Ecotourism – what the International Ecotourism Society defines as “responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment, sustains the well-being of the local people, and involves interpretation and education” – is on the rise. A recent Future Market Insights report estimates that $22.48 billion will be spent on ecotourism in 2023, rising to $90.95 billion by 2033.

While ecotourists desire to see pristine, natural spaces continue to prosper, its popularity threatens to undermine its goals. Simply by visiting these areas, ecotourists disrupt them. A sharp drop in tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that the presence of humans, as well as the noise pollution we cause, disrupts wildlife. Tourists strain local resources by consuming food and water and generating waste. They may unknowingly transport invasive species into an area, disrupting the local ecosystem. As a result, it takes a significant amount of time and money to undo the damages visitors cause. And if ecotourism increases as projected, these problems will only get worse.

Some ecotourist destinations are implementing ways to raise the funds to pay to repair these damages. The Balearic Islands charge tourists an additional tax on their accommodations. New Zealand charges many visitors a NZD $35 fee as the International Visitor Conservation and Tourism Levy, with the funds raised going towards conservation efforts. State lawmakers in Hawaii are currently considering multiple proposals to charge tourists in order to raise funds for maintaining local environments.

My present purpose is not to criticize these solutions. Indeed, there is a certain undeniable force behind the argument for them – these spaces need to be maintained, and it seems obvious that individuals benefiting from and causing additional strain on green spaces ought to be ones to pay for their maintenance. Multiple principles of environmental justice suggest as much.

Instead, I want to present a worry about the effect such policies may have on our attitudes towards these places. Arriving at this worry will require a circuitous route, however.

Several years ago, a member of my family was diagnosed with stage four liver cancer. His prognosis was immediately grim. Unfortunately, chemotherapy caused his kidneys to fail. As a result, doctors stopped his chemotherapy, and he began dialysis. I went to one of his dialysis sessions, to show emotional support during the several hours long process and to spend some time together during what seemed to be his final days. About a week later, I received a thank you card in the mail that contained money.

This gesture stirred complicated feelings in me. I was a broke graduate student – money always helped. But accepting the money made me feel dirty. It seemed to change the nature of the interaction. It took the hours spent at the dialysis center and transformed them into something that apparently warranted compensation. What was once an act that I (believe I) performed out of a combination of desire and duty now had a price tag attached to it.

In retrospect, I now think I felt moral disgust at what seemed to be the commodification of my act.

To commodify something is to turn it into, well, a commodity – the kind of thing it is appropriate to buy, sell, or exchange on the market, the kind of thing that ought to have a price tag. Philosophers are often concerned that distorts how we value things. For instance, as I have discussed elsewhere, Karl Marx argues that a world where our labor is commodified alienates us from ourselves and each other.

This may occur because commodification muddles what philosophers call instrumental and intrinsic value. Instrumental value is value in usefulness for some other goal or purpose. Perhaps the clearest example is money. We value it because money can be exchanged for goods and services, otherwise it is only good for what any other piece of paper can do. Possessing intrinsic value, on the other hand, means that something is valuable in itself or in its own right. When something is intrinsically valuable, the question of why it is valuable stops there – we do not need further explanation for why, say, the fact that it would save lives makes a particular policy valuable. These values may often be mixed. We intrinsically value people we love, but time with them is instrumentally valuable when it brings us joy.

Commodification becomes problematic when it introduces an instrumental value for what was once just intrinsically valuable. Adding this instrumental value may change our relationship to the good. Imagine, for instance, a parent who helps her child with homework every night. A rich benefactor, trying to encourage this, offers to pay her every time this happens. It is perfectly rational for the parent to accept this offer – it’s an additional reward for what she is already doing. But there seems to be something morally questionable about making and accepting such an offer. It seems to imply that putting a price tag on the child’s education is appropriate. Further, accepting this offer may cause outsiders or even the parent herself to question her true motives.

Psychologists refer to this latter phenomenon as the “Overjustification Effect” – when extrinsic rewards (an instrumental value) are attached to something participants previously found intrinsically rewarding (intrinsically valuable), they tend to be less motivated to pursue it. Whether in blood donation, children’s drawings, or solving puzzles, research has consistently found that extrinsic rewards can undermine motivation and interest. In other words, attaching an instrumental value to something may change its perceived intrinsic value.

