Canada, despite a rash of democratic, economic, and separation crises, must make a difficult choice with regards to its neighbor to the south. While the United States has, on the one hand, threatened Canada with annexation and is currently attempting to push its industrialized heartland into oblivion, it has also recently offered a new deal with regards to continental defense in the form of the “Golden Dome” proposal. As new technology brings new military threats, concerns about missile and drone defense loom larger than ever before. But what (and who) should Canada be defending itself against? Does it make sense to further integrate Canadian military capabilities with a country that prefers it didn’t exist?

On May 20th, Donald Trump announced planes for the space-based missile defense system known as the “Golden Dome” to protect America from long-range and hypersonic missile threats and from drones. The desire for a missile defense system comes after increasing concerns in recent years about the threat of hypersonic missiles, ballistic missiles, and drones which have proved very effective on the battlefields of Ukraine. Similar in ways to Israel’s iron dome concept, the system would include a huge network of sensors, satellites, and ground-based (and possibly space-based) interceptors to eliminate aerial threats to the North American continent. Following the announcement, Trump said that Canada has been asked to join and that the Canadian government has expressed interest. Given Canada’s reluctance to sign on to similar projects in the past and a rocky relationship with the second Trump administration, one wonders whether Canada should once again reject the proposal or decide to break with tradition.

On the one hand, Canada has good reasons to refuse. As mentioned, Canada has been reluctant to join major missile defense projects in the past. In the early 1960s, the Kennedy administration attempted to get Canada to host nuclear missiles. In the 1980s, the Reagan administration proposed the Strategic Defense Initiative (aka “Star Wars”) which was turned down by Canada. In 2004, the Bush administration proposed another missile defense system which was rejected by Prime Minister Paul Martin. The reasons for these rejections can be complex, but each time the proposal ran counter to Canadian skepticism of military procurement in general and heightened Canadian fears about getting too close militarily to the United States.

Many may not realize that modern Canada is the result of the fact that the American Revolution was more of a civil war than a revolution within a single nation. Modern English Canada is culturally tied to the losing side of that civil war, the loyalists who fled the United States and wished to remain British. While Canadians like Americans, they have always been wary of getting too close or being too American. Meanwhile, the Trump administration threats of annexing Canada as the 51st state have pushed these sentiments into overdrive. If Canada must think of the United States as a potential threat rather than an ally, the prospect of military integration looks problematic.

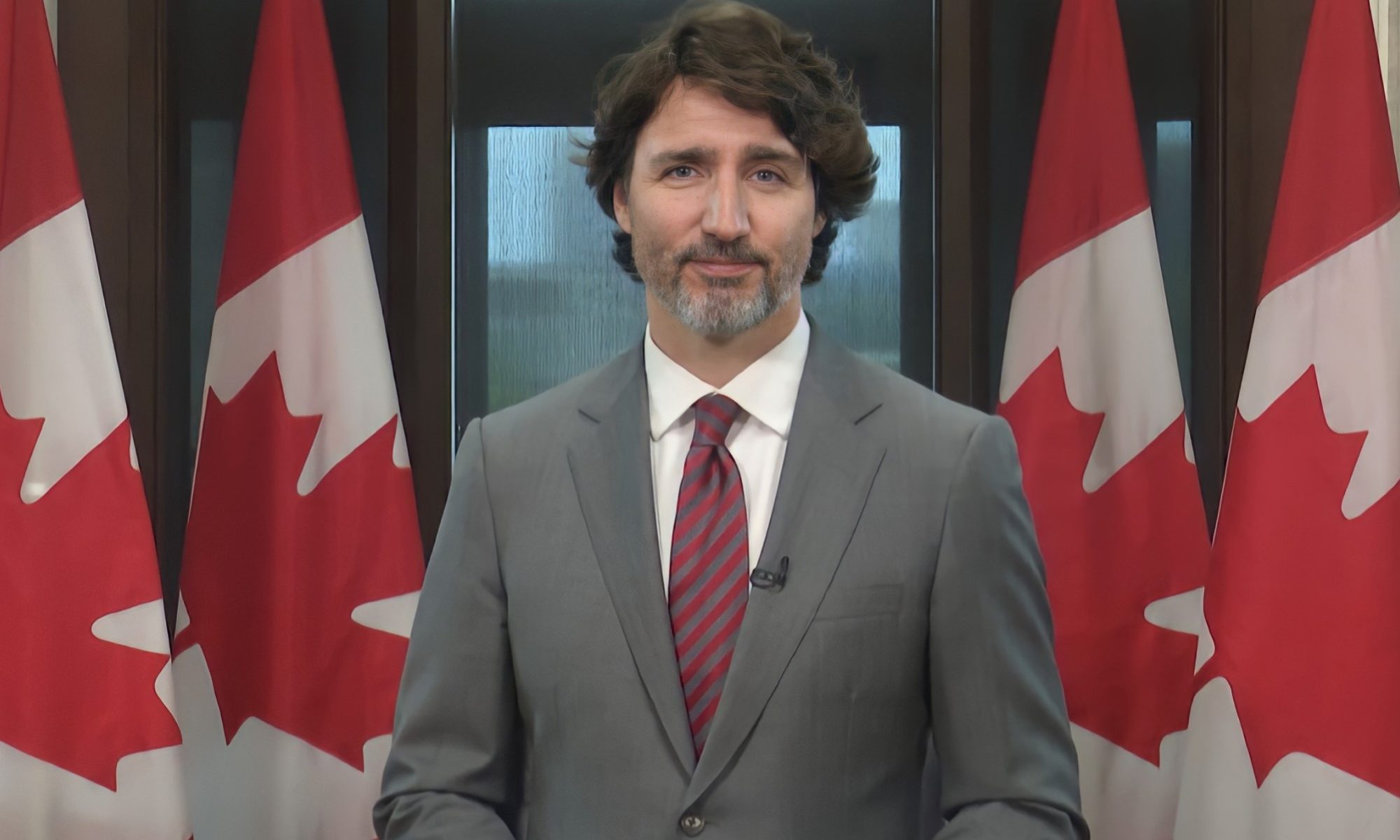

There is also the fact that Canadians are skeptical of large military spending. While the administration has said that the Golden Dome will cost under $200 billion dollars, Space Force has said the costs could be closer to one trillion dollars. Meanwhile, Canada is facing budgetary issues owing to the Trudeau administration’s spending and lack of economic growth, as well as the United States’s recent trade war.

Given this, Canada is in no hurry to invest billions of dollars in American defense contractors. Tariffs have already made Canada consider a pause on its purchase of the F-35 jet after a decade of dragging their feet over the decision to purchase them. Not only are there concerns about giving money to American companies for this, but also the fact that Canada will not control any spare parts or maintenance on the jets. Any support of the Golden Dome project will no doubt haunt Canada should it only benefit the American economy and limit Canada’s ability to make independent defense decisions.

On the other hand, missile and drone threats are increasing, and we are living in an increasingly perilous time. Missile defense would be beneficial for Canada, who is also looking to limit defense spending to 2% of GDP in line with NATO targets. They are also looking to modernize NORAD, the continental air defense system that already includes Canada. Investing in the Golden Dome could not only mean better NORAD integration, but it would also presumably mean that Canada would have a larger voice at the table. Currently, for example, Canadian sensors and radar provide early warning for aerial attack, but Canada is more limited in terms of how to respond to threats without the United States.

There are also political reasons to suggest we might be interested. Given Trump’s unhappiness with Canada’s lack of military defense spending and continued threats to our economy, there’s reason to give the appearance that we are willing to play ball. Despite administration projections, it’s unlikely that the Golden Dome proposal will come to fruition by the time Trump’s time in office ends. Verbal commitments now may not lead to any more concrete investments in the near future.

Not only could joining the Golden Dome project yield some economic and industrial benefits, it may also offer leverage when it comes to other international issues such as Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic and the opening of the Northwest Passage. If the United States wants Canada to host and maintain a bunch of equipment, this may provide greater strategic influence for Canada than if we were to refuse to participate from the start.

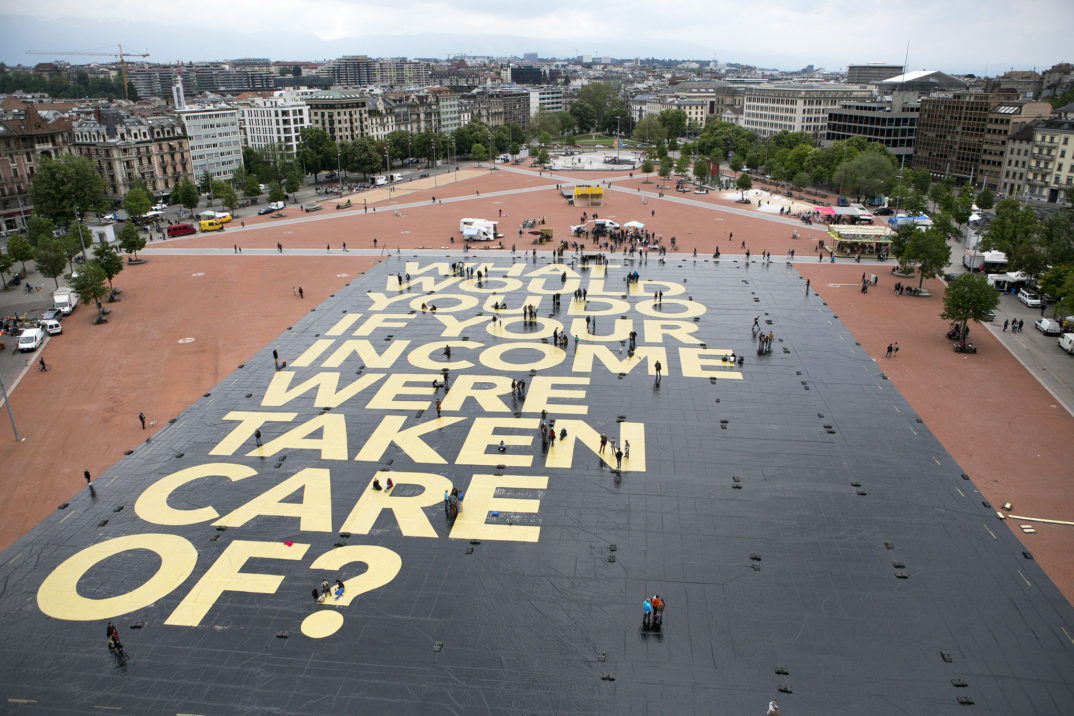

No doubt many Canadians would be happy for a US missile to intercept an attack on a Canadian city, and it isn’t as if there are great options for Canada to develop its own missile defense system – particularly given our skepticism towards military spending. Still, it’s hard to jump into bed with someone who has expressed a desire to annex your country. Not only is it a difficult policy decision, but it is also a difficult political decision as the announcement comes just as Canadians’ views on America have soured. For a Prime Minister who just ran on a campaign of defending Canadian sovereignty (“elbows up” being the popular slogan), it sends a contradictory message to voters to join the Golden Dome initiative. It’s said that moral decisions are not about making easy choices between good and bad, right and wrong, but instead hard choices between competing values and uncertain outcomes. Canada has a difficult decision to make.