Unsafe abortions are the leading cause of preventable maternal deaths world-wide. At least some of the laws that restrict access to abortion also, unavoidably probably, make it less safe. If pursuing more restrictive abortion laws makes it less safe, but we believe abortion is immoral, we might wonder how to balance the health and safety of women who pursue abortions against the goal of reducing the number of abortions. Which raises the question, do restrictive abortion laws reduce the number of abortions?

They do not. The restrictiveness of abortion laws and policies has no overall effect on the number of abortions performed. Given this, even if we suppose that abortions are morally problematic, why make them illegal?

Since we know that these laws will result in more harm to women without preventing fetuses from being aborted, why do it?

We might be tempted to think that everything that is immoral should be illegal. But this is not plausible. One deep reason to deny that everything immoral should be illegal is that our society is founded on the idea that we should each be allowed to pursue our own good, as we understand it, in our own way. At most, the law represents a kind of ethical ground floor that must leave room for citizens’ reasonable disagreement over fundamental matters. What form should that take in the specific case of abortion? That’s a contentious matter. Certainly some would argue that the conflict in the abortion case pits the life of the fetus against the liberty of the mother, and so (as they say) we should choose life.

However, another reason not to criminalize all immoral behavior is that it’s just not possible. Could society function and not go broke, if we policed, arrested, tried, and punished everyone for any lie they told or every time they broke a promise? Perhaps, we should make only seriously immoral things illegal – and abortion, some would argue, is seriously immoral in a way most everyday lying is not. But why bother if making something illegal does not prevent people from doing these things – and at roughly the same rate?

Maybe, seriously immoral things should be illegal, even if that doesn’t prevent them. Perhaps we can justly punish people for their bad behavior, even if such punishment does not increase the overall good and instead makes everyone worse-off. It makes the punished worse-off, obviously, but since, again, it also costs time and social resources to police, arrest, try, and punish crimes, it makes the punishers worse off too. Some people, including most famously the philosopher Immanuel Kant, believe in what is called the “retributive theory of punishment.” We should punish people for doing bad things without regard to the consequences. Punishing people appropriately, and proportionally, for the wrongs they have done does, in fact, make them, and us, better off in some metaphysical sense, retributivists say, even if it doesn’t increase our welfare.

The trouble with taking this view in this context is that American anti-abortion activists have long dismissed as insulting the suggestion that they are mainly interested in punishing women. Instead, defenders of restrictive abortion laws often argue the point is not to punish women, but doctors and other abortion providers. Arguably, this is inconsistent. They both participated in the same crime, on this account, and both have to bear serious consequences. Given the impact on maternal health coupled with the ineffectiveness in curbing abortion’s frequency, it’s hard to see the point of criminalizing abortion as anything other than the punishment of women.

Perhaps, some things should be illegal because they are wrong and we need to send a message to society as a whole that we will not endorse such behavior. In other words, maybe making abortion illegal is a kind of virtue signaling or moral grandstanding. Marking something as wrong symbolically, however, can be done symbolically. We could just send a message.

But some might think that more than a message is needed. We might think that, at a minimum, we have a moral duty to avoid providing any sort of aid or assistance to others doing what we regard as wrong. In the United States, the Hyde Amendment has forbidden the government from financially supporting abortion-related care for over twenty years. Given its impact on maternal health, this might not be a good thing. But it does suggest that the debate over who pays for abortion-related healthcare is not the same as the debate concerning whether abortion should be outright illegal.

