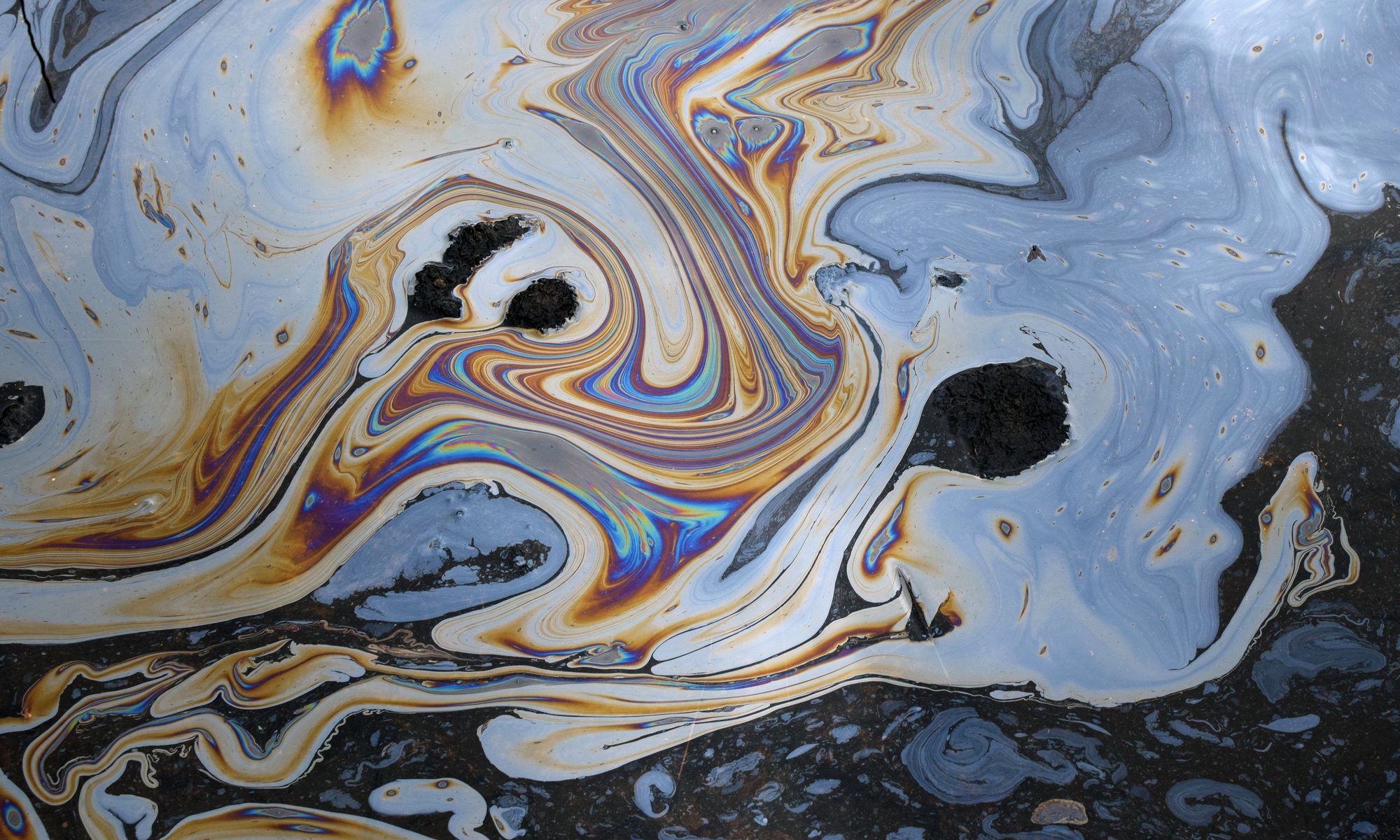

In a May 25th decision, Sackett v. Environmental Protections Agency, the U.S. Supreme Court placed further restrictions on the regulatory powers of the federal government. It has been longstanding practice that under the Clean Water Act the Environmental Protection Agency can regulate wetlands connected to navigable waters. But the recent 5-4 decision now requires “continuous surface connections” between regulatable wetlands and navigable waters, disregarding groundwater pathways.

This is obviously a victory for industries most likely to pollute waters – mining, construction, ranching, etc. – but more broadly it highlights the separation between two very different legal regimes. One governs the actions of corporations and white-collar through administrative agencies, regulations, and fines. The other involves the more familiar legal regime of cops, imprisonment, and even executions.

Criminal prosecution for harms such as pollution does occur, but is generally of a lesser order. The most severe penalty under the Clean Water Act is “knowing endangerment” – if, for example, a business owner ordered deadly chemical waste dumped in a river they knew was used as drinking water. The maximum penalty for knowing endangerment is 15 years in prison and a $250,000 fine.

