WARNING: The following article contains spoilers for all nine episodes of WandaVision on Disney+.

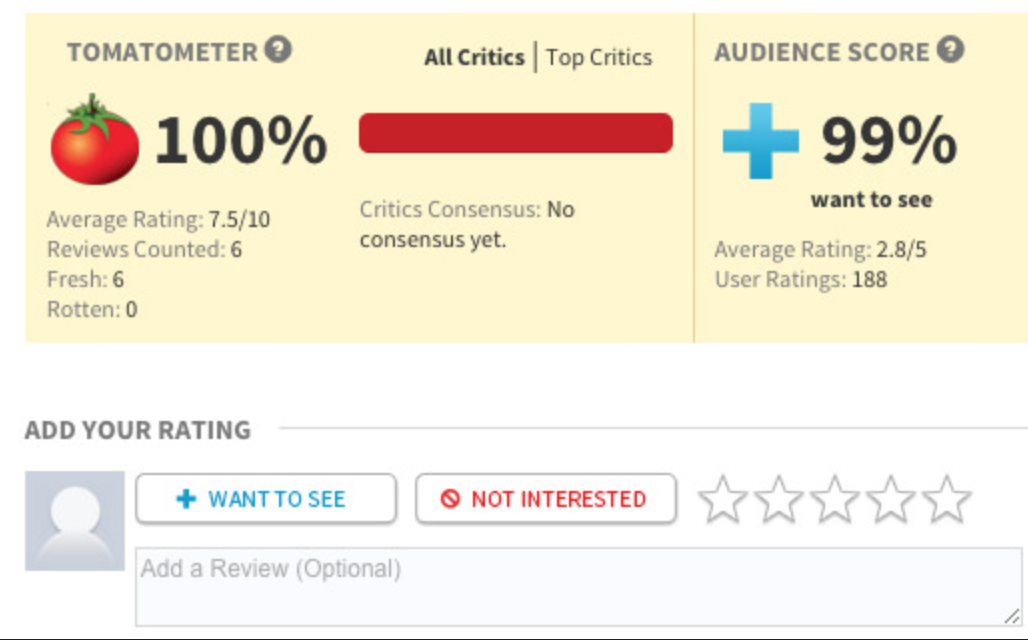

In 2019, Martin Scorsese ruffled fan-feathers when he explained why he doesn’t watch the movies in the Marvel Cinematic Universe: “I tried, you know? But that’s not cinema….It isn’t the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.” This particular sentence might sound odd to those watching the latest entry in the MCU: the 9-part limited series WandaVision on Disney+, which aims to explore experiences of intense grief and loss (even as it offers up yet another batch of costumed superheroes tossing about punches and witty one-liners).

First introduced in 2015’s Avengers: Age of Ultron, Wanda Maximoff is a super-powered magic user who (along with her brother) betrayed her villainous compatriots to assist the Avengers in saving the world. In the same film, several magical items came together inside a high-tech regeneration chamber, creating Vision, an android who could fly, fire beams of cosmic energy, and alter the density of his molecules to phase through solid matter at will. Over the course of several films, the two characters grew close and fell in love, but their relationship ended tragically when Vision sacrificed himself (at Wanda’s hand) to prevent the death of half the universe at the end of Avengers: Infinity War.

As fans of the MCU know, the story is a little more complicated than that (for example: Vision’s sacrifice turned out to be in vain, though his surviving teammates later managed to undo most of the damage in Avengers: Endgame). But the events of WandaVision begin with Wanda racked with guilt over killing Vision and mourning her many losses: her parents died when she was ten, her brother died in the climax of Age of Ultron, her powers precipitated the catastrophe that sparked the events of Captain America: Civil War, and Vision (because of some time-traveling) actually died twice at the end of Infinity War. In response to all of this, Wanda’s reality-altering powers accidentally engulf the town of Westview, New Jersey, warping it into a pastiche of various television sitcoms that Wanda enjoyed with her family as a child. Within this waking dream, Wanda is not only reunited with a reconstituted (though memory-less) Vision, but the now-happily-married couple also welcomes the birth of twin sons.

(Explaining superhero stories always sounds a bit odd, doesn’t it?)

The point is that, in various ways, WandaVision seeks to explore the painful consequences of loss and other traumas. Rather than shying away from the psychological damage done to survivors of death and terror, the show centers the experience of several characters grappling with the pain of prematurely saying goodbye to those they love. Wanda’s grief over losing Vision is mirrored in the storyline of Monica Rambeau, first introduced in 2019’s Captain Marvel and now working as an intelligence agent. Midway through the series, the audience learns that Monica was one of the people who Wanda failed to save by killing Vision in Infinity War (but who was also resurrected five years later by the Avengers in Endgame). During the interim, Monica’s mother died of cancer — something Monica learns mere minutes after returning to life and mere days before encountering Wanda in Westview.

