“Am I good enough?” “Was someone else smarter or more talented than me?” “Am I just lazy or incompetent?” You might find these thoughts familiar. It’s an anxiety that I have felt many times in graduate school, but I don’t think it’s a unique experience. It seems to show up in other activities, including applying for college and graduate school, pursuing a career in the arts, vying for a tenure-track academic job, and trying to secure grants for scientific research. This anxiety is a moral problem, because it can perpetuate imposter syndrome – feelings of failure and a sense of worthlessness, when none of these are warranted.

The source of this anxiety is something that I would like to call “great man syndrome.” The “great man” could be a man, woman, or non-binary person. What is important is the idea that there are some extra-capable individuals who can transcend the field through sheer force of innate ability or character. Gender, race, and other social categories matter for understanding social conceptions of who has innate ability and character, which can help to explain who is more likely to suffer from this angst, but “great man syndrome” can target people from any social class.

It functions primarily by conflating innate ability or character with professional success, where that professional success is hard to come by. For those of us whose self-conceptions are built around being academics, artists, scientists, or high achievers and whose professional success is uncertain, “great man syndrome” can generate uncertainty about our basic self-worth and identity. On the other hand, those who achieve professional success can easily start to think that they are inherently superior to others.

What does “great man syndrome” look like, psychologically? First, in order to continue pursuing professional success, it’s almost necessary to be prideful and think that because I’m inherently better than others in my field in some way, I can still achieve one of the few, sought-after positions. Second, the sheer difficulty and lack of control over being professionally recognized creates constant anxiety about not producing enough or not hitting all of the nigh-unattainable markers for “great-man-ness.” Third, these myths tie our sense of well-being to our work and professional success in a way that is antithetical to proper self-respect. This results in feelings of euphoria when we are recognized professionally, but deep shame and failure when we are not. “Great man syndrome” negatively impacts our flourishing.

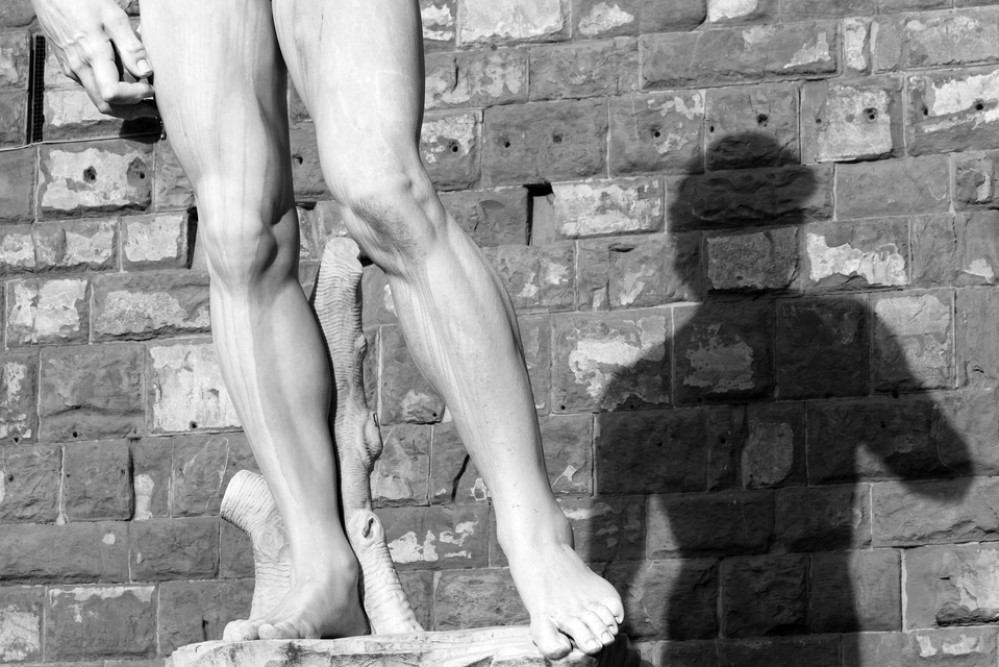

My concept of “great man syndrome” is closely related to Thomas Carlyle’s 19th century “great man theory” of history, which posits that history is largely explained by the impacts of “great men,” who, by their superior innate qualities, were able to make a great impact on the world. There are several reasons to reject Carlyle’s theory: “great men” achieve success with the help of a large host of people whose contributions often go unrecognized; focusing on innate qualities prevents us from seeing how we can grow and improve; and there are multiple examples of successful individuals who do not have the qualities we would expect of “great men.”

Even if one rejects “great man theory,” it can still be easy to fall into “great man syndrome.” Why is this the case? The answer has to do with structural issues common to the fields and practices listed above. Each example I gave above — scientific enterprises, artistic achievement, higher educational attainment, and the academic job market — has the following features. First, each of these environments are highly competitive. Second, they contain members whose identities are tied up with that field of practice. Third, if one fails to land one of the scarce, sought-after positions, there are few alternative methods of gainful employment that allow one to maintain that social identity.

The underlying problem that generates “great man syndrome” isn’t really the competition or the fact that people’s identities are tied up with these pursuits; the problem is that there are only so many positions within those fields that ensure “the social bases of self-respect.” On John Rawls’s view, “the social bases of self-respect” are aspects of institutions that support individuals by providing adequate material means for personal independence and giving them a secure sense that their aims and pursuits are valuable. To be recognized as equal citizens, people need to be structurally and socially supported in ways that promote self-respect and respect from others.

This explains why “great man syndrome” strikes at our basic self-worth — there are only so many positions that provide “the social bases of self-respect.” So, most of the people involved in those pursuits will never achieve the basic conditions of social respect so long as they stay in their field. This can be especially troubling for members of social classes that are not commonly provided “the social bases of self-respect.” Furthermore, because these areas are intrinsically valuable and tied to identity, it can be very hard to leave. Leaving can feel like failing or giving up, and those who point out the structural problems are often labeled as pessimistic or failing to see the true value of the field.

How do we solve this problem? There are a few things that we as individuals can do, and that many people within these areas are already doing. We can change how we talk about the contributions of individuals to these fields and emphasize that we are first and foremost engaged in a collective enterprise which requires that we learn from and care for each other. We can reaffirm to each other that we are worthy of respect and love as human beings regardless of how well we perform under conditions of scarcity. We can also try to reach the halls of power ourselves to change the structures that fail to provide adequate material support for those pursuing these aims.

The difficulty with these solutions is that they do not fundamentally change the underlying institutional failures to provide “the social bases of self-respect.” Some change may be effected by individuals, especially those who attain positions of power, but it will not solve the core issue. To stably ensure that all members of our society have the institutional prerequisites needed for well-being, we need to collectively reaffirm our commitment to respecting each other and providing for each other’s material needs. Only then can we ensure that “the social bases of self-respect” will be preserved over time.

Collective action of this kind itself undermines the core myth of “great man syndrome,” as it shows that change rests in the power of organization and solidarity. In the end, we must build real political and economic power to ensure that everyone has access to “the social bases of self-respect,” and that is something we can only do together.