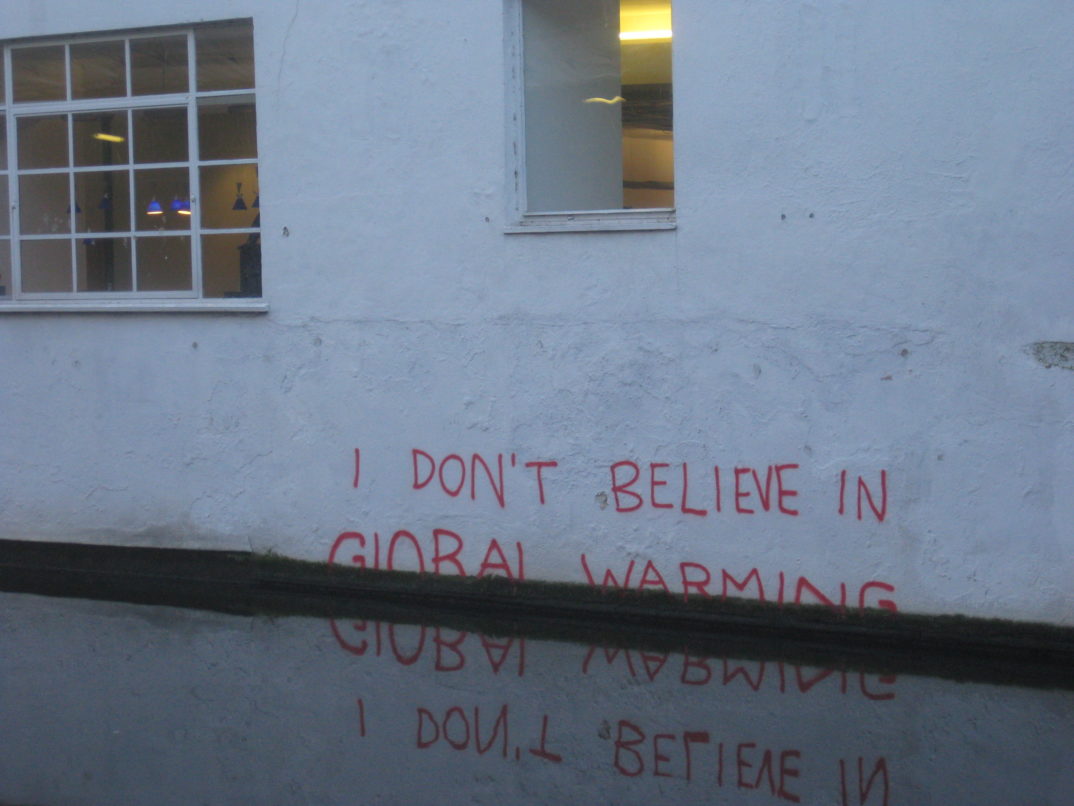

The worry that I have for taxing ecotourists is that it transforms their relationship to the natural spaces they visit.

They cease to merely be visiting and observing these places – they are paying for them. Natural space transforms to become more like the hotel they stay in and the plane they rode in on. It is, in some sense, a product they are buying. And once this occurs, our relationship to the space has changed.

Of course, the examples and data I outline above deal with rewards, in particular, giving someone money for behavior they otherwise would have performed. However, taxation proposals work in the reverse, charging tourists for behavior they would otherwise engage in. So, one might object that there is reason to doubt the process of commodification and the psychological effects I outline above occur here.

This observation is correct, but it does not undermine my point. Once financial transactions occur, they change our perception of the goods in question. When we do not pay for something, whether it is free, a gift, or a non-market good, we are more inclined to experience it for its own merits. We are more willing to take it as it comes and appreciate its own value – the best things in life are free. However, when a good is something with a price tag attached, we then adopt an attitude of comparison. We consider what else we could have done with that money and whether we made the right choice. In this way, we begin to treat the unique, intrinsic value of a particular good as appropriately comparable to other goods with a similar price point.

Again, I want to reiterate that my claims here are not a knockdown objection to tourist taxation proposals. The natural spaces that ecotourists are driven to see must be protected. But we ought to be deliberate when choosing our means of doing so and reflect carefully on how these means may change our attitudes towards these places. Perhaps taxing those who damage and benefit from these places is the best measure. Even so, we should always hesitate when it comes to policies that threaten to add an instrumental value to what we may already intrinsically value. The more willing we are to put price tags on them, the easier it becomes to treat them like any other good in the marketplace.