“It is good to renew one’s wonder,” said the philosopher.

“Space travel has again made children of us all.”

– Ray Bradbury, The Martian Chronicles

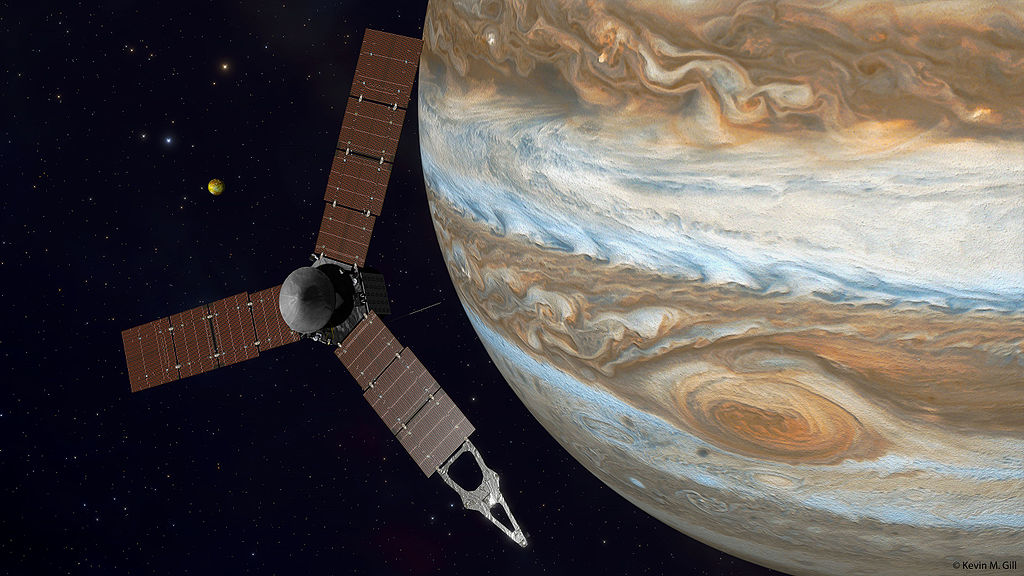

Several weeks ago, the Daily Nous published an article entitled “What Can Philosophers Contribute to Space Exploration?” The piece was triggered by a recent NASA report that highlights the “ethical, legal, and societal implications” of the Artemis program to return humans to the Moon, and – ultimately – send them to Mars. When we think of space travel, philosophers most likely aren’t the first group of individuals we bring to mind. Instead, we (rightfully) focus our attention on the scientists, engineers, and intrepid explorers who make spacefaring possible. But there is much that philosophy – and the study of ethics in particular – can contribute to these endeavors.

We stand on the cusp of a revolution in space travel. For the very first time, the heavens are no longer the exclusive preserve of government-run space programs. The privatization of space has begun. Just this week, SpaceX launched its twenty-ninth resupply mission to the International Space Station. But, while the private sector has provided a logistical lifeline to the U.S. space program – especially since the retirement of the Space Shuttle – the privatization of space has seen the cosmos quickly become yet another playground for the rich and famous. On July 11 2021, Richard Branson made history by becoming the first human to self-fund his own journey into space. He was quickly followed by Jeff Bezos a few days later. Not to be outdone, Elon Musk delivered his first private tourists into orbit just a few months later.

The costs of these trips is astronomical (pun intended). With a ticket aboard Branson’s Virgin Galactic costing a cool $250,000, one can’t help but wonder whether there might not be better ways of spending this money. Such concerns have always surrounded investment in space travel. But at least, historically, expenditure by state-run space agencies could be justified as a nationally-borne cost for nation-wide benefits. The same is not obviously true in the case of space tourism, where the benefits seem to extend only so far as the tourists themselves. Others disagree. Chris Impey – Distinguished Professor of Astronomy at the University of Arizona – argues that entrepreneurs like Branson, Bezos, and Musk “are like the high-octane fuels needed to take space travel to the next level” and that we need to “accept the risk and give the visionaries a free rein” in order to advance as a spacefaring species.

Our very own writers here at The Prindle Post have contributed much to the discussion of these potential cosmic follies. A.G. Holdier notes that a single Virgin Galactic ticket will cost the same as the annual grocery bill for 53 average U.S. families, while Carlo Davia argues that these costs can’t be justified by the purported benefits of things like innovation or ensuring that the Earth has an insurance policy. Giles Howdle, on the other hand, is more generous – taking a nuanced consequentialist approach to defend space tourism.

It’s discourse like this that truly highlights the importance of ethics for space travel. While an accountant can put a dollar value on a trip to space, and a scientist can tell you what stands to be gained from that journey, it takes an ethicist to examine whether – morally – those benefits justify that cost.

And the costs aren’t just financial. It seems that those going to space – be it for recreation or not – should be fully informed of the risks they’re assuming. There’s little doubt that many of us understand the highly dangerous nature of space travel. But it may in fact be the case that we somewhat overestimate this risk. As Impey notes, the fatality rate of spacefaring is around 2%. The fatality rate of a lifetime of driving in a car, however, is around 1.1%. What this means then, is that a single joyride to space is only about twice as risky as a lifetime of using an automobile. What does this mean for the morality – and, indeed, rationality – of taking such a journey? An ethicist can help with that.

What’s more, the ethical considerations of spacefaring even extend to those of us on the ground. As I’ve argued before, an open sky is both extrinsically and intrinsically valuable for us, yet a project link SpaceX’s Starlink threatens to take all of that way. This concern raises an even larger question: How should we treat property in space? We might think of it as a global commons – like the oceans or the Antarctic – there for the shared enjoyment of all humanity. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 seems to support this idea, claiming that no part of space can be subject to appropriation by a particular state. On the other hand, we have the approach of John Locke – who famously argued that we can appropriate common property by mixing our labor with it. What then, might we say of the Moon rocks that an astronaut judiciously shovels from the Lunar surface? Should she be able to claim ownership over these?

To complicate matters further, Locke placed a proviso on his approach to property – namely that one can only appropriate property through labor where she leaves “enough, and as good” for others. Traditionally, we might have understood this to include other members of one’s community, state, or – in the case of a global commons – the whole world. But space is so much bigger than this. In considering how we should carve up the heavens, should we also be considering the interests of beings we’ve not even met? Is the very notion of a “global commons” antiquated? Should we instead be changing our mindset to see space as a galactic commons instead?

It is precisely these kinds of questions that philosophers – and ethicists especially – are well equipped to consider. While answers might not be straightforward, nor agreement easy to find (as evidenced by the views of our very own writers), the consideration of these questions is imperative if we want to become a spacefaring race worthy of the cosmos.