Content mediation platforms are some of the most powerful tools in the world. They control the flow of global news and information, with the ability to silence world leaders like the President of the United States or the President of Brazil. Since these websites have worldwide reach, the owners of these sites do as well; this gives them reach that allows them to, for instance, move money markets overnight. There is evidence to believe that these websites hold the emotions of their users in the palm of their hands. And these websites generate profit on an unimaginable level based on user behavioral data.

Everyone knows that with great power comes great responsibility. Yet, on content mediation platforms, sites like X, Facebook, Bluesky, and Google, users are told they own their content (see their terms of service: X, Facebook, Bluesky, Google). In the same breath, these platforms give themselves the right to use, profit from, alter, and destroy that very content while also avoiding taking moral and legal responsibility for the content.

There is an obvious asymmetry between power and responsibility here, and, in the spirit of holding a critical eye towards powerful entities, we should take a closer look at this.

It is widely known that these “free” internet services generate profit from advertising and data collection. So while they are free to use, users pay through their participation in a massive data collection operation. One necessary component in this economic equation is user-generated content. Without user-generated content, no one would use sites like X, Reddit, Facebook, YouTube, or TikTok. The content that users create and post draws attention. The attention that a platform can command attracts the interest of advertisers who pay for that attention. Meanwhile, every interaction along the way is recorded and used to reinforce algorithmic prediction and monetization to keep the cycle going.

The question we should ask is simple: If user generated content is the key to a company’s economic success, why do we allow them to claim credit in the form of profit and social power, but refuse burden in the form of legal liability and moral responsibility?

There is legal precedent that provides part of the answer to this question. If companies were seen as the owners of the content posted by its millions (and in some cases billions) of users, there would be countless possible cases against them that would ultimately cripple their ability to function at the scale they currently operate at. It is hard to imagine the internet as we know it today if companies that mediated content and information were also held legally liable for everything that is posted on their website.

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act gives interactive computer service companies (e.g., social media companies) broad immunity from content posted by a third party and gives them permission to censor information in good faith. The law establishes a distinction between a company like Facebook or X and that of The New York Times. The former companies are not seen as publishers and therefore are not held accountable for the content posted on their platform; whereas The New York Times is a publisher which gives them obligations that social media companies do not have.

But we should still ask: why shouldn’t social media companies be responsible for what is posted on their website? Why does it matter that this would radically reshape the internet? If companies could not scale up to the order of hosting content posted by hundreds of millions of people, would that be so bad?

One could argue that this would stifle the free flow of information and speech on the internet. Social media companies could no longer claim to be neutral platforms and would become publishers of ordinary people’s speech. However, this could open up the possibility for another kind of internet: a decentralized, diverse, and abundant online ecosystem with a larger number of communities. The status quo seems to assume that free speech requires centralized spaces on the internet where the majority congregate. But, why should free speech require this centralization?

Let us set aside predictions about what the internet would like if companies were held accountable and shift our focus to some conceptual asymmetries that deserve scrutiny.

Ownership, both legally and philosophically, typically entails a bundle of rights that often include the right to use, profit, destroy, and exclude. Platforms reserve the right to do all of these in some respect, other than exclude (since creators can always post elsewhere). However, in the unlikely scenario where a creator posts the only copy of a piece of content on a platform and the platform decides to remove this content, they could in theory exclude use of this content through its destruction. Thus, platforms can act as de facto owners.

These companies claim most of the economic benefit of ownership and, according to their ToS, can use, modify, and destroy content posted on their website in perpetuity, on known technology, as well as not yet invented future technology. This allowance is beginning to create new controversy as generative AI use cases are being scrutinized.

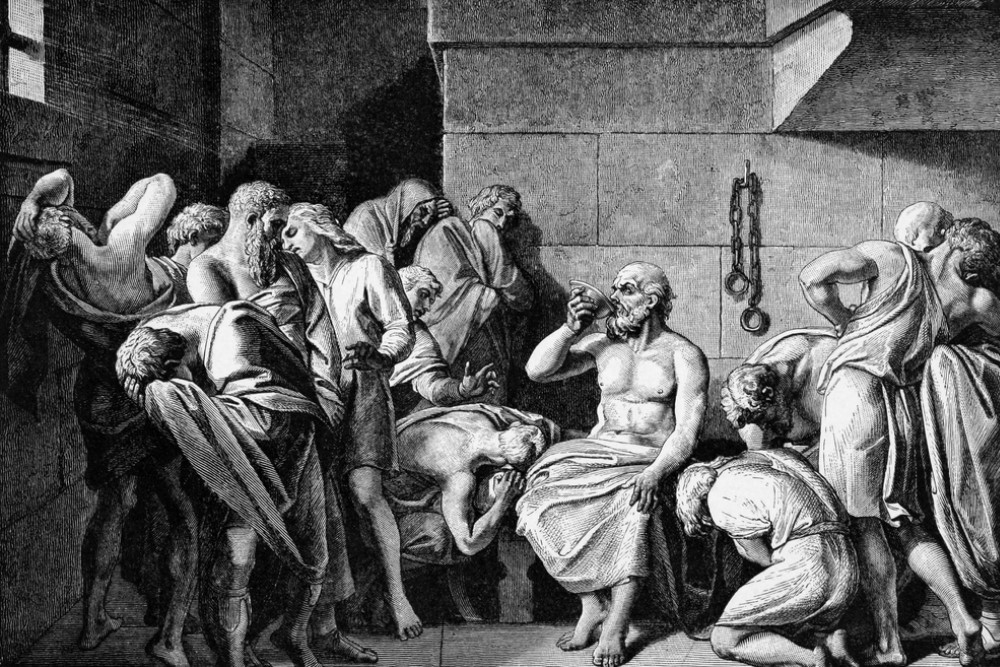

If companies receive most of the benefits of ownership, it would be conceptually symmetrical for them to receive most of the burdens. Figuring out the proportional relationship between benefit and burden is a difficult task, but we can start with an easier question: Are platforms taking on even a minimally acceptable amount of responsibility?

We need not look to first principles or objective standards to answer this question. We already know how these companies view themselves relative to the content they host: they explicitly claim that they are not owners and bear no responsibility for the legal or moral nature of the content they host. If a plausible minimum responsibility is some amount above zero, then it seems that most companies are doing their best to avoid even that.

This concern is moral. Platforms monetize engagement. Engagement is often driven by controversial, inflammatory, and harmful content. Insofar as “bad” content (immoral, unlawful, or untruthful) drives traffic and profits, the moral question cannot be ignored: Why are platforms seen as the appropriate recipients of reward for the engagement driven by both good and bad content (e.g., in the form of profit, influence, and power), without being seeing as the appropriate recipients of blame for that same content (e.g., in the form of liability and moral responsibility)?

While it is easy to suggest these companies take on more liability and moral responsibility, it is much harder to understand what form that responsibility should take. Let me offer two ideas that, while imperfect, gesture towards some possible implementations. First, we could compel companies to acknowledge the fact that they are not neutral conduits of raw information, contrary to what they sometimes like to tell us. We could also demand that they, at the very least, remove categorical claims that establish the sole moral and legal responsibility lies with the users who post the content.

Second, we could borrow legal terminology from copyright law and devise a vicarious liability policy that better acknowledges the financial role that all content, both good and bad, has for content mediation companies. For instance, if a video that gains millions of views turns out to contain illegal content or content that violates the ToS of a website and gets removed, we could come up with a reasonable approximation for how much revenue this video helped create for the company. Asking a company to return the money generated from illegally posted content seems analogous to reclaiming profits made on stolen goods, and does not seem like a widely outrageous demand.

Of course, one might argue that not every case of deserving credit entails deserving blame. For instance, a lifeguard may deserve praise for saving a life but not deserve blame for failing to save a life. However, there is a distinction between the lifeguard and the social media website; the lifeguard did not contribute to the perils of the swimmer, whereas it is arguable that social media websites do contribute to harms in society.

To give just a few examples of this harm, Jonathan Haidt has argued that the rise of social media platforms is causally linked to a rise in anxiety and depression (especially amongst teens). In 2022, Amnesty International made the case that Facebook’s algorithms substantially contributed to violence and discrimination against the Rohingya people in Myanmar. And in her 2024 book Invisible Rulers: The People Who Turn Lies into Reality, Renée DiResta makes a convincing case for why sites like Facebook contribute to the proliferation of conspiracy theorists and sites like X contribute to the formation of online mobs, both of which can contribute to real, offline harm.

As the World Wide Web evolves, we are seeing an increase in wealth disparity and power grow as a result. Ultra-wealthy technocrats have influence over politics and have a deep canyon of resources to pull from to avoid accountability when they face pressure. While it is no small task to regulate the internet while simultaneously keeping it free from unjust censorship, it is imperative to continue looking critically at these asymmetries in power, profit, and responsibility, and ask ourselves: is this the internet we want?