It is a widely accepted democratic principle that all votes should carry equal power (“One Person, One Vote”). That this is (at least generally) a good principle is less controversial than any attempt to explain why it’s a good principle. If Jeff Bezos proposed that rich people should be able to vote ten million times while everyone else should only be allowed to vote once, everyone would agree this is a bad idea. We might cite different explanations of why it’s a bad idea. We might worry about the well-being of the non-rich people, since politicians would have less reason to care about them. It might seem unfair or disrespectful to everyone else to privilege rich people in this way without a good reason. We might worry that it would make us unfree: if the government can (to some extent) boss people around, and rich people can control the government without our input, it would be like rich people were bossing us around, like they were dictators over the rest of us. We might cite more than one of these explanations, or some other one. The point is that everyone agrees that One Person, One Vote is usually a pretty good principle to follow.

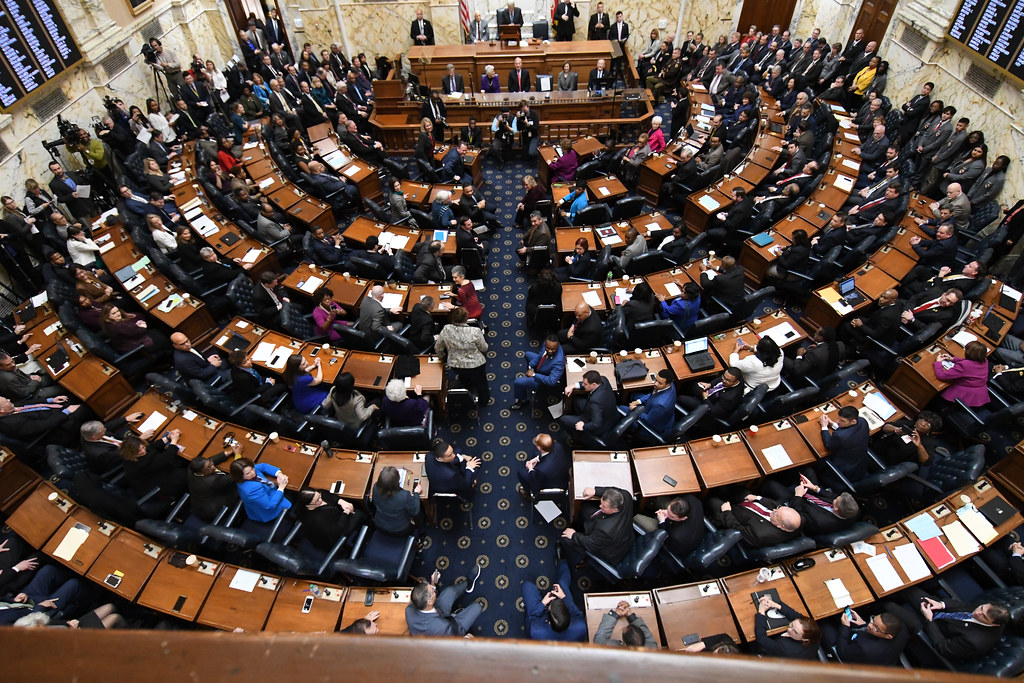

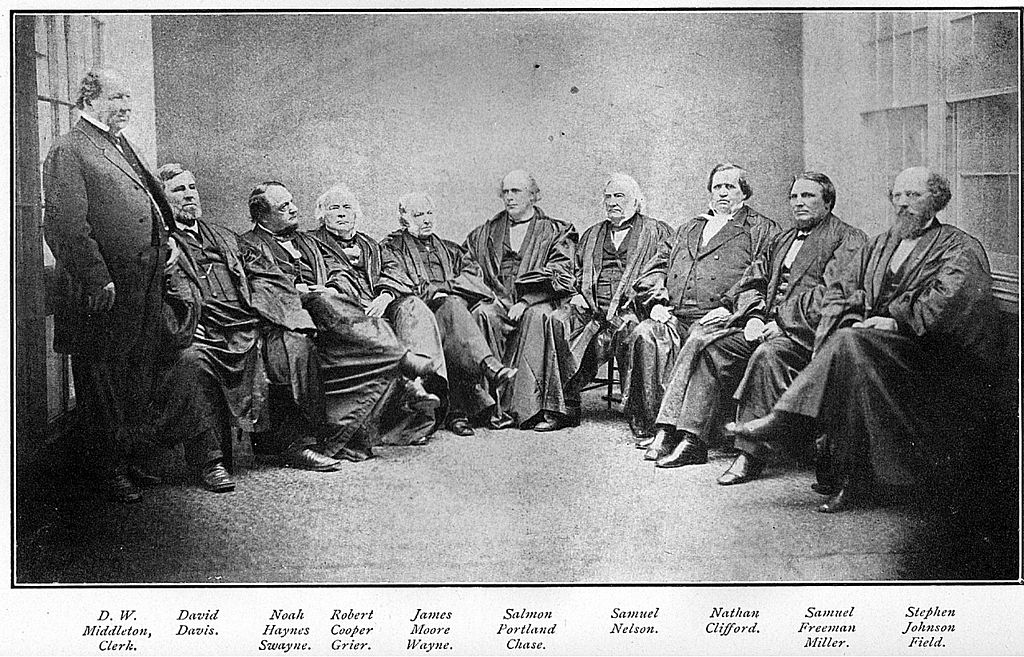

But both the U.S. Senate and the Electoral College violate One Person, One Vote. This is because they give disproportionate power to voters in low-population states. Since all states have two senators regardless of population, California and Wyoming have equal representation in the Senate even though California has about 66 times as many people. Because Senate representation affects Electoral College representation, the Electoral College is similarly biased: compared to Wyoming, California has only about 18 times the electors despite, again, having 66 times the population. Because low-population states tend to be rural, and rural voters tend to be conservative, this biases both the Senate and White House in favor of Republicans: Republicans have controlled the presidency for twelve of the past twenty years despite only winning the popular vote once in that time. Since federal judges are chosen by the president and confirmed by the Senate, the courts also favor Republicans. But keep in mind: the main point here is not about whether it’s good or bad for Republicans to be in charge. It’s instead that our departure from One Person, One Vote really is seriously affecting the government. If we gave Jeff Bezos two votes, that would be bad, but it probably wouldn’t really change anything: his extra vote probably wouldn’t make any difference. But the Senate and Electoral College do make a difference. People who want Republicans to win can still agree that they don’t want them to win like this, by violating One Person, One Vote. And people who want Democrats to win can agree that these institutions would be problematic even if they favored Democrats instead.

Some people want to change the Senate and Electoral College. For instance, the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact would functionally eliminate the Electoral College, and granting statehood to Washington, D.C. would create new Democratic-leaning Senate seats, making the body more representative. But defenders of the status quo suggest we should keep the institutions as they are to prevent American politics being dominated by the residents of populous, urban areas at the cost of rural voters. Joe Seyton at Reason writes that “By preventing the majority from getting its way all the time, the Electoral College ensures… those in high-population states with large cities aren’t the only ones who have a say.” David Harsanyi, also for Reason, says:

“because of our childish propensity to use the word ‘fair,’ I understand that the Electoral College must seem like a relic that undercuts the sacramental notion of ‘one man, one vote’… [But] the Electoral College impels presidents and their political parties to consider all Americans in rhetoric and action. By allowing two senators for both Wyoming… and California… we create more national cohesion. We protect large swaths of the nation from being bullied. We incentivize Washington, D.C.—both the president and the Senate—to craft policy that meets the needs of Colorado as well as New York.”

Tara Ross, in a video for PragerU, says that the Electoral College encourages developing platforms which appeal to the entire country: “If winning were only about getting the most votes, a candidate might concentrate all of his efforts in the biggest cities, or the biggest states. Why would that candidate care about what people in West Virginia, or Iowa, or Montana think?” And Jeff Greenfield, at Politico, writes that the Senate “protects minority interests from majority rule,” something “liberals weren’t always so fearful of.”

According to this argument, the Senate and Electoral College help address an issue related to what the political philosopher Thomas Christiano calls “the problem of persistent minorities.” If a stable bloc emerges which can win elections without needing to compete for members of a certain group, that certain group risks having its voice drowned out. This might seem unfair even when the majority makes otherwise fine decisions. If you and your two friends watch a movie every Saturday, voting on which movie to watch seems fair when a consensus can’t be reached. But if your friends like the same movies as one another, but different movies from you, and they outvote you every single time, that seems less fair. Of course, rural Republicans wouldn’t be permanently locked out of governance without the Senate or Electoral College, and so wouldn’t exactly be persistent minorities. Instead, the Republican party would change its platform to bring new voters into a coalition with these rural voters (and other Republicans) so the party could remain competitive. But the need to attract these new voters means that the rural voters’ interests would receive less priority.

Defenders of the status quo therefore endorse what I’ll call the Minoritarian Principle:

While One Person, One Vote might be good most of the time, we should sometimes depart from it by giving disproportionate power to votes from members of minority groups when this is necessary to protect their sufficiently important interests.

Majoritarianism is rule by the majority, so naturally, minoritarianism is rule by a minority. I’ve called the principle the Minoritarian Principle because it means that a minority of voters can sometimes get their way.

But we can now see the fatal flaw in the pro-status quo argument: no justification is given for applying the Minoritarian Principle only to rural voters. The interests of many different minority groups are threatened in the U.S., and prioritizing rural voters often means deprioritizing members of these other groups. For instance, since rural voters tend to be white, privileging their votes disadvantages people of color. David Leonhardt calculates that the Senate awards .35 seats per million white voters, but only .26 per million Black voters, .25 per million Asian voters, and .19 per million Hispanic voters. Meanwhile, Andrew