatever standard we adopt to ensure this happens (be it sentience, intelligence, or a combination of both) there are many more non-human animals that fulfil this criteria – octopi chief among them. What this means, then, is that we must either abandon any notion of expanding our moral circle to include non-human animals in the first place; or – better yet – begin to think more carefully (and inclusively) about the range of animals that rightfully deserve moral consideration.