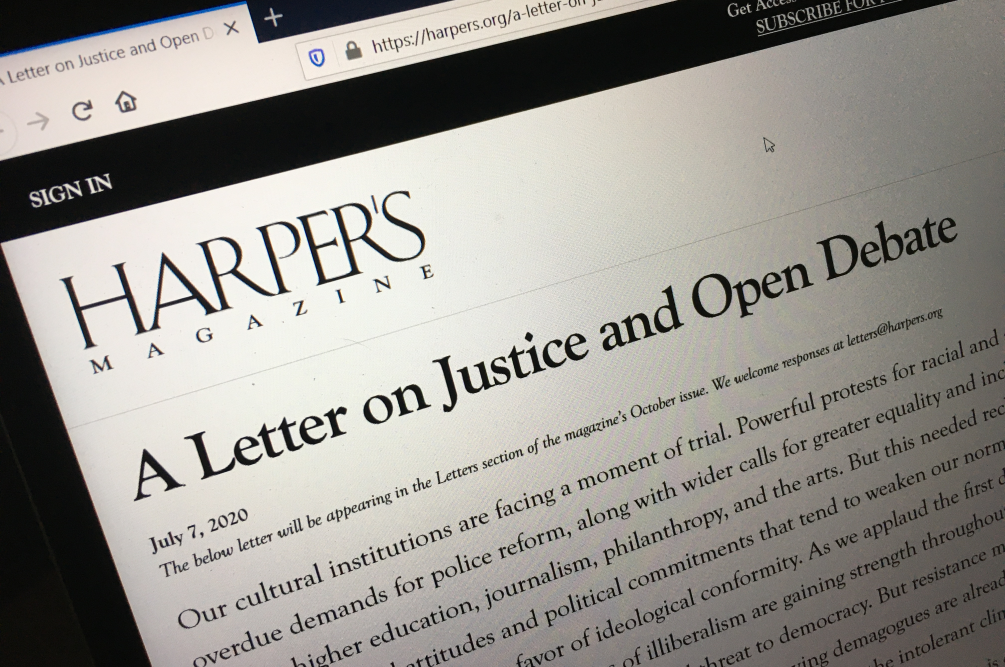

This piece is part of an Under Discussion series. To read more about this week’s topic and see more pieces from this series visit Under Discussion: The Harper’s Letter.

Many individuals in the public sphere have signed an open letter referred to as the Harper’s Letter. The gist of the letter is that the free discourse of ideas is currently being hampered by what has been called “cancel culture” — the sudden and wide-ranging criticism that individuals in the public eye are subject to when private citizens find their speech or behavior unacceptable. The undersigned of this letter represent all manner of points across the political spectrum and a variety of professions.

The letter itself tends to fixate on contributors who occupy a privileged position in public debate: editors, authors, journalists, professors. In focusing on the figures with high-impact voices in public dialog, the letter misses important features of open discourse. As participants in dialog, there are responsibilities we have to one another as speakers, as contributors to our public discourse. We do not voice opinions, or indeed act, in a vacuum. We speak and operate in contexts where a great deal of our meaning is determined by our intended audience and the conversations we are entering into. In short, what we say and do depend on the world around us for its meaning and impact.

The public figures that signed the Harper’s letter have received public sanction for their speech and behavior, and the letter comes off as a complaint about the public consequences of their own behavior as it does their characterization of public discourse in general. When speaking as a public figure, or occupying a privileged position in public discourse in general, your voice has a context that is open to criticism by a broad audience, and, unfortunately for some, that audience finds their voices wanting.

No one deserves to occupy a particular space in the public sphere in our society, or to be above criticism. No one deserves to be in a privileged position, such as editors, authors, and other media figures who speak to the public. Such figures are open to criticism and bear the consequences for their behavior according to public judgment and standards just as private members of the community do, but at the scale of their privileged position. No one has to listen to them or subject them to “exposure, argument, or persuasion” (as the Harper’s Letter seems to demand of immoral and toxic, misinformed behavior and speech that is particularly damaging to society when amplified by these privileged voices).

We have categories that limit harmful speech, such as “harassment,” “libel,” and “slander” that handle those instances where criticism becomes out of line, but the Harper’s Letter equates publicly criticizing speech or figures being de-platformed with being “silenced.” If one’s livelihood depends on public opinion, then part of their professional expertise is managing their public image, and they have not performed it adequately when they are subject to the amount of public criticism that the undersigned describe.

However, it may be more or less appropriate to take public criticism as the standard by which the speech of individuals should be judged. As public figures, we can, for instance, consider what the standards are for your position as a public figure? Depending on the grounds for the attention and status you have, public criticism may be more or less warranted, or perhaps should have more or less of a degree of impact on your life and career.

An example from the letter regards issues with faculty in universities. On occasion, professors’ scheduled talks at other universities have been met with student protests, making them unable to present their speech. These cases are complicated, as faculty aren’t exactly public figures, but when they are asked to speak, they are being given a voice above other possible speakers — it is not part of their explicit job, and the inviting institution had options for which voices to promote. In that sense, criticism by the audience can be appropriate regarding the speech. Audiences are constituent members of acts of speech, and speakers don’t inherently deserve one. On the wider professional level in academia, your research is judged by your peers, and you are not a privileged speaker or public figure. When your peers find your scholarship wanting, your speech is silenced according to some loose standard. Such an incident happened recently with Daniel Feller, the historian who gave the Plenary Address at the 2020 Shear Conference. Professor Feller drew criticism when his speech diminished the atrocities committed by Andrew Jackson against Native Americans, with many of his peers submitting scholarly evidence countering the points in his speech.

