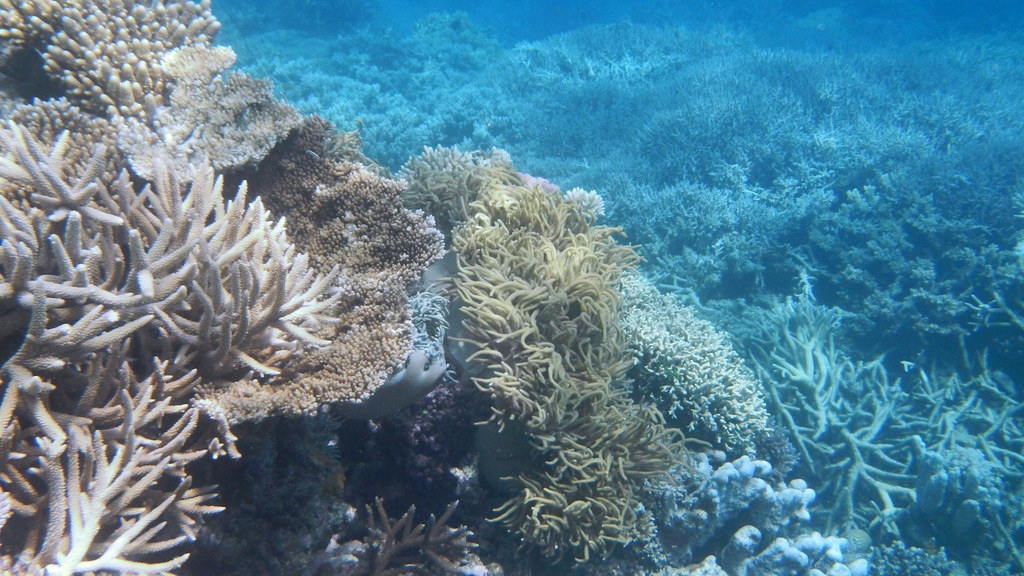

The fight to mitigate full-blown climate catastrophe last week suffered a blow thanks to Australia’s intransigence at a meeting of Pacific leaders, which culminated in a plea from the president of Tuvalu, a tiny Pacific country already being inundated by rising seas, to the world: “We ask, please understand this, our people are dying.”

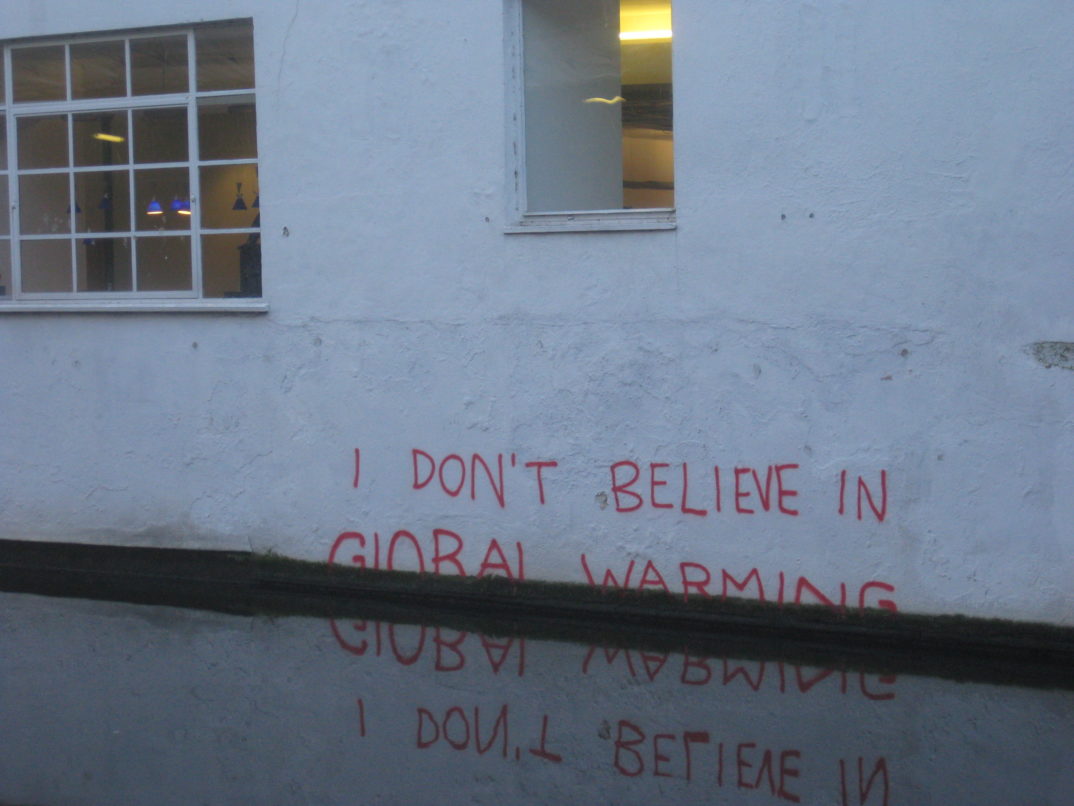

We should not be in the grip of moral uncertainty here. There is no more time to dispute the science – or to try to argue that it is in dispute. The science is in and evidence of the rapidly worsening climate crisis is all around us.

Consider this analogy: Imagine you are walking past a pond, you hear someone pleading for help and you see a drowning child.1 You have the capacity to save the child’s life, at some cost to yourself. The cost may be something relatively minor or it may be something more serious – perhaps you will be late for a class, or miss an important meeting; ruin an expensive suit, or even lose your job. None of these things, even losing your job is (without serious qualification) morally equivalent to the child’s life. It should be uncontroversial that you are morally required to save the child.

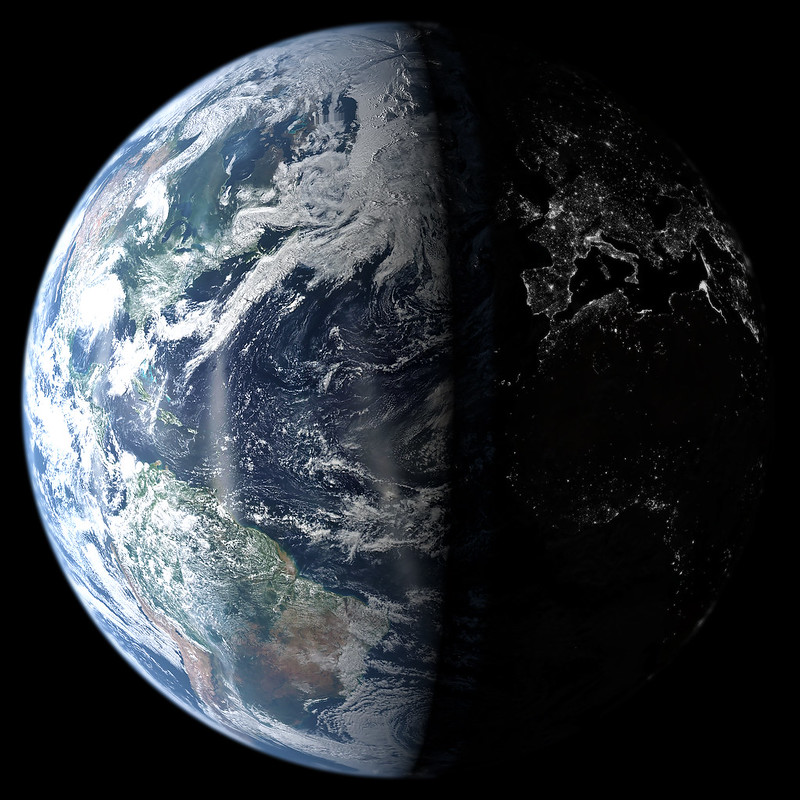

Now imagine that you are a large wealthy country strolling past a small poor nation being inundated by water as the seas rise from the effects of climate change. Imagine you hear that country pleading with you to help, to save it from drowning. Your help would of course require some sacrifice, but it will not threaten your life, or even your livelihood. It may be a major inconvenience to you, but it is a matter of life and death to the other. It should be equally uncontroversial that you are morally required to do whatever you can to come to its aid.

Something like this happened last week in the tiny Pacific Island nation of Tuvalu where leaders from a host of smaller nations along with Australia met for the annual Pacific Islands Forum. The most pressing topic of the summit was the climate emergency, as the Pacific islands are on the front line, and Tuvalu, like many other low-lying, small Pacific Island nations is facing immediate peril from rising seas. Many regional leaders had their sights set on Australia, which is becoming a notorious laggard on efforts to combat climate change and honor its commitments made in the Paris agreement. It was hoped that an agreement could be reached at the leaders summit that would reflect the urgency of the crisis and forge a cooperative strategy to address the emergency.

However, this is what those Pacific Island leaders were up against: just two years ago Australia’s Prime Minister Scott Morrison, (then federal treasurer) stood up in parliament brandishing a lump of coal and shouting that coal is nothing to be afraid of, to the guffaws of other government ministers. Morrison fronted the forum this week with his guile fully intact. Australia’s current conservative government (Liberal-National Party), now in its third term, began its tenure by repealing the previous government’s progressive and effective carbon tax, and has been defined by its ideological and pecuniary resistance to weaning Australia’s economy from its reliance on fossil fuels, especially coal, towards the many great opportunities the country affords for clean renewable energy generated by solar and wind.

Australia is one of the richest nations per capita, owing to its vast fossil fuel resources and relatively small population; Australians also have one of the highest carbon footprints per head of population and Australia is the third largest exporter of fossil fuels behind Russia and Saudi Arabia. Because of Australia’s massive coal exports, the country is a major contributor of carbon heavy fuels and bears responsibility for its own carbon output as well as that of the nations to whom its coal is exported. Australia’s lack of action on climate change, together with its plans to continue to open up new coal mining prospects is having direct impact on the imminent existential crisis faced by Tuvalu and other Pacific nations.

In his opening speech Fiji’s prime minister, Frank Bainimarama said: “I appeal to Australia to do everything possible to achieve a rapid transition from coal to energy sources that do not contribute to climate change,” he said, adding that coal posed an “existential threat” to Pacific countries.

In an effort to head off criticism the Morrison government announced $500m in climate resilience and adaptation for the Pacific region. In response Tuvalu’s prime minister, Enele Sopoaga said:

“No matter how much money you put on the table, it doesn’t give you the excuse to not to do the right thing, which is to cut down on your emissions, including not opening your coalmines.”

During the leaders’ retreat where a communiqué was debated which will be used as the basis of regional decision-making, Australia refused to budge on certain ‘red lines’ – including insisting on the removal of mentions of coal, limiting warming to under 1.5C, and setting a plan for achieving net-zero emissions by 2050, to the grief and frustration of the other nations.

The Fijian prime minister expressed his anger with the difficulties in negotiating with Australia during the leaders’ retreat, telling The Guardian that Morrison had been “very insulting and condescending.”

So, to return to the drowning child scenario, it is meant to help us see that where it is in our power to help someone whose life is in danger “without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, we ought, morally, to do it.” Australia has failed the test. It has walked past the child, refusing to help on the basis of reasons which are not morally equivalent – as Sopoaga said he told Morrison at one point during discussions: “You are trying to save your economy, I am trying to save my people.”

But there is another stratum of moral bankruptcy to how the broader conversation in Australia went. Australia’s deputy Prime Minister Michael McCormack, offering his own commentary back home from a business function as the forum was underway in Tuvalu, told an audience

“I also get a little bit annoyed when we have people in those sorts of countries pointing the finger at Australia and say we should be shutting down all our resources sector so that, you know, they will continue to survive,”

The current Australian government not only doesn’t understand its moral obligations or isn’t prepared to meet them, but has no compunction about flouting its preference for its resource sector (lets say its expensive suit) over the survival of its neighbors (the drowning child).

1 I am here borrowing, and adapting an analogy used by Peter Singer in his paper Famine, Affluence and Morality, published in 1972.