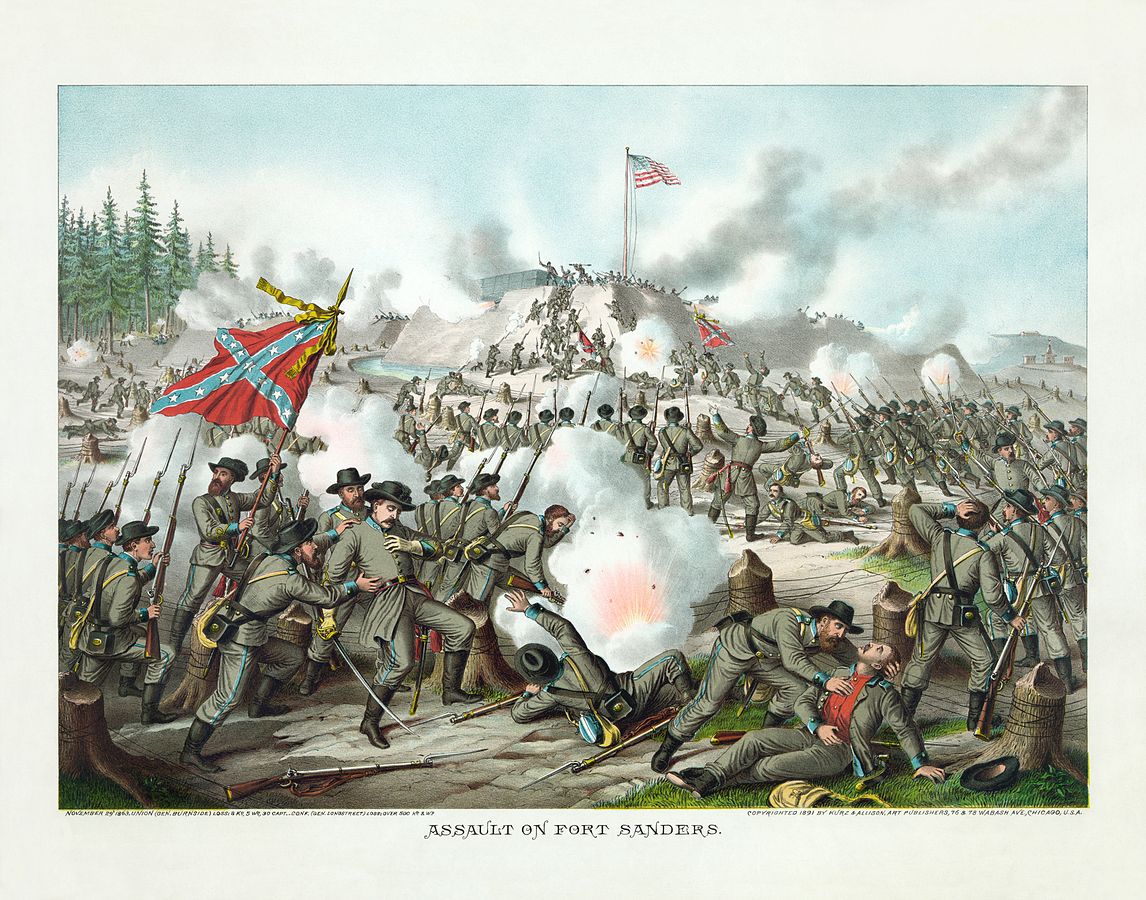

Is it right to condemn historical figures for moral beliefs that, while common during their time, are now known to be odious?

Our attitudes toward historical figures matter. Our attitudes bear on the question of what public honors should be bestowed on morally flawed historical figures, and our attitudes toward historical figures will influence our contemporary moral thinking. How I view historical figures may influence my trust in moral and institutional traditions I have received from those thinkers. If I believe our Founding Fathers were good and noble people with certain, though largely isolatable, tragic flaws, I’ll trust our constitutional system more than if I believe our Founding Fathers were mostly moral degenerates skilled at couching their corruption in the propagandistic rhetoric of admirable ideals. This trust need not be self-conscious. If you present multiple people with the exact same policy proposals while varying who you say supports it, you can flip who supports which policy. Just seeing an idea as presented by someone ‘on my side’ or ‘in my team’ or ‘within my in-group’ (to use the language of social psychology), will incline you to find it plausible. The extent to which I’ll instinctively trust the political structure set up by our Founding Fathers will depend, at least in part, on the extent to which I see the Founding Fathers as patriotic exemplars.

So how should we think of historical figures with odious beliefs? There are two lines of argument against judging them the way we would judge contemporaries.

