The 2020 presidential election saw 77-year-old Joe Biden overcome 74-year-old Donald Trump, with Michael Bloomberg (78), Bernie Sanders (79) and Elizabeth Warren (71) all competitive in democratic primaries. Biden, who will be 82 when the next presidential term begins in 2025 (and 86 when it ends), has not yet decided whether he will run again, while Trump’s campaign is already in full swing. Nancy Pelosi recently lost her speakership at the age of 82, while the oldest sitting senator, Diane Feinstein, is a remarkable 89 years old and has held her position for over 30 years. Last year, septuagenarian democrats Carolyn Maloney and (76) and Jerry Nadler (75) battled it out over New York’s 12th congressional district, with 38-year-old Suraj Patel finishing a distant third.

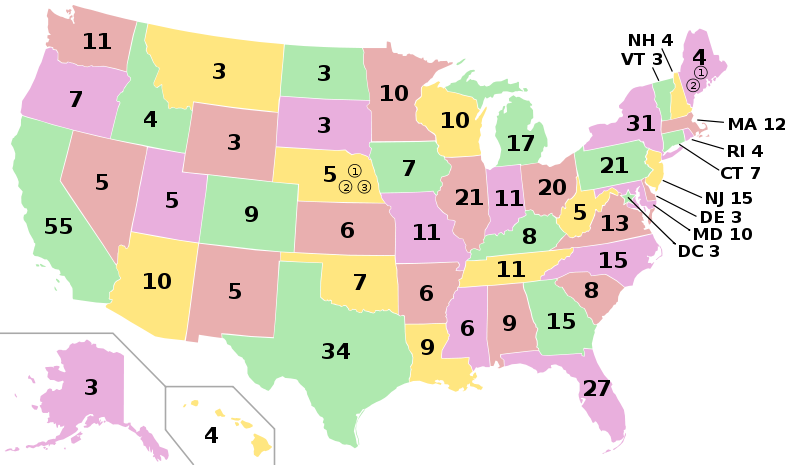

All this means that the current American government is the oldest in history. Recent suggestions to reverse this trend include term limits for senators and age limits for judges like we have in Australia, where the mandated age of retirement is 70. Business Insider has published a whole series of articles – Red, White, and Grey – on the dangers of gerontocracy, arguing that a country run by the elderly will be uniquely unrepresentative. In the U.S. as a whole, about 17% of people are over the age of 65. In congress, this rises to a whopping 50%. Elderly people tend to be whiter and wealthier than their younger counterparts.

A recent poll found that more than half of Americans support an upper age-limit for public officials. But even considering a limit of this sort raises serious ethical considerations: is it justifiable to exclude people from public office based on nothing more than their age?

One concern with gerontocracy is that elderly people will avoid long-term planning in favor of short-term gain. Why plan for 50 years in the future when you won’t be around to see the consequences? Elderly people are less concerned about climate change, for example, comfortable in the belief that it won’t “pose a serious threat” in their lifetime. But accusations of short-termism have their limits. Consider, for example, 80-year-old Mitch McConnell’s decades-long plot to capture the Supreme Court, overturn Roe v. Wade, and, in doing so, cement his legacy as a champion of the pro-life movement. Liberal opposition to his efforts has less to do with the short-term consequences of legislative flux than the long-term future of a country where women’s bodily autonomy is heavily restricted. McConnell has even suggested, without a hint of irony, that the Roe v. Wade decision is outdated. So, for better or worse, elderly leaders can retain a focus on the future.

Michael Clinton, writing for Esquire, argues that accusations of gerontocracy are simply ageism: a surprisingly socially-acceptable form of discrimination against elderly people. Ageism itself is nothing new; indeed, even Aristotle showed a prejudice against both the youthful and the aged. Philosopher Adam Woodcox presents a version of Aristotle’s approach to the elderly:

The elderly character… is pessimistic and cynical. He is distrustful since he has been let down many times; he covets wealth since he knows how difficult it is to acquire and how easy it is to lose; and he lacks confidence in the future, because things have so often gone wrong.

Age limits on public service would not only institutionalize discrimination but also risk losing the experience and “gravitas” that can only come with age. But Clinton is quite happy to endorse a minimum age on important positions – indeed, he is in favor of raising the minimum age for the presidency from 35 to 40.

Age discrimination against younger people is widespread and generally uncontroversial. Voting, drinking alcohol, driving, serving in the military, even riding on rollercoasters – all sorts of activities are locked behind age barriers. These restrictions are accepted because humans don’t fully mature – physically or mentally – until about the age of 25. But evidence also suggests that cognitive capacity declines later in life: although speech and language functions remain largely intact, executive functions – including decision-making and problem-solving abilities – decline with age.

If we have a minimum age for the presidency, why shouldn’t we have a maximum?

It is also worth considering the personal element. Loneliness and social isolation pose huge health risks for the elderly, and restricting their political involvement might have serious consequences in this regard. But this is not so much an argument against age limits on public service as a note of caution about their introduction: any initiative that restricts the ability of the elderly to run for office would have to be matched by an initiative to get them involved in other ways.

Notoriously in-touch, spacefaring, tweeting ego-machine Elon Musk thinks that the elderly are simply out of touch. He might have a point. But it remains unclear whether age limits are the best remedy. Perhaps efforts to increase active political participation among the youth might be more fruitful, as they are consistently outvoted – and out-represented – by their elders. Indeed, there are signs of change on the horizon, with a drastic increase in the youth vote at the 2020 presidential election. Unfortunately, their only options were to vote for their (great) grandparents. With Biden poised to decide on his future, the age question is certainly not going anywhere.