Let’s say you go onto a website to find the perfect new item for your Dolly Parton-themed home office. A pop-up appears asking you to sign up for the website’s newsletter to get informed about all your decorating needs. You go to click out of the pop-up, only to find that the decline text reads “No, I hate good décor.”

What you’ve just encountered is called a manipulink, and it’s designed to drive engagement by making the user feel bad for doing certain actions. Manipulinks can undermine user trust and are often part of other dark patterns that try to trick users into doing something that they wouldn’t otherwise want to do.

While these practices can undermine user trust and hurt brand loyalty over time, the ethical problems of manipulinks go beyond making the user feel bad and hurting the company’s bottom line.

The core problem is that the user is being manipulated in a way that is morally suspect. But is all user manipulation bad? And what are the core ethical problems that manipulinks raise?

To answer these questions, I will draw on Marcia Baron’s view of manipulation, which lays out different kinds of manipulation and identifies when manipulation is morally problematic. Not all manipulation is bad, but when manipulation goes wrong, it can reflect “either a failure to view others as rational beings, or an impatience over the nuisance of having to treat them as rational – and as equals.”

On Baron’s view, there are roughly three types of manipulation.

Type 1 involves lying to or otherwise deceiving the person being manipulated. The manipulator will often try to hide the fact that they are lying. For example, a website might try to conceal the fact that, by purchasing an item and failing to remove a discount, the user is also signing up for a subscription service that will cost them more over time.

Type 2 manipulation tries to pressure the person being manipulated into doing what the manipulator wants, often transparently. This kind of manipulation could be achieved by providing an incentive that is hard to resist, threatening to do something like ending a friendship, inducing guilt trips or other emotional reactions, or wearing others down through complaining or other means.

Our initial example seems to be an instance of this kind, as the decline text is meant to make the user feel guilty or uncomfortable with clicking the link, even though that emotion isn’t warranted. If the same website or app were to have continual pop-ups that required the user to click out of them until they subscribed or paid money to the website, that could also count as a kind of pressuring or an attempt to wear the user down (I’m looking at you, Candy Crush).

Type 3 manipulation involves trying to get the person to reconceptualize something by emphasizing certain things and de-emphasizing others to serve the manipulator’s ends. This kind of manipulation wants the person being manipulated to see something in a different light.

For example, the manipulink text that reads “No, I hate good décor” tries to get the user to see their action of declining the newsletter as an action that declines good taste as well. Or, a website might mess with text size, so that the sale price is emphasized and the shipping cost is deemphasized to get the user to think about what a deal they are getting. As both examples show, the different types of manipulation can intersect with each other—the first a mix of Types 2 and 3, the second a mix of Types 1 and 3.

These different kinds of manipulation do not have to be intentional. Sometimes user manipulation may just be a product of bad design, perhaps because there were unintentional consequences of a design that was supposed to accomplish another function or perhaps because someone configured a page incorrectly.

But often these strategies of manipulation occur across different aspects of a platform in a concerted effort to get users to do what the manipulator wants. In the worst cases, the users are being used.

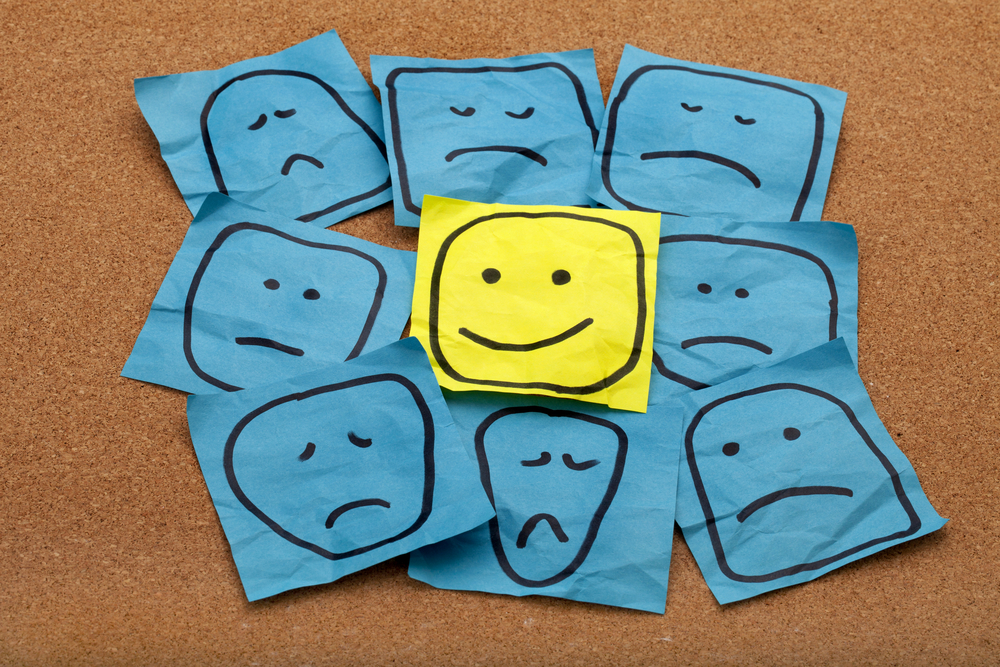

In these worst-case scenarios, the problem seems to be exactly as Baron describes, as the users are not treated as rational beings with the ability to make informed choices but instead as fodder for increased metrics, whether that be increased sales, clicks, loyalty program signups, or otherwise. We can contrast this with a more ethical model that places the user’s needs and autonomy first and then constructs a platform that will best serve those needs. Instead of tricking or pressuring the user to increase brand metrics, designers will try to meet user needs first, which if done well, will naturally drive engagement.

What is interesting about this user-first approach is that it does not necessarily reduce to considerations of autonomy.

A user’s interests and needs can’t be collapsed into the ability to make any choices on the platform that they want without interference. Sometimes it might be good to manipulate the user for their own good.

For example, a website might prompt a user to think twice before posting something mean to prevent widespread bullying. Even though this pop-up inhibits the user’s initial choice and nudges them to do something different, it is intended to act in the best interest of both the user posting and the other users who might encounter that post. This tactic seems to fall into the third type of manipulation, or getting the person to reconceptualize, and it is a good example of manipulation that helps the user and appears to be morally good.

Of course, paternalism in the interest of the user can go too far in removing user choice, but limited manipulation that helps the user to make the decisions that they will ultimately be happy with seems to be a good thing. One way that companies can avoid problematic paternalism is by involving users at different stages of the design process to ensure that user needs are being met. What is important here is to treat users as co-deliberators in the process of developing platforms to best meet user needs, taking all users into account.

If the user finds that they are being carefully thought about and considered in a way that takes their interests into account, they will return that goodwill in kind. This is not just good business practice; it is good ethical practice.