The first line is often expressed by language like “they belonged to a particular time.” The argument suggests that these thinkers were, because of their historical context, blamelessly morally ignorant of things we now know.

If you heard about a doctor who, in their rush to treat patients as quickly as possible, did not bother to sterilize materials between amputations, you would reasonably condemn that person as culpably negligent or heartless. However, we do not make similar moral judgements about doctors in the seventeenth century. Sure, it would have been better had they sterilized their instruments, but these doctors did not have the germ theory of disease, they had no reason to think that boiling their surgical instruments would do anything, and indeed they had every reason to think that the longer they took to perform amputations the further infections could spread.

We do not judge historical figures for terrible surgical practices because we think that at least some forms of non-moral ignorance exculpate. But if non-moral ignorance can exculpate, can’t moral ignorance as well? Just as we, the beneficiaries of the modern medical awakening, cannot fairly judge historical figures for the poor choices they made as a consequence of their worse scientific environment, so, the thought goes, we, the beneficiaries of various moral awakenings, cannot fairly judge historical figures for the poor choices they made as a consequence of their worse moral environment.

There are, however, good reasons to doubt the extrapolation from the non-moral case to the moral case. One contemporary philosopher who argues for an asymmetry between moral and non-moral ignorance is Elizabeth Harman. Harman, following Nomy Arpaly, thinks you are blameworthy if you betray an inadequate concern for what is morally significant.

This account would explain why non-moral ignorance sometimes excuses. If I mistakenly believe a certain charitable organization does good work, then donating to that actually harmful charity need not display an inadequate concern for the plight of the poor, for example. I might really care as much as I should for justice, but simply be misled about what would best serve others.

This account of blameworthiness would also explain why moral ignorance does not excuse. If I’m morally ignorant that I ought to give to the poor, then that very ignorance displays a lack of concern for the poor, and thus a lack of concern for what really is morally significant. Circumstances where we fail to grasp the character of our acts (say I thought the backpack I grabbed on my way out of class was mine, when really it was your very similar-looking bag) do not communicate moral indifference (I may still be fully concerned to respect your property). In contrast, being aware that I was taking your property but not appreciating that it was wrong, would actually prove my lack of concern.

But not all philosophers agree with drawing this strong asymmetry between moral and non-moral ignorance. Why, for instance, is it wrong for us to morally condemn vicious people raised as child soldiers? One plausible answer is that child soldiers cannot be blamed for their ignorance of the moral law.

Of course, even if we accept moral ignorance can, in principle, excuse, it remains an open question if it does in the historical cases we’re considering. There is a difference between having had one’s conscience systematically flayed by the brutal brainwashing that goes into creating a child soldier, and simply growing up in a society with a high tolerance for evil.

Consider the view of Elizabeth Anscombe, who thinks there are some examples of moral ignorance that really do excuse. Anscombe describes an executioner who has private knowledge of a condemned man’s innocence, but who cannot use that knowledge to exonerate the man. She asks us to further suppose the executioner knows the man had a fair trial under a rightful legal authority. Anscombe thinks since the greatest moral theologians can’t agree about this case, the simple executioner might really be blameless for choosing wrongly.