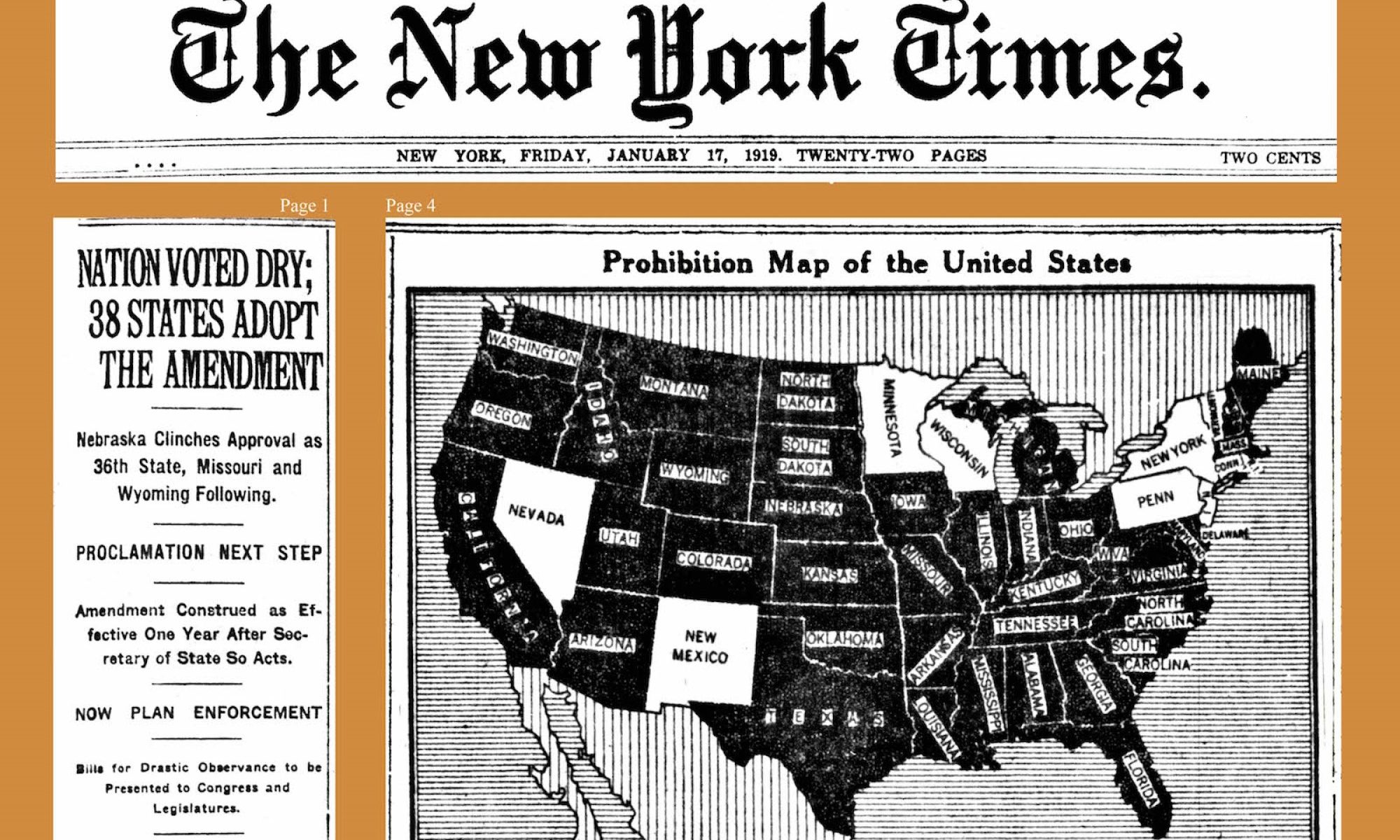

There are other crimes that are not reduced by prohibition, but were, or still are, illegal. Prohibition, for example, prohibited (or, really, limited) alcohol consumption. But that only lasted thirteen years, mostly because it increased violent crime more than it reduced alcohol consumption. Similarly, the U.S.’s “war on drugs” has been going on for fifty-years and seems to have produced unprecedented levels of mass incarceration, especially of people of color, without limiting drug consumption. In fact, the government is starting to give up on marijuana prohibition. So, rather than thinking that abortion, like alcohol, or other drugs should be illegal, this analogy might actually support less restrictive abortion law. We might think that the lesson of the analogy is not that we should criminalize abortion care, but that is time to call a truce in the war on drugs.

Why is it that restrictive abortion laws do not lower the abortion rate? It’s no doubt partly that, like alcohol and other drugs, the demand is high and doesn’t change. As economists say, the demand is inelastic. However, it’s also because societies with more restrictive abortion laws also typically have more laws restricting access to contraception. In theory, we could reduce the abortion rate by making access to contraception easier. Though anti-abortion activists have increasingly been arguing that many kinds of contraception are actually forms of abortion. Unfortunately, this is a problem we can’t take on here.

But you can read other great Prindle Post articles on the moral and legal issues surrounding abortion, and check out my article “’Persons’ in the Moral Sense.”