Is It Time to Show the Lobster a Bit of Respect?

The United Kingdom is currently in the process of revising what the law says about sentience and the ethical treatment of animals. This week news broke that the Conservative Animal Welfare Foundation has called for greater protections for non-vertebrates such as octopi and crustaceans. As a consequence, debate is emerging about whether practices such as boiling lobsters alive should be banned. Much of this debate seems to be centered on scientific facts regarding the nervous system of such animals and whether they are capable of feeling pain at all. But, perhaps this is the wrong mindset to have when considering this issue. Perhaps it is more important to consider our own feelings about how we treat lobsters rather than how the lobsters feel about it.

The ethical debate about the treatment of lobsters has mostly focused on the practice of boiling them alive when being prepared for eating. Lobsters are known to struggle for up to two minutes after being placed in boiling water and emit a noise caused by escaping air that many interpret as screaming. In response to such concerns, Switzerland, Norway, Austria, and New Zealand have all banned the practice of boiling lobsters alive and require that they be transported in saltwater rather than being kept in/on ice. But the debate always seems to hinge on the question of sentience. Can a lobster feel pain when being boiled alive? To answer that, questions of sentience become questions of science.

There is no clear consensus among scientists about whether the lobster nervous system permits it to feel pain. But how do you measure pain? To many the reaction to being in boiling water is taken as a sign that the lobster is in pain. Some studies have shown that lobsters will avoid shocks, a process called nociception where the nervous system responds to noxious stimuli by producing a reflex response. This explains why the lobster thrashes in the boiling water. However, other scientists have questioned whether the nervous system of the lobster is sophisticated enough to allow for any actual sense of suffering, arguing that a lobster’s brain is more similar to an insect. They suggest that the sensory response to stimuli is different than that to pain which involves an experience of discomfort, despair and other emotional states.

Indeed as invertebrates, lobsters do not have a central brain, but rather groups of chain ganglia connected by nerves. This can make killing them challenging as simply giving it a blow to the head will not do; a lobster must have its central nervous system destroyed with a complicated cut on the underside. It is recommended that they be stunned electronically. Because of this very different brain structure, it is suggested that lobsters lack the capacity to suffer. As Robert Bayer of the Lobster Institute describes the issue, “Cooking a lobster is like cooking a big bug…Do you have the same concern when you kill a fly or mosquito?”

Nevertheless, critics charge that this thinking is only a form of discrimination against animals with neurological architecture different from our own. Indeed, beyond nervous system reflex responses, because pain is difficult to directly measure, other markers of pain are often driven by using arguments by analogy comparing animals to humans. But creatures who are fundamentally different from humans may make such analogies suspect. In other words, because we don’t know what it is like to be a lobster, it is difficult to say if lobsters feel pain at all or if pain and suffering may fundamentally mean something different for lobsters than they do for humans and other vertebrates. This makes addressing the ethics of how we treat lobster by looking to the science of lobster anatomy difficult. But perhaps there is another way to consider this issue that doesn’t require answering such complex questions.

After all, if we return to Bayer’s remarks comparing lobsters to bugs, there are some important considerations: Is it wrong to roast ants with a magnifying glass? Is it wrong to pull the wings off flies? Typically, people take issue with such practices not merely because we worry about how the ant or the fly feels, but because it reveals something problematic about the person doing it. Even if the ant or the fly doesn’t feel pain (they might), it seems unnecessarily brutal to effectively torture such animals by interfering in their lives in such seemingly thoughtless ways, particularly if not for food. But would it all suddenly be okay if we decide to eat them afterwards? Perhaps such antics reveal an ethical character flaw on our part.

In his work on environmental ethics, Ronald L. Sandler leans on other environmental ethicists such as Paul Taylor to articulate an account of what kind of character we should have in our relationships with the environment. Taylor advocates that actions be understood as morally right or wrong in so far as they embody a respect for nature. Having such a respect for nature entails a “biocentric outlook” where we regard all living things on Earth as possessing inherent moral worth. This is because each living thing has “a good of its own.” That is, such an outlook involves recognizing that all living organisms are teleological centers of life in the same way as humans and that we have no non-question begging justification for maintaining the superiority of humans over other species. In other words, all living things are internally organized towards their own ends or goods which secure their biological functioning and form of life and respecting nature means respecting that biological functioning and the attainment of such ends.