There are further examples where individuals draw criticism for their speech and behavior that are in line with the undersigned’s personal grievances. With individual figures whose careers are primarily in the public sphere, the standards for criticisms can be more amorphous. Whether they should have a career, or whether their place in the public eye should be actively discouraged, could depend on a number of things.

For instance, one complicated example of publicity and criticism concerns businesses and the sudden, large outcry policies and statements can provoke. Large numbers regularly criticize business leaders in and the direction of their profits, calling for their removal from their positions or boycotting their companies’ goods. Chik-fil-A, Soul Cycle, and LaCroix are just a few recent examples. These leaders have a very privileged position; economic realities influence the political reality in an extreme way in the United States. As of 2015, corporations spend more money lobbying Congress than taxpayers spend funding Congress.

It might be helpful to consider other comparisons. Civil servants, for instance, depend on their constituents for their legitimacy. If their voters disagree with anything about their lives, conduct, opinions, or personality, it is sufficient for them to lose their justification for having that position. The grey area here is the connection between celebrity and political role. Often in order to remove someone from their role in politics, public messaging plays a large part and this involves open criticism that damages reputations and employs strategies that are frequently controversial. This is also the feature that makes public criticism and campaigning to remove individuals from the public roles they occupy difficult to parse.

News anchors and other media figures explicitly depend on their behaviors and speech to be understood in particular ways and to meet societal standards where sufficient amounts of their audience approve of their speech and behavior. When their speech and behavior elicits sudden and large public outcry, this is a professional rather than a personal issue, more similar to civil servants than academics.

For artists, the connection between creating art and the celebrity it can bring is more complicated than for civil servants and media figures. If artists take on the mantle of public figure, they also take on the potential for public criticism and blame.

There are two identifiable threads that people find alarming when sudden and marked criticism targets public figures. First, it can seem undeserved, or an overreaction, in which case the outcry seems unjust, or unfairly backing someone into a corner or painting one with too broad a brush. This leads to a defensive response by the object of criticism, and a vulnerable and defensive reaction by some of the audience of the events. The response this engenders denies that the wrongdoing was “all that bad.” It suggests that we should be more tolerant to the behavior that is being called out.

When the defensive reaction elicits a denial of the misstep or outright wrong of the public figure, this can obviously be very problematic. Everyone goes wrong at multiple times in their life be it through behavior, speech, or intention. Public figures *do* go wrong, just as private members of society do. We need to not only acknowledge that, but also take seriously the over-sized impact that public figures have in our society: they influence our communities more than private members do. The increased impact brings with it more responsibility for critical reflection.

It is *wrong* for J.K. Rowling to promote transphobic and hateful positions, just as it is *wrong* for Louis C.K. to commit sexual misconduct. It was similarly wrong for Chik-fil-A to promote damaging and hateful treatment of LGBT+ people. Al Franken lost his political position over allegations of sexual misconduct, and Matt Lauer was removed from the “Today” show due to allegations of rape and sexual misconduct. These examples are of entities that exist in the public sphere, and who faced backlash and criticism based on their expressed views or behavior. Just as there’s not a justification for them to be in the public sphere in the first place, there is not a justification for them to be exempt from losing their place after enough people take issue with their behavior.

Second, it can seem as though there is no possible way to behave in such a way to avoid the strong backlash that some public figures have received. This amplifies the vulnerable, threatened feelings not just among the public figures, but also private members of society who might identify with those behaviors. It may seem that there is no getting away from some types of criticism, of going wrong in some sort of way. And this kind of condemnation cuts off further conversation about repair and progress.

Consider the months in 2019 when many public figures were exposed for having worn blackface in the past. Unfortunately, few who were revealed to have taken part in this obviously offensive and unacceptable behavior took responsibility for their actions. Few admitted to having done something wrong, expressed regret having since learned what made their actions unacceptable, or indicated that they were grateful to those who helped them grow and reflect on their former understanding, etc. The idea that there is no way to respond to criticism or wrong-doing does not help progress or understanding. Again, people will make mistakes. While nearly everyone will not make the mistakes listed here, it could be earnest dialog rather than defensiveness that is the focus when communal moral standards are not met. When private members of society see public figures being castigated, it is an important step past the fear of “cancel culture” to realize that they themselves are not under threat and that most likely they would not do what these figures did in the first place. It is also important to keep in mind that our moral missteps be approached with an attitude geared toward growth and repair.

Adopting such an attitude can be an extremely difficult task. As the Harper’s Letter attests, the criticism that occurs on social media — and that criticism’s real-life consequences — encourage defensive reactions. The threat wielded by such sudden and effective criticism evokes feelings of vulnerability and insecurity. But it is important to remember that it is the place in the public eye, or one’s professional reputation that is under threat, not the person’s safety or even freedom of speech. Further, threatening their place in the public sphere is frequently warranted, especially when their profession confers public status, as with politicians, news anchors, celebrities, etc.

In the end, the discussion of freedom of speech is a red herring that distracts us from our principal target. We should instead be focusing on why individuals receive the attention that they do, and whether the appropriate form of moral engagement when they fail to meet moral standards is to criticize their place in the public sphere. This can result in mutual progress, as opposed to mere removal.