But is polluting a river, with chemicals possessing the power to kill someone, a lesser crime than murder? (Even if one generally rebukes the American criminal justice system, the inconsistency can be an independent concern.) Should we, if we strive to be consistent in matters of justice, allow for harsher penalties?

One way to think about what severity of punishment would be justifiable is via theories of punishment. These attempt to justify the use of punishment in society. The two most common justifications deployed are consequentialist or retributivist.

Consequentialist theories of punishment – namely deterrence, incapacitation, and rehabilitation – justify punishment as a means of achieving specific social aims. Deterrence theories justify punishment on the basis of discouraging further crimes. Incapacitation theories argue punishment is justified to remove harmful elements from society. Rehabilitation theories explain punishment as a process to reform the criminal and reintegrate them in society. As the aim of consequentialist theories is to produce certain outcomes, the form of punishment depends on the most effective means for achieving the social goal.

Take deterrence as an example. It is sometimes assumed a harsher punishment is a stronger deterrent, but evidence indicates the primary deterrent is often the likelihood of being caught. Therefore even for very serious crimes a staunch deterrence theorist may not care how severe the punishment is, as long as it is rigorously enforced (which, incidentally, seems not to be the case with environmental crimes).

Retributivism is the approach to punishment where questions of proportionality between crimes and their punishments is most significant. It is also the dominant theory in the American legal system. The idea behind retributivism is not to achieve a specific social good or prevent harm, but ensure criminals get what they deserve. This has enormous psychological appeal, although philosophers have struggled to establish a clear basis for the intuition that crimes “deserve” punishment. What exactly does it mean for punishment to “fit” the crime?

Retributivism often holds that punishments should be fair or proportionate. Tax fraud, for example, probably shouldn’t merit death. But does this suggest there are retributivist grounds for claiming crimes like assault, mugging, or murder deserve a harsher punishment than knowingly disposing of toxic chemicals in a river used for drinking? It may depend on the exact details of the harm caused. We generally punish murder more severely than assault, and assault more seriously than shoplifting. On this analysis, large-scale crimes such as polluting a river should have extremely severe punishments. For more distant harms, say a cancer diagnosis 10 years after the disposal of chemical waste, it may be challenging to tie the crime to the particular harm. But this is a prosecutorial challenge and does not concern what punishment is in principle deserved.

What about violence? Violent crimes are often distinguished from non-violent crimes, with violent crimes meriting harsher sentencing. Is a crime like dumping toxic waste in a river less severe because it is less violent? One challenge to this is that violence is often simply a proxy for harm caused, where bodily harm is treated as more severe than, say, monetary loss. But environmental crimes can cause bodily harm. Presumably poisoning someone to death is not a lesser crime than stabbing someone to death, even if it is nonviolent.

A further question is whether harms “add up.” Is stealing 100 dollars from 100,000 people worse than murdering one person? If harms compound in any way, then crimes with very widespread effect, such as environmental crimes, high-level political corruption, and financial crimes, could be among the most severe of all crimes even if their per-person impact is small.

As for arguments in favor of less severe sentencing for crimes such as pollution, perhaps the best defense concerns intent. When someone engages in financial shenanigans or dumps toxic waste in a river, their intent in most cases is not, presumably, to cause harm. By contrast, with a murder or assault the harm is often the central aim. The question that emerges is whether callous indifference to the harm caused is preferable to intentionally seeking to cause harm. Such judgments are hard to make, but even if preferable to an overt intent to harm, indifference to harming others is not a particularly exculpatory state of mind.

There is also a notable inconsistency here. In the United States there exists the practice of felony murder, where if someone dies during the course of a felony (e.g., a robbery), the defendant can also be charged with murder. For example, a lookout in a robbery was charged with murder after cops responding to the robbery accidentally killed someone. This practice is unsurprisingly controversial, but if it exists for crimes like robbery where there was no intent to kill, then it should logically exist for dangerous environmental crimes as well.

Overall, the retributive case for lesser punishment for environmental crimes is not compelling. If anything, on a retributive analysis, the punishments for large-scale crimes should be exceptionally severe. Beyond philosophical analysis, there are two other plausible explanations for asymmetries in crime and punishment.

First, our sense of justice thrives on the visceral. We are shocked at crimes of singular brutality and cruelty with identifiable (and sympathetic) victims. It is well established that we can quickly go numb to widescale harms. And yet, our society is dominated by large institutions. And it is those ensconced in the upper echelons of these institutions who have the most capacity to cause harm, even if they are very far removed from the consequences. The obfuscation of climate change by fossil fuel companies is the biggest, although far from the only, example. We psychologically struggle with more abstract crime with more diffuse consequences.

Second, is the unequal distribution of power in society. It is in the interest of the mugger to have minimal sentences for mugging and the coal executive to have minimal sentences for polluting. But there is a vast difference in their ability to shape the law.

Together, these two considerations often confound what should otherwise be a more straightforward question.