Taylor’s outlook is problematic because it puts all life on the same ethical level. You are no more morally important than the potato you had for dinner (and how morally wrong it was for you to eat that poor potato!) However, Sandler believes that much of Taylor’s insights can be incorporated in a coherent account of multiple environmental virtues, with respect for nature being one of them. As he puts it, “The virtues of respect for nature are informed by their conduciveness to enabling other living things to flourish as well as their conduciveness to promoting the eudemonistic ends.” While multiple virtues may be relevant to how we should act — such that, for example, eating lobster may be ethical — how we treat those lobsters before that point may demonstrate a fundamental lack of respect for a living organism.

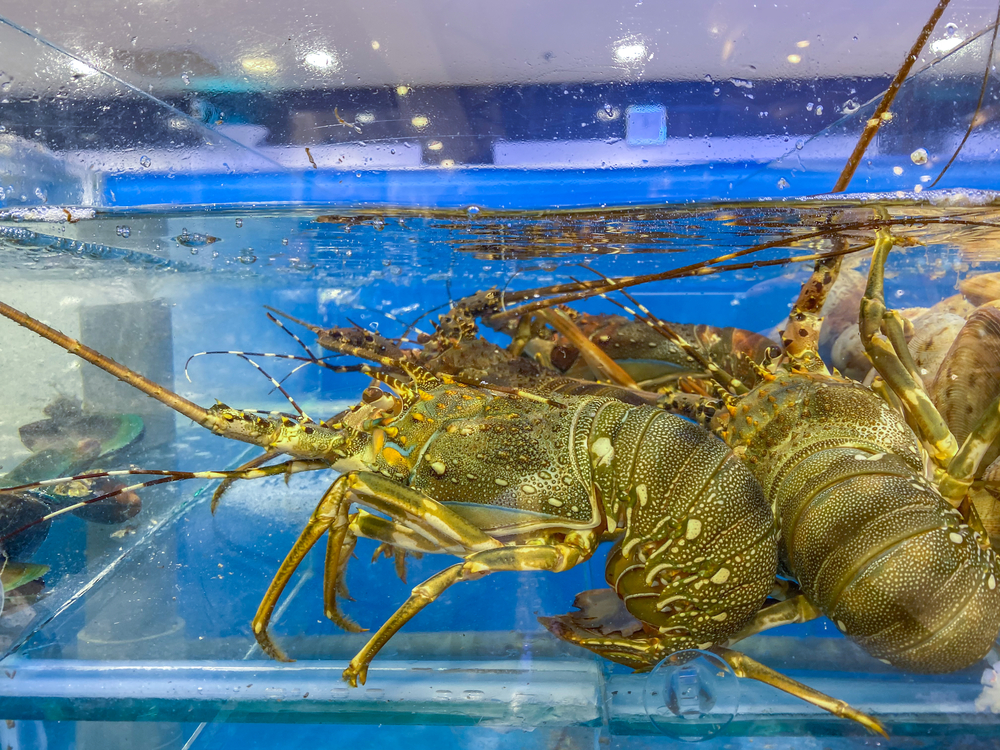

Consider the lobster tanks one finds at a local grocery store, where multiple lobsters may be stacked on top of each other in a barren tank with their claws stuck together. Many have complained about such tanks, and some stores have abandoned them as critics charge that they are stressful for the lobster. It is difficult to say that such “live” lobsters are really living any kind of life consistent with the kind of thing a lobster is. Does keeping lobsters in such conditions demonstrate a lack of respect for the lobster as a living organism with a good of its own? As one person who launched a petition over the matter puts it “I’m in no way looking to eliminate the industry, or challenge the industry, I’m just looking to have the entire process reviewed so that we can ensure that if we do choose to eat lobsters, that we’re doing it in a respectful manner.”

So perhaps the ethical issue is not whether lobsters can feel pain as we understand it. Clearly lobsters have nervous systems that detect noxious stimuli, and perhaps that should be enough to not create such stimuli for their system if we don’t have to. We know it doesn’t contribute to the lobster’s own good. So perhaps the ethical treatment of lobsters should focus less on what suffering is created and focus more on our own respect for the food that we eat.