Most of us are familiar with the idea of the psychopath – emotionally vacant, devoid of empathy, and possessing poor behavioral control. Despite psychopathy not being a recognized mental condition in its own right (or at least, not in that exact terminology), as personality disorders go, it is almost undoubtedly archetypal. Many of the names we attach to the idea of evil certainly qualify for the label, including Ted Bundy, Charles Manson, Jeffrey Dahmer, and David Berkowitz. Beyond the real world, the psychopath is also a staple of fiction, with some of the most heartless villains being written with the disorder in mind, including Hannibal Lecter, Annie Wilkes, Patrick Bateman, and Norman Bates.

However, despite these colorful examples, not all psychopaths stalk the night looking for victims. Most real-life psychopaths navigate the world without making the headlines for slaughtering the innocent or starting nationwide manhunts. For every John Wayne Gacy, there are countless more who, while being manipulative and callous, get through their lives without turning their neighbors into a rug. Indeed, estimates place the prevalence of severe psychopathy in the general population at around 1%. That means, statistically speaking, you probably know a psychopath. And while this is the general prevalence, some groups of society appear to have more psychopaths than others, such as those in corporate leadership positions (≈12%) and prisons (≈20-30%).

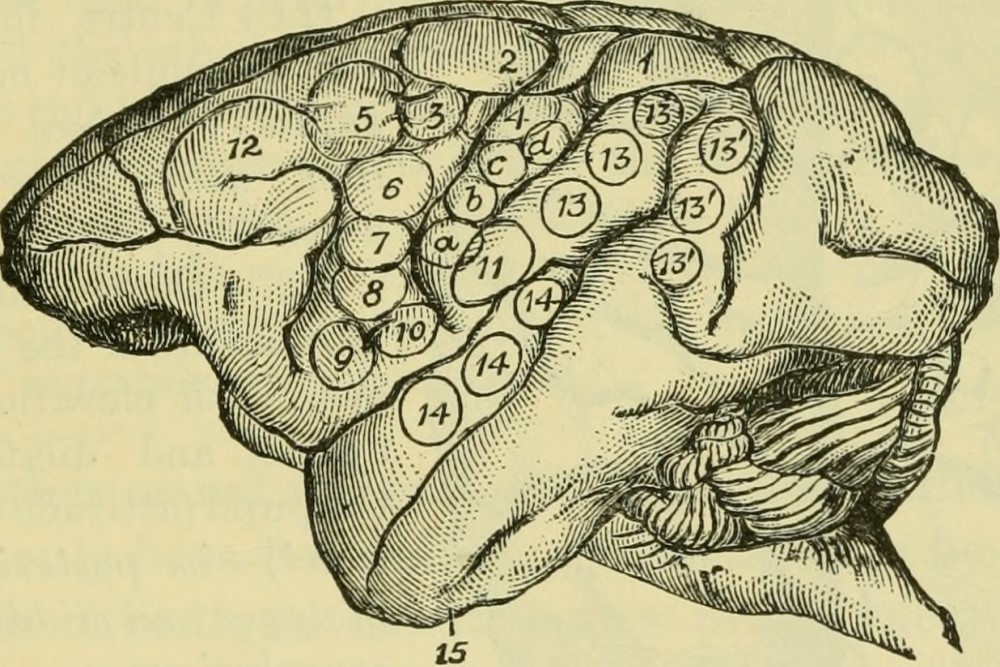

Several studies examining the brains of psychopaths have found that they appear to have abnormal neurological structures and functionality. Specifically, the areas of the brain associated with empathy are underdeveloped and lack an average level of responsiveness to external stimuli. Some suggest that this is evidence of a neurological basis for psychopathy and that the abnormal brain structure is why psychopaths behave in the way they do. Following this, others argue that, if possible, we might be justified in using medical techniques and technologies, such as neurosurgery, to alter the brains of criminally violent psychopaths, thereby removing the psychopathy and instilling a level of empathy previously absent.

But can medical techniques reducing or eliminating psychopathic tendencies be justified, or are we medicalizing a group of people out of existence to satisfy societal desire?