In the penultimate episode, an antagonist leads Wanda through several of her own memories, forcing her to confront many of the most traumatic moments in her life (including the death of her parents). During these flashbacks, a scene from the early days of Wanda and Vision’s relationship took the internet by storm: while comforting Wanda after the death of her brother, Vision encourages her that even within the waves of grief buffeting her in her loss, there must still be something good: “It can’t all be sorrow, can it? I’ve always been alone, so I don’t feel the lack — it’s all I’ve ever known. I’ve never experienced loss because I’ve never had a loved one to lose. But what is grief if not love persevering?”

As you might imagine, philosophers have some other answers to this question.

Sometimes, philosophers have discussed grief as a hindrance or distraction from the “proper” objects of our attention. Consider Seneca, the Roman Stoic, who advised the daughter of a dead man to “do battle with your grief” by considering the most logical approach to find peace after her loss:

“…if the dead cannot be brought back to life, however much we may beat our breasts, if destiny remains fixed and immovable forever, not to be changed by any sorrow, however great, and death does not loose his hold of anything that he once has taken away, then let our futile grief be brought to an end.”

Often depicted (not undeservedly, at times) as unfeeling or cold, the Stoics sought to control their emotions (and all other impulses) so as to live a life governed entirely by reason. This did not mean that the Stoics considered grief (or other emotions) inherently bad, but rather that they saw how emotional dysregulation of any kind could upset the careful balance of human psychology. Certainly, at its worst, grief can threaten to overwhelm us — just as Wanda Maximoff’s story depicts.

On the other hand, philosophers have sometimes described grief or sorrow as simply constitutive of the human experience. For thinkers like Nietzsche or Schopenhauer, the painfulness of human existence meant that sorrow and loss was simply unavoidable, so the strong must confront their grief and bend it to their will. For philosophers with a more religious or existentialist bent, the reality of grief might be borne from the sinfulness of a broken Creation or from the failure of free creatures to grapple with their own mortality. Consider how the 18th century philosopher and theologian Søren Kierkegaard explained “My sorrow/grief is my baronial castle, which like an eagle’s nest is built high up on the mountain peak among the clouds. No one can take it by storm.” On these perspectives, grief is not something that can even possibly be dissolved, but rather must be harnessed and (hopefully) understood.

WandaVision’s treatment of grief is a line between these extremes: neither rejecting the emotion as inappropriate nor reveling in it as inevitable. It is a line akin to the picture found in the work of St. Augustine of Hippo, who describes in his autobiographical Confessions how the death of a loved one caused him such great distress that he nearly felt like he would die himself. Because of the love he felt for this unnamed friend (“I had felt that my soul and his soul were ‘one soul in two bodies,’” he says in IV.vi.11), Augustine was devastated by his death; regardless of death’s inevitability, “The lost life of those who dies becomes the death of those still living” (IV.ix.14).

And although Augustine (much like his Stoic forebears) infamously sought to curtail the public expressions of his grief after his conversion to Christianity (lest he suggest that the state of a departed soul was not improved by its transition to the afterlife or, even worse, pridefully demand the solace of others), Augustine never argues that grief is, in principle, sinful. In a particularly vulnerable passage, Augustine confesses how, after the death of his own mother, he found a private place and “let flow the tears which I had held back so that they ran as freely as they wished” (IX.xii.33). His love for his loved one persevered (and, in fact, drove him to an even deeper love for God).

Ultimately, WandaVision ends with Wanda realizing how her uncontrolled grief has led her to hurt the people of Westview (something a more Stoic approach to death would have avoided). Tearfully, she accepts (along with Kierkegaard) the inevitability of her pain and chooses to free the town by saying goodbye to her imaginary loved ones. But, just as Wanda’s memories and magic remain within her, so too does her love persevere; in their final moments together, the dream-Vision encourages Wanda once again: “We have said goodbye before, so it stands to reason–” at which point, Wanda sobs “…we’ll say hello again.”

Saint Augustine would indeed agree; the only real problem with Wanda’s grieving love was how she chose to express it.

In an attempt to clarify his criticism of the MCU, Martin Scorsese later published an op-ed in The New York Times where he explained how he always believed that “cinema was about revelation — aesthetic, emotional and spiritual revelation. It was about characters — the complexity of people and their contradictory and sometimes paradoxical natures, the way they can hurt one another and love one another and suddenly come face to face with themselves.” To be blunt, on such a definition, it’s hard to see how the love and pain of Wanda Maximoff fails to qualify.

And, unbeknownst to Wanda, several lingering plot threads suggest that hope does indeed remain for a genuine family reunion, but fans will have to wait for future MCU installments to see what happens next. In the meanwhile, it stands to reason that we might all benefit from reading a little more philosophy (and not just the bits about “identity metaphysics”) to help us think through our own complicated experiences of grief (and love).