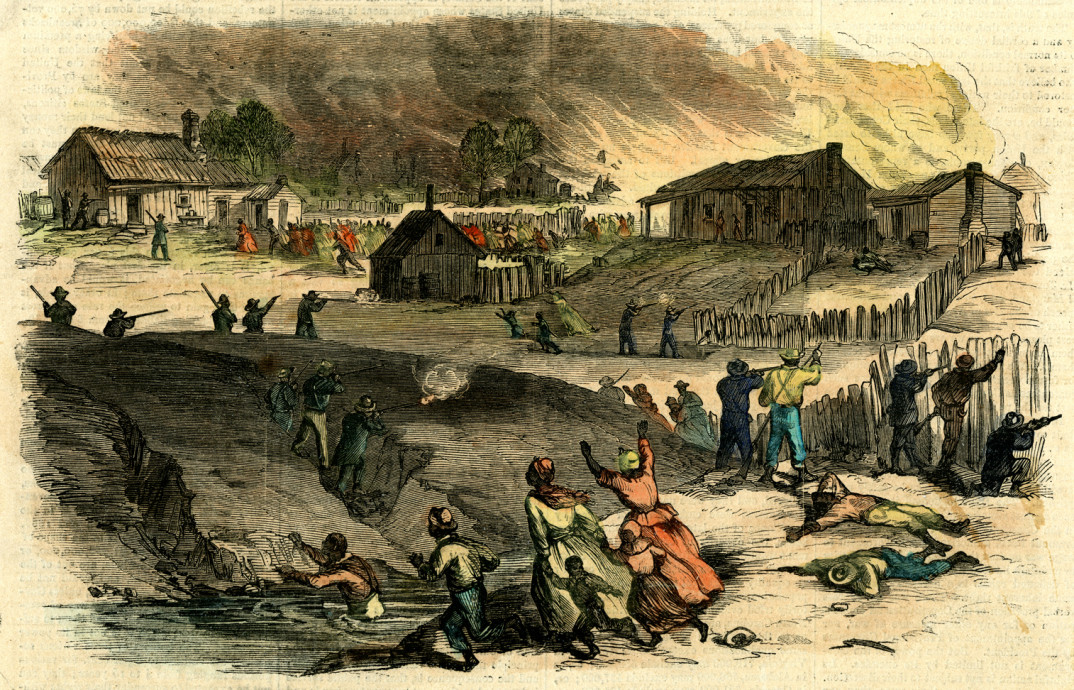

But even if there are cases of excusing moral ignorance, Anscombe thinks they are exceedingly rare. They don’t cover the controversial cases of historical figures. Anscombe follows Aristotle and Aquinas in thinking that the main outlines of morality are accessible by the light of natural human reason, and while humans are incredibly self-deceived, that does not get us off the hook given that we should, and can, almost always know the core of what is right or wrong if we don’t give into vicious self-deception. Their actions betrayed ignorance of basic moral truths which Anscombe thinks were clearly accessible to them. Thus, Anscombe ends up thinking that while there is no principled asymmetry between moral and non-moral ignorance, there is a practical asymmetry. The main outlines of science (say germ theory) are not truths available to everyone just in light of common human reason, but the main outlines of morality (say the evil of chattel slavery) are truths available to everyone just in light of common human reason. Thus, it is far more common for non-moral ignorance to excuse; not because non-moral ignorance alone can excuse, but because moral ignorance is rarely blameless.

Perhaps this first line of argument could be salvaged, but for now I will put it aside, because…

there is a second line of argument I want to consider. This is the argument often expressed by the honest voice in the back of my head saying: “but are you really that confident that if you were a white kid growing up in Antebellum South that you would have had the moral clarity to see the right of things?” Sure, maybe I agree with Anscombe and Aquinas that I should have been able to see the right of things. But am I really so certain I would have?

The force of this thought comes from an extension of the norm against hypocritical blame. We generally think it inappropriate to blame someone for things I expect I might do were I in your situation. Since I’m not particularly exceptional amongst my own moral cohort, I don’t have good reason to think I’d be exceptional if transplanted to a historical cohort, so I should temper my outrage at historical figures.

However, here we tend to draw the wrong lesson. We’re tempted to think something like: I’m a morally decent person, I’m probably not in a position to judge at least many historical figures as far worse than me, so many of these historical figures must not have been that bad.

That is almost the opposite of the conclusion suggested here. We have already seen when considering the first line of argument that there are good reasons for thinking historical figures are fully responsible for their bad beliefs. My hypocrisy does not show the other person is not evil, rather it shows I might be evil as well.

Thoughts on hypocrisy should not lead us to think better of historical figures, but rather to think worse, and more humbly, of ourselves. We should recognize that many of the beliefs about which we are self-righteous might be largely chosen, not from principle, but because it helps us gain the glowing approval of those whose opinions we prize. And likewise, we should perhaps recognize that whatever moral clarity we do have is an undeserved grace.

This does require a pessimistic view of humanity. Yet it is a sort of pessimism shared by many of the great moral traditions and thinkers. Plato thought that our material bodies, filled with appetites, continually pull us away from virtue. Aristotle thought that only someone with an exceptionally fortunate and unearned upbringing could ever become good. Stoics doubted there ever were, or even could be, any true sages. Christians taught humans were slaves to original sin absent the intervention of divine grace. Kant famously proclaimed humans were by nature evil.

If we accept this pessimism, what attitude should we take towards historical figures? On the one hand it allows you to acknowledge the utter evil and depravity of historical figures who defended odious practices. But on the other hand, it also discourages the hatred that inclines us to divide the world into the virtuous in-group and the vicious out-group. We should willingly acknowledge the evil of historical figures, but should be skeptical that it gives us any standing to look down on them, as though we have any moral height from which to condescend.

There are three principled attitudes to take towards historical figures. First, following Harman, we could think there is a real asymmetry between our own blameworthiness and theirs because our differing moral values really show differing levels of blameworthiness. Second, we could see them as similar to ourselves — largely good people though victims of largely blameless ignorance. Or third, and this one seems right to me, we could again see them as similar to ourselves, but as also blameworthy in their ignorance of their own depravity, and so conclude that we are actually closer to their wickedness than we realized.