Our public discourse [is] full of blak [sic] bodies but curiously empty of people who put them there. Alison Whittaker

This weekend protestors for Black Lives Matter in Australia took to the streets in contravention of Covid-19 health warnings to join worldwide protests sparked by the murder of George Floyd to highlight police violence against people of color and to once again raise the issue of Aboriginal deaths in custody.

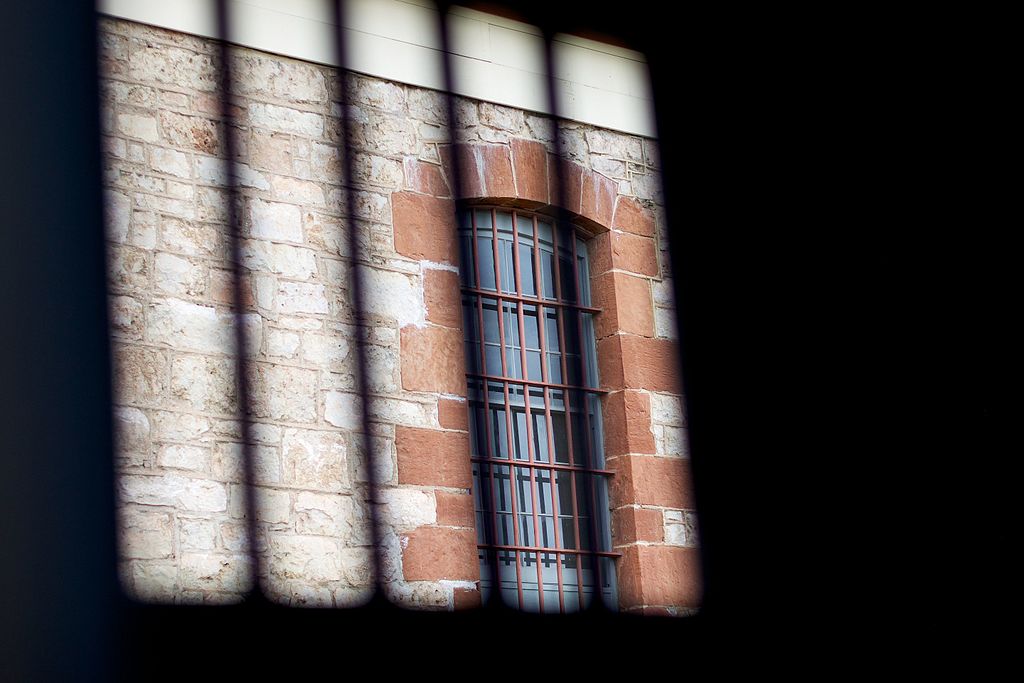

The statistics and the stories of Black deaths in custody is a vexed issue in Australia, and a national disgrace. In the 30 years since a royal commission was conducted, successive governments have failed to implement many of its key recommendations; and in that time 432 Aboriginal Australians have died in police custody. Despite the manifest violence, negligence, and displays of overt racism around these deaths, charges against police are rarely brought, and there has never been a conviction for an Aboriginal death in custody in Australia.

Indigenous activists and families of victims have been trying, with only incremental and limited success, to elevate the issue in the wider Australian public. Most of the names and stories of these people are not known to most Australians.

In a piece for The Conversation, Alison Whittacker, law scholar, poet and Australian Indigenous activist, writes,

“Do you know about David Dungay Jr? He was a Dunghutti man, an uncle. He had a talent for poetry that made his family endlessly proud. He was held down by six corrections officers in a prone position until he died and twice injected with sedatives because he ate rice crackers in his cell. Dungay’s last words were also “I can’t breathe”. An officer replied ‘If you can talk, you can breathe.'”

The statistics for Aboriginal incarceration in Australia are mind-blowing. In some areas in the country, Aboriginal people are the most incarcerated people on earth; They make up roughly 3.3% of the overall population but account for 28% of the prison population. Aboriginal women represent 34% of the overall national female prison population.

The 460 deaths in custody since 1990 is a terrible number, and to each belongs a story – a life, and then a death of indignity, of violence, of neglect. As in the US, in Australia it belongs to an historical legacy of rapacious, brutal colonial expansion.

May 27 to June 3 is Australia’s National Reconciliation Week. These dates mark two significant milestones for Aboriginal people. One is the 1967 referendum, which for the first time recognized Aboriginal Australians as citizens. The other is the High Court native title decision known as Mabo, which overturned the legal doctrine of ‘terra nullius’ – the principle by which the Crown acquired sovereignty of the continent in 1788, on the basis that the lands were lands ‘belonging to no one.’

But there is still a long way to go for Australians to come to terms with the history of frontier wars, which morphed into state maintained forms of oppression and violence, and then into official government policy of forced removal of Aboriginal children from their families. This history is not visible enough to, nor unflinchingly acknowledged by, wider Australia. Nor are the tendrils visible which reach through that history into the present, holding Aboriginal people in all sorts of disadvantage. Disadvantage that is reflected in the statistics. As the Uluru Statement from the Heart says:

“Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people. Our children are aliened from their families at unprecedented rates. This cannot be because we have no love for them. And our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers. They should be our hope for the future. These dimensions of our crisis tell plainly the structural nature of our problem. This is the torment of our powerlessness.”

