The coronavirus pandemic has resulted in massive increases in government spending. Many governments around the world are scrambling to cover lost wages, provide benefits to those who are hit hardest by COVID, and to stimulate economic growth to ensure an economic recovery once the pandemic ends. Yet, with deficits of several nations hitting levels not seen since the Second World War and with more deficit spending still expected there are long term concerns about how all of this spending will be paid for. Because of this, several economists are now suggesting that this may be the time to seriously consider taking an approach consistent with modern monetary theory (MMT). However, MMT carries with it broad and far-ranging ethical consequences.

This year the U.S. federal government’s deficit is set to be a fourfold increase over last year (3.8 trillion dollars). The Canadian federal government’s deficit is likely to be over eighteen times larger than it was last year (343 billion dollars). Many other governments are also spending modern record deficits. One approach to dealing with this crisis is to essentially repeat the response to the 2008 recession; stimulate the economy and then commit to austerity by cutting spending and/or raising taxes. Another approach would be to adopt policies that are in keeping with MMT which would allow for increases in the supply of money to stimulate the economy instead of relying on taking on larger government debt.

Modern monetary theory is less a normative theory than it is descriptive. It requires a bit of a paradigm shift in thinking. Obviously, MMT and its relationship to modern economies is complicated, so I will focus on a few relevant points to addressing certain moral concerns. According to current understandings, governments must raise revenue through taxation or by taking on debt by selling bonds. Traditionally that is how things needed to work under a system like the gold standard. However, modern currencies such as the US dollar are fiat currencies; they have value because society collectively deems it so. But if the government can print its own money, why do they need your tax dollars? The truth is that they don’t, but because taxes can only be paid in that currency it creates a demand for that currency and thus adds to its value. If the government requires additional money for policy purposes, it can simply order that money be printed and then spend it rather than waiting on tax revenue or borrowing.

There is obviously a concern about inflation with this idea. Most people are aware of cases where runaway inflation can seriously harm an economy; Germany in the 1920s experienced hyperinflation where wheelbarrows full of cash were needed to buy inexpensive items, and more recently Venezuela experienced hyperinflation. If you print too much money too fast, the value of the currency can fall, and prices will go up. But MMT suggests that inflation can be controlled through taxation. When the government increases taxes, it can withdraw that currency from circulation and thus stem inflation. However, the aim should be to create money to invest in the economy to allow the efficient use of its resources and ensure that demand does not outpace the economy itself; this is also a way to check inflation.

My aim here is not to defend MMT, but to recognize its potential for significant, ethically-salient consequences. The most pressing issue right now is the potential that MMT offers. As noted, governments are currently spending record-setting deficits to cover the costs of COVID and to help stimulate growth from the recession it has created. Billions of dollars could be funneled into programs ranging from infrastructure development, to a universal basic income, to funding a Green New Deal. There are seriously ethically-beneficial possibilities. This is why several journalists and experts have suggested that the COVID crisis should make us seriously consider pursuing such policies. Another important factor to consider is that following a traditional monetary understanding, governments may be taking on billions of unnecessary debt that will inhibit future government capabilities for future generations.

On the other hand, there is risk that under MMT there may arise a situation where inflation begins to increase during recession or recovery when raising taxes would be a bad idea. But quantitative easing practices and massive spending have not produced inflation. In fact, central banks are currently looking to increase inflation anyways. However, there is a more significant concern that is highlighted in both the traditional monetary understanding and MMT: the relationship to values and democracy.

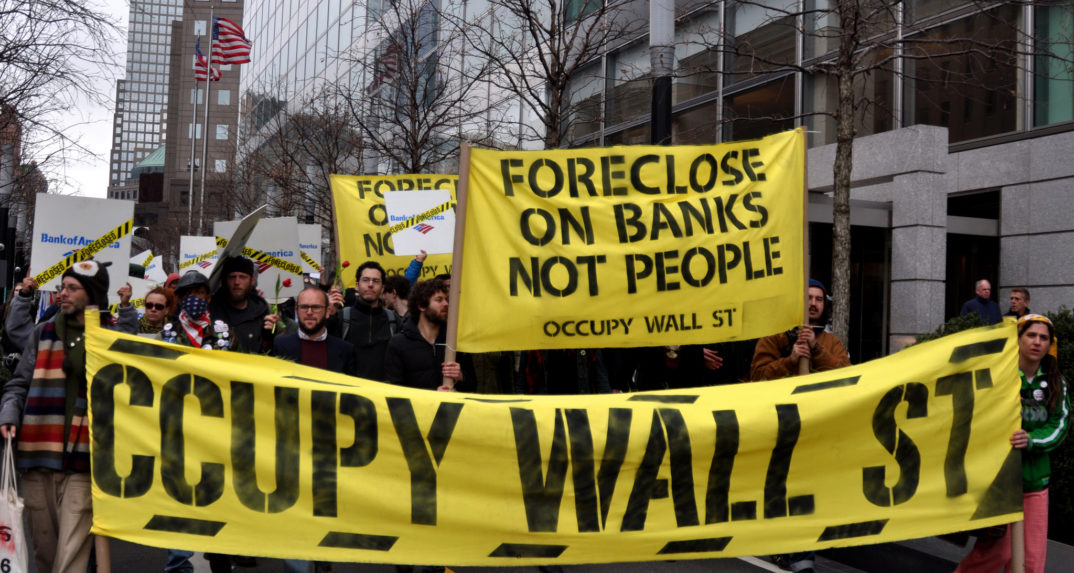

Critics of MMT frequently complain that it would essentially break down the wall that has been erected between central banks and elected governments. According to a recent article evaluating the merits of MMT during COVID, “serious problems may arise from putting the power to create, allocate, and spend money permanently in the hands of politically elected governments.” Governments, critics allege, have shifty politicians who only want to promise the moon in return for votes. While the general statement may be true according to a statistical bell curve, it is still a rather vague criticism. More importantly, in a democratic nation, if the public wanted to send itself knowingly into inflation, should it not be allowed to if it so wished? The myth that you can separate politics from central banking is inherently absurd when in practice it is undemocratic or resistant to democratic reform. There is also the fact that this independence has already been reduced after the 2008 recession anyways.

On the other hand, MMT, while theoretically bringing a democratic influence to central banking, may serve to undermine democracy. Voting and taxation have been closely intertwined concepts. America famously rejected taxation without political representation. The concept of paying taxes in return for government services is also important as it is often preached that paying taxes is an important civic duty; we pay taxes to ensure our mutual security and benefits. Much of the rhetoric about government accountability revolves around making sure that politicians spend tax money appropriately. How much of our thinking about government spending and accountability changes once governments can basically say, “We don’t need your tax dollars”?

Governments wouldn’t really need a budget either as they are currently understood. There would be no deficit. While there would be detailed accounting, governmental budgets would effectively be a spending plan rather than a balance sheet. It could seriously challenge, undermine, stress, and maybe improve several democratic norms and traditions. Given that some have argued that the US government is already effectively following MMT, the political questions are going to take on a newfound importance.