According to Amazon lore, Jeff Bezos abandoned a cushy hedge fund job after reading The Remains of the Day, Kuzuo Ishiguro’s melancholy tale of wasted energy and missed opportunities. The young entrepreneur was so moved by the novel that he committed to a life of “regret minimization,” and struck out on his own to start a small online bookstore. Bezos’ then-wife claims that he didn’t pick up Ishiguro until after he started Amazon, but it still makes for a potent founding myth. Though Amazon’s virtual marketplace now offers far more than books, the nascent mega-corporation was influenced by literature on a fundamental level, and perhaps, for better or for worse, it has come to influence literature in turn.

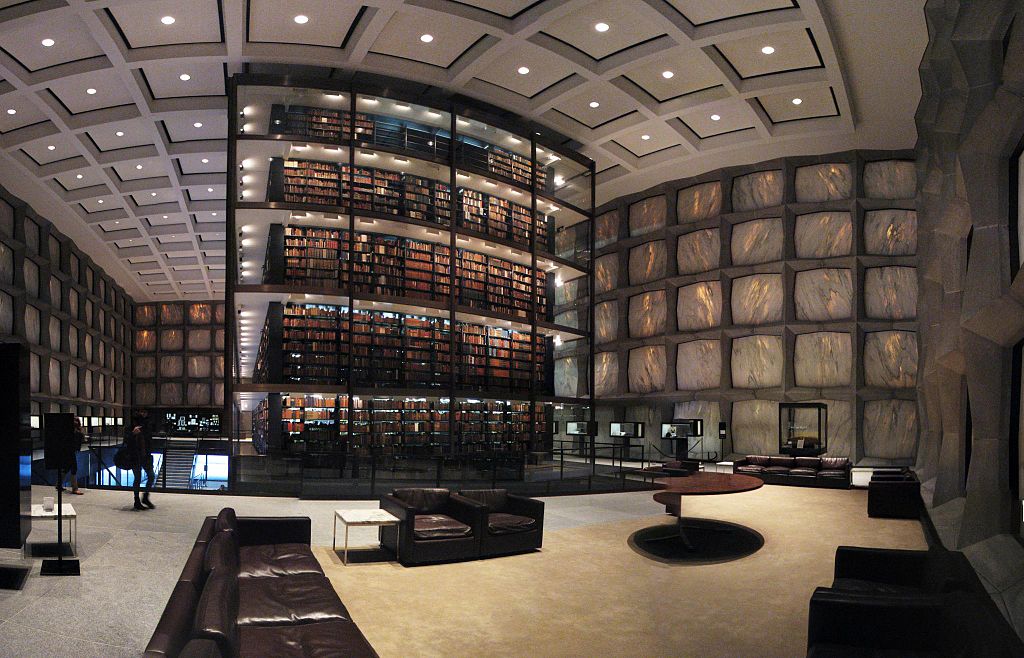

Mark McGurl, a literary critic who teaches at Stanford, traces the influence of Amazon on the fiction marketplace in his new book, Everything and Less: The Novel in the Age of Amazon. McGurl sees Amazon as a black hole with an inescapable gravitational pull, sucking everything from highbrow metafiction to niche erotica into its dark maw. He makes the bold claim that “The rise of Amazon is the most significant novelty in recent literary history, representing an attempt to reforge contemporary literary life as an adjunct to online retail.” Every book is neatly codified by genre (often incorrectly) and plugged into Amazon’s labyrinthine algorithm, where they become commodities rather than texts. “As a literary institution,” he writes, Amazon “is the obverse of the writing program, facilitating commerce in the raw.” In other words, online retailers nakedly prioritize the market over artistic individuality, which ultimately homogenizes the literary landscape. McGurl acknowledges that Amazon has democratized self-publishing, in-so-far as it’s possible for Amazon to democratize anything. Through Kindle Direct Publishing, Amazon pays hundreds of millions of dollars a year to authors around the globe, and though few writers make enough to support themselves through the platform, we have never been more inundated with things to read.

McGurl’s argument does have some weak spots. For example, Kyle Chaka objects that McGurl “doesn’t present any evidence that Amazon’s algorithm incentivizes novelists like Knausgaard or Ben Lerner to write in a certain style, or that it even accounts for their popularity, relative to other, lesser-known contemporary novelists.” If the argument is that Amazon has changed every aspect of literary production, shouldn’t we be able to see that impact in the style and form of bestselling novels? McGurl also oversimplifies the broad range of stories that Amazon promotes. He believes that all commodified fiction can be categorized in one of two ways. A story is an “epic” if it takes a cosmic perspective on life, uplifts the human spirit, and creates (in McGurl’s words) a sense of “cultural integration.” Alternatively, “romance” stories involve interpersonal drama, intimate worlds, and soothe us rather than puff us up. These categories flatten the diverse array of fiction published by Amazon and its subsidiaries, and how can we be sure that the company created our desire to be soothed or aggrandized? They’ve certainly profited off such desires, but there isn’t evidence that we’re increasingly relying on these narrative models or that Amazon alone is driving that change.

Amazon certainly is a problem for literature, but as Chaka points out, the problem has more to do with business than genre trends. Amazon’s low prices endanger small bookstores and the traditional publishing houses that stock their shelves. When negotiating contracts with independent publishers in the early 2000’s, Bezos advised his company to “approach these small publishers the way a cheetah would pursue a sickly gazelle.” This predatory attitude towards traditional marketplaces has hardly changed, and does affect the literary landscape in tangible ways. Whether the democratization of online publishing has come at the expense of traditional publishing is difficult to say, and it’s even more difficult to determine whether or not this is necessarily a bad thing, given how extremely homogeneous the publishing industry is.

Beyond the publishing industry, it might be said that Amazon poses an existential threat to writers. When so much content is available online, and millions of writers are forced to compete for the public’s attention and money, is there a point in writing at all? Parul Sehgal notes “a certain miasma of shame that emanates from much contemporary fiction,” even fiction produced by successful and well-known authors, and wonders if this despair arises from the online marketplace Amazon has created. Given the general mood of self-doubt and ennui, it’s worth celebrating how many people continue to be creative without hope of material reward. Amazon can hardly take credit for the vast output of such writers, but if Amazon has altered the way we approach and consume fiction, they certainly haven’t crushed the creative impulse.