What, at this time, now, can be said and done about the work of reconciliation? In 2000, 300,000 people walked across Sydney Harbour Bridge to show their support for reconciliation. This year, then, marks the twentieth anniversary of ‘the bridge walk’. Yet material change has been frustratingly slow, and in some indicators, things are going backwards.

The 2018 Close the Gap report on Indigenous health and education targets and outcomes found child mortality at twice the rate for Aboriginal children, school attendance rates declining, and a persistent life-expectancy gap of almost a decade between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

Perhaps reconciliation has had its moment. It was maybe only the first word Australians have learned in the lexicon of change and of justice. Recognition of the nation’s shameful history is a starting point on the long road to equality and justice. But perhaps it has become a platitude, a way for white Australians to settle the ledger of their guilt, a way to paper over deep-seated systemic injustice that is thwarting real progress for Aboriginal lives and that continues to create privilege for settler Australians.

The problem, as many voices have been saying (for a long time but) especially in the weeks since the BLM protests broke out in the US following the murder of George Floyd, is that white and settler oppression of Black and Indigenous people is thoroughly baked in to the system; baked into the system of colonial expansion– which included slavery and dispossession under terra nullius (both mechanisms used to dehumanize people for the purpose of wealth creation) – and it is baked into its neoliberal iterations.

Perhaps the problem, rather, is that we have been reconciled to these things, to the reality of Indigenous disadvantage and risk of police violence and incarceration, for too long.

How, then, can we reimagine and re-engage the concept, the work of reconciliation, or do we need to move beyond it to another stage? The national conversation in Australia has been painfully slow to get going.

National Sorry Day is marked on May 26th, began in 2007 when the Australian Government, following the release of the Bringing Them Home report, formally apologized to Aboriginal people who were forcibly removed as children from their parents in a government assimilation policy.

Australian philosopher Raimond Gaita writes that the findings of the report “[were] a source of deep shame for many Australians, and for some a source of guilt” ( A Common Humanity, 1999, pg. 87). While, as Gaita observes, many people feel shame and guilt, many also resisted such feelings, and felt that they were being asked to take responsibility for past wrongs they felt no part of.

The refusal of shame sometimes takes the form of national pride, in which being proud of one’s nation is mutually exclusive with acknowledging its brutal history and recognizing the remnants of that history.

Those who hold this conception of national pride take the view that history in which racial injustice is afforded a more central place in our story and our journey to self-understanding is overly bleak. It is known by its detractors as the ‘black armband view of history’ and they argue that we should be focusing on trying to fix the current inequalities rather than looking backwards into a troubled past. This obviously ignores the fact that these current inequalities, created by that past, are able to continue because it has never been reckoned with.

Therefore the corrupted, shallow conception of national pride can never do anything other than let the deep national wounds fester. To be authentic in our attempts to reconcile, we should not contrast our national truth telling with our national interest, and reconciliation cannot be about ‘moving on’ until the appalling statistical gaps between white and black Australia are well and truly closed.

But the injustice is not just expressed in the material conditions (by these gaps), or even the systemic problems. Simply moving forward means that there is no proper acknowledgement that those who suffered — and continue to suffer these injustices — are wronged, and that to be wronged, is itself a distinctive and irreducible form of harm.

Jacqueline Rose, on the 2018 conference on ‘Recognition, Reparation and Reconciliation’ in Stellenbosch, South Africa, wrote: “thinking was not enough. Not that ‘feeling’ will do it either, in a context where expressions of empathy – ‘I feel your pain’ – are so often a pretext for doing nothing.”

Guilt and shame are part of a pained acknowledgement of wrongs we have committed or in which we are in other ways implicated. But they must also be part of what forces us to change the system and ourselves.

As protests in response to George Floyd’s murder and in support of the Black Lives Matter movement against systemic racialized violence and oppression raged across the US last week, a Sydney police officer was filmed handcuffing and then sweeping the legs out from under a sixteen-year-old Aboriginal boy who had just issued a vulgar verbal threat; the officer slammed the boy’s face into the pavement.

Shortly afterwards the New South Wales police minister defended the officer, saying he was provoked and threatened. The minister, in public remarks, expressed far more outrage at the verbal abuse from the teenager than at the officer’s brutal response.

How can reconciliation occur if such blatant power differentials cannot even be recognized, if the historical weight of wrongs done to a people and the humiliation and disadvantage they continue to suffer is totally invisible? Nothing, then, has been reckoned with.

The worst thing about this story from Sydney is the grim, horrific moral equivalence being drawn between a lippy teenager and an officer of the law, whose duty is to ‘protect and serve’ using brutal and retributive force.

When a teenager can be face-slammed for giving a mouthful of foul language to a police officer and this act can be defended by his superiors as a response to a threat, we are nowhere.