In late June the Supreme Court of the United States released a bevy of opinions. Most prominent perhaps is the 5-4 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health in which the court overturned the famous 1973 Roe v. Wade decision. The court also, in Kennedy v. Bremerton, has done away with the long used “Lemon test” concerning the separation of church and state.

Beyond questions of whether the decisions are ethically correct, these rulings are notable because they go against established precedent. In legal systems like the United States, courts generally adhere to the doctrine of stare decisis or “to stand by things decided.” The Supreme Court has previously ruled – in both Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey – that there exists an implicit constitutional right to abortion. Changing its mind is then unusual, although hardly unique to the current court. The 1954 Brown v. Board of Education is famously seen to have overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine the court had previously held in Plessy v. Ferguson. (Although, technically, the Brown ruling is more narrow, only contending that separate but equal does not apply in public schools.) Evan Butts has previously discussed some of the practicalities of overturning precedent for The Prindle Post.

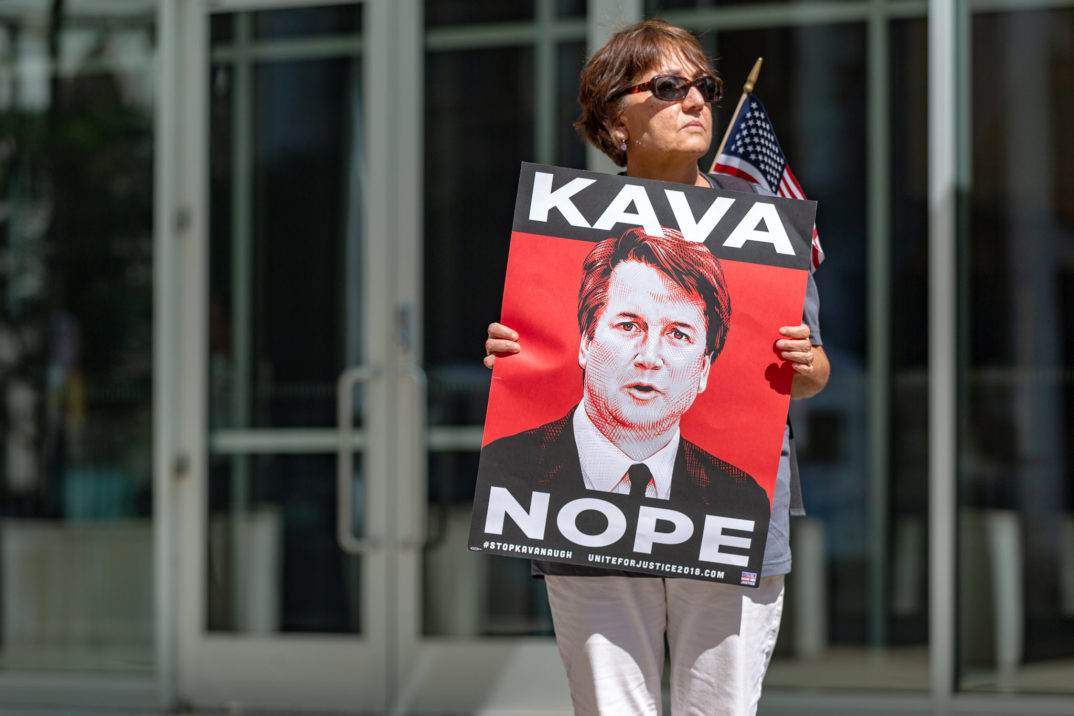

Recent additions to the Supreme Court, such as Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch, are being criticized for implying (misleadingly) they would stick with precedent on rulings like Roe v. Wade.

But why should the Court be bound by past opinion at all? Imagine a scientist claiming that we should stick with Newtonian physics and not jump ship to general relativity because Newtonian physics is an established precedent – even though they agree Newtonianism is incorrect.

This would be preposterous. And yet stare decisis is often understood to imply such a burden, that, as Justice Brandeis wrote in 1932 “in most matters it is more important that the applicable rule of law be settled than it be settled right.”

Following precedent in cases where the rightness of the initial ruling is not in question is straightforward – this is nothing more than a demand for courts to interpret the law correctly. Precedent as such is superfluous here, as consistency is being ensured purely by the court deciding correctly in each case. The doctrine of stare decisis only achieves importance when it comes to ambiguous or even wrongly decided cases, and whether they should nonetheless maintain some hold over future judicial decisions.

As Justice Brandeis suggested, defenders of stare decisis justify it by pointing to its role in settling matters of law – that is, making law fair, consistent, and predictable, as opposed to mercurial.

The claim is that absent this general principle of stability, the law could change drastically with the simple turnover of judges. More practically, precedent also provides courts the legal tools to decide cases efficiently.

The value of having settled law is especially clear in cases like Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) which enshrined a constitutional right to the recognition of same-sex marriages. Agree or disagree ethically, it is clear same-sex couples can and have built their lives differently knowing that they have a right to marriage recognition. Likewise, agree or disagree ethically with abortion, confidence they have control of whether to go through with a pregnancy affects how women live their lives. These are referred to as reliance interests.

Notably, these defenses of precedent contain the seeds of their own limitation as ultimately the doctrine of stare decisis is justified on the basis of being a social good. Cases of pernicious and dubiously-decided law are weighed against the value of the law being settled. Justice Brandeis made a further point, distinguishing the weight of precedent in statutory law (made by the legislature) which can easily be overturned by later legislation, from precedent in matters of constitutional interpretation. According to Brandeis, precedent matters less when there are fewer forms of redress.

Overall, few if any defend an imperative to follow precedent for all cases – at least when it comes to rulings being made by a court of equal or lesser authority. Precedents can and do get overturned. That lower courts should follow upper courts can provide an alternative defense of following precedent even in wrongly decided cases (sometimes called vertical as opposed to horizontal precedent).

In the 2018 5-4 decision Janus v. AFSCME, the majority opinion authored by Justice Samuel Alito indicated that the current Supreme Court is especially open to revisiting previously decided matters when it believes they were wrongly decided. Justice Clarence Thomas has claimed, most recently in his concurring opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, that the Court should correct “demonstrably erroneous” rulings.

Expanding Thomas’s point, one could argue that the Supreme Court should have no special obligation to consider the social value of precedent and settled law at all, and simply always make the legally correct decision.

The chief challenge with this line of argument is on what basis should a case be considered “demonstrably erroneous”? Certainly, the current Supreme Court does not have consensus that the legal reasoning of Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey was wrong. (Brown v. Board of Education incidentally was a unanimous decision.) Absent strong evidence, e.g., a unified court, that a decision was made wrongly on legal grounds, the “demonstrably erroneous” standard of overturning precedent can collapse into “I think this decision was decided wrongly, and therefore I am justified in overruling it.” This reintroduces the dependence on the idiosyncrasies of specific justices that a principle like stare decisis is supposed to help limit.

Law is complex and so is legal interpretation – we should expect obviously incorrect decisions to be the exception rather than the rule. In light of this, one approach to stare decisis would be to acknowledge precedent should not be binding, but that the force of its motivating reasons such as consistency and stability of law apply especially strongly in cases where legal correctness or the proper interpretive framework is under dispute. Nonetheless, the current Supreme Court has indicated a more revisionary stance. It will become clear over the next few years how this plays out with the broader legal understanding of stare decisis in the United States.