We often think that medical interventions, be they as minor as a course of antibiotics or as radical as brain surgery, should only occur when said intervention benefits that person. This requirement is one of the central components separating treatment from research; the former benefits the individual while the latter benefits society (and maybe the individual). While there are exceptions to this rule of thumb – living organ donation, for example – the idea that medical treatment must have some individual benefit is both widely accepted and intuitively appealing. For instance, it would be unjustifiable for a surgeon to operate on you if that operation knowingly provided no beneficial outcome. The idea of an intimate link between a medical treatment’s justification and its potential for a positive result is one of the central pillars underlying one of the most influential theories in medical ethics – principlism.

As conceptualized by philosophers Thomas L Beauchamp and James F. Childress, and formulated in their book Principles of Biomedical Ethics (now in its 8th edition), beneficence is one of the four fundamental concerns when it comes to the ethical permissibility of medical interventions; the others being autonomy, non-maleficence, and justice. According to Beauchamp and Childress, each principle is equally important when looking for ‘reflective equilibrium’ (a coherence between the principles). However, here we’ll focus on beneficence, and specifically positive beneficence, which requires persons to provide benefits wherever possible.

So, would treating psychopathy have a beneficial effect on the psychopath?

This question can be broken down into two parts: (i) do psychopaths suffer as a direct result of their psychopathy?; and (ii) do psychopaths suffer as an indirect result of their psychopathy?

Whether psychopaths suffer as a direct result of their psychopathy is, to a degree, disputed for several reasons.

First, it is unclear whether psychopathy is an illness or a disease. While we might think it causes people to act in less than desirable ways from a social standpoint, this is very different from claiming that psychopathy represents an impairment to health on behalf of the person with psychopathy. If the disorder is of a social (rather than medical) basis, then it would seem highly inappropriate to try and use medical techniques to remedy what is socially disvalued.

Second, even if we accept that psychopathy is predominately medical in nature, that doesn’t mean that its removal would provide a direct benefit. This is because the psychopath would need to experience relief from suffering in a subjective sense for such a direct benefit to occur. Much like how taking a painkiller can’t ease your suffering if you’re not in pain, psychopathy’s removal cannot provide the individual with relief if it didn’t cause suffering in the first place. From the evidence available, it’s not clear whether psychopathy does cause direct suffering. Unlike having a broken bone or terrifying delusions, there’s no clear casual line between psychopathy and suffering. Just because psychopathy is a disorder, doesn’t mean it is harmful.

However, psychopaths don’t exist in a vacuum. Like all of us, they’re situated in the world around them, alongside its complex social, economic, religious, educational, and legal systems. And psychopathy might cause suffering by separating the individual from those systems and, more generally, from society. For example, I suspect many of us would experience suffering if we went to prison for committing a crime. This type of suffering exists regardless of our personality, whether ordered or disordered, because prisons are subjectively unpleasant environments that frustrate our life plans. This is just as true for psychopaths as for everyone else; psychopaths generally don’t want to go to jail. So, by eliminating the root cause of psychopathy, we might be able to prevent psychopaths from being sentenced to prison and thus, help them avoid the indirect suffering they would otherwise experience.

This line of arguing applies beyond prisons, though. Without their psychopathic tendencies, those persons might be better equipped to engage with society, find meaningful connections with others, and empathize with the rest of humanity.

However, appeals to such indirect suffering avoidance are rarely effective for justifying medical treatments in other contexts, especially when the therapy offered has the potential to alter one of the foundations of a person’s personality. For example, we wouldn’t think that someone who lives on the street as a matter of personal preference should have their mental state altered because a result of their choice is the ostracization from society’s mainstay.

We might think their choice is odd, and we might try to convince them that they would be better off living another way of life. But this is very different from using their disordered lifestyle as a justification for a medical procedure based on the idea of harm prevention and reduction.

So what does this mean for our psychopaths? Other arguments might justify medical intervention. For example, it could be that removing psychopathy may restore that person’s autonomous decision-making (although psychopathy’s coercive potential is disputed). One might argue that, as psychopathy is so prevalent in prison populations, its elimination from that sector of society might reduce the pressure on valuable social resources (although this opens up a can of worms regarding the value of autonomy vs the interests of the state).

At the end of the day, if the availability of psychopathic-centric media is any indication, the question of how society handles psychopaths isn’t going away anytime soon, and neither are the psychopaths.