This piece is part of an Under Discussion series. To read more about this week’s topic and see more pieces from this series visit Under Discussion: “Woke Capitalism.”

In response to Walmart’s roll out of new Juneteenth party supplies, wine, and themed ice cream, among other offerings (including a “Congrats Officer” police banner labeled as Juneteenth Day Party Decorations), prominent Black activists and comedians on Twitter, TikTok, and other social media platforms critiqued the corporation for failing to understand the actual values the holiday represents.

From Walmart’s trademark of the word “Juneteenth” to the promotion of its own branded Juneteenth ice-cream instead of a Black-owned ice cream brand with the same flavor, the company’s effort to bring in Black dollars read as tone deaf. Beyond the problems with the products themselves, Twitter users pointed out the general meaninglessness of corporate pandering when larger issues of oppression are still unaddressed.

What should we ultimately expect from influential companies like Walmart? Better products? Donations to just causes? More diverse representation within corporations? And, what is the role of activism targeted at corporations as it relates to larger projects of liberation?

Let’s start with the first set of questions: What should we expect from corporations? It seems that the primary issue in the Juneteenth merch case is that there is a disconnect between the company’s values and the buyers’ values. Whether Walmart made a good-faith effort to embody the values of Juneteenth or just attempted to maximize profit, the company failed to understand the values behind Black liberatory projects and the holiday itself.

One thing that we could expect from corporations is better products. Representation in product choice is important — when things are made for you with an understanding of your needs and expectations, it can improve quality of life and help you feel seen. But products alone are rarely the focus of our liberatory projects. What else might we expect companies to change?

We can also expect corporations to hire a diverse team of workers throughout all levels of the company. This helps to ensure not only fair equality of opportunity, such that anyone of any race, gender, or other social position can come to hold power within the company, but also good product design, because there will be multiple perspectives to influence the process. Walmart still has work to do in this regard, as Black employees are overrepresented in lower wage positions and underrepresented in higher wage positions.

However, diversity in corporate positions of power isn’t enough. If the lowest paid workers in a company make up the greatest share of workers and aren’t paid enough to live on, then we have simply created new hierarchies of inequality and injustice.

Corporate diversity, without fair wages, only liberates a select number of people (and those who make it into the halls of power often find them hostile to the historically marginalized).

It seems that better representation demands, in part, the material and social conditions for people of all different backgrounds to be able to live and flourish. For instance, a company should not merely hire disabled people and expect them to conform to company expectations without accommodation — the physical and organizational structures of the company should be rebuilt to allow those employees to carry out their jobs well.

This holds true at the level of corporate donations. We often expect corporations to donate to just causes and critique them when they don’t, but there are also unfortunate power differentials that arise when the corporate elite can hoard money to donate to political goals instead of paying their workers a fair wage that would allow them to donate to causes they care about. In the age in which money is speech, surely this is not what we want our representative democracy to look like.

The main issue with our discussions around woke capitalism is not any of the individual critiques: it’s the big-picture strategy. What seems to be happening in our collective discourse is that we get caught up in easily Twitter-izable consumer issues that companies will quickly respond to in order to avoid a social media backlash. Even at the level of corporate diversity, it’s much easier to put a few Black employees in positions of power than to ensure a living wage for all employees.

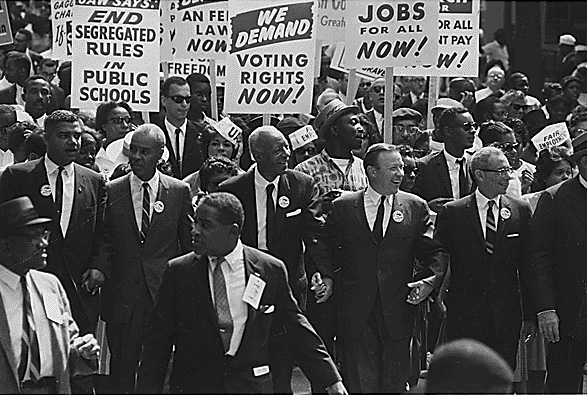

In some ways, the “woke capitalism” battle between conservative and liberal forces is the easier battle to win, and so we get stuck in these proxy wars for the harder work of systemic change to address inequalities compounded by history and multiple intersecting oppressions.

Instead of focusing our efforts into getting companies to respond to issues regarding product design, representation, and charitable donations, it would serve us better to treat these as issues that arise from the same central problem: class-based inequities that are built upon white supremacy and that disproportionally impact marginalized groups.

If we can shift our energy to the more difficult battles of ensuring that companies make the material and organizational changes for workers to have a good quality of life and that our broader social and legal structures are made more just, our victories will be more meaningful. We will ultimately have a greater impact, even if, on the whole, we have more failures at the level of responding to bad product design.

Black activists understand this point well. The Walmart social media outcry and subsequent apology happened over a relatively short period of time, and it represents a small (though not inconsequential) piece in a much larger project of policing and prison reform, affordable housing and fair wage fights, and other efforts to celebrate Black freedom and joy. Unfortunately, our collective discourse tends to highlight these shorter-term projects and hide the longer and more difficult labors of organizing. So long as we, especially as allies, remember to engage in and contribute to these larger projects of liberation, there is no problem in using consumer activism to promote better corporate practices. We just need to understand the limits of that approach.