Eco-dystopias: What Fiction Can Teach Us About Climate Change

Throughout the past several decades of climate change discourse, contemporary environmentalism has warned of an impending ecological apocalypse. Even before the rise of global climate change discourse in the 1980’s, “eco-dystopic” fiction emerged as a genre in fiction and film. In the 1950’s, eco-dystopias like John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids and John Christopher’s Death of Grass emerged. Wallace McNeish argues in his article “From revelation to revolution: Apocalypticism in green politics” that “dystopia has replaced utopia as the dominant mode of speculative cultural imagination.”

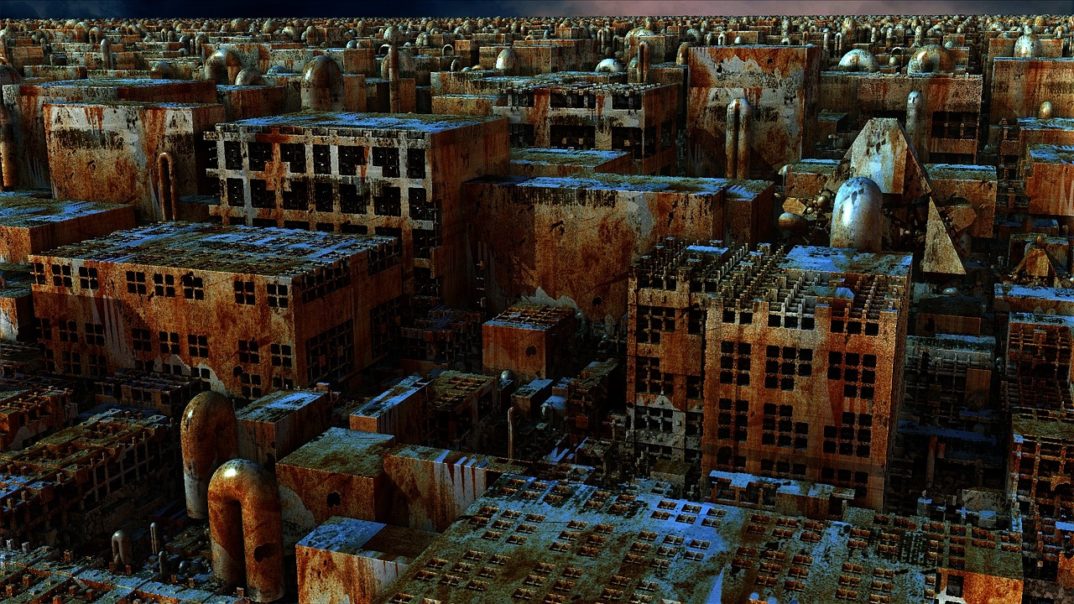

This eco-dystopic theme is just as prevalent today as it’s been decades before, with series like The Hunger Games and Divergent becoming best-selling books and movies. These eco-dystopian stories depict post-apocalyptic societies in which some sort of ecological catastrophe has occurred, including scarce natural resources and a damaged agricultural system. Why is this theme so popular in fiction today, and what does it show us about our own attitudes towards climate change?

One popular argument is that “cli-fi,” climate change fiction, is especially popular in the United States because it helps us cope with the current administration’s policies towards climate change. In a country where climate change data is erased or ignored, the Paris Climate Accords are rejected, and the Environmental Protection Agency is in jeopardy, dystopian novels offer relief both by acknowledging our current situation and by imagining a future afterwards. Murat Cem Menguc argues that dystopian fiction “imagines that one day such idiocies will be washed off clean, and the earth will continue its adventure…if anyone is left to survive, they would most likely strike a far better covenant with this planet than the one we have at present.” Dystopian novels force us to grapple with fears that are not too far from the present reality.

However, one danger in dramatizing climate change is that it can be perceived as entertainment. The 2004 film The Day After Tomorrow has been thoroughly studied to see if it had any significant impact on popular opinion concerning climate change, especially since the makers of the film publicly acknowledged their belief that the film could potentially address climate change. For example, the article “Does tomorrow ever come?” gathered empirical evidence that any potential benefits of the eco-dystopian film were short-lived. One respondent compared the experience to watching the zombie film 28 Days Later; although one might start thinking about how they would prepare for a zombie apocalypse, those ideas are not taken seriously. This study also found that a number of respondents were confused about the realistic possibility of the events in the movie, and may have taken the message more seriously if the film had been produced or endorsed by legitimate scientific organizations. Overall, the movie was still perceived as Hollywood drama.

Although the risk of catastrophizing is inherent in all fictional renderings of climate change, dystopian fiction and film offers an important platform to start talking about how climate change induced ecological disasters can be averted. A conference held at Monash University last December explored just that–the potential for dystopian works to prompt discussion about present and looming problems in society. In an article referencing popular dystopian works like 1984 and The Handmaid’s Tale, conference attendee and PhD candidate Zachary Kendal stated, “Now is an ideal time to interrogate those dark imaginings and how to steer society away from the oppressive futures they envisage.” Especially with the current administration’s policies towards climate change, dystopian novels feel uncanny and familiar, and offer both emotional relief and a chance to discuss how we can avoid making those imagined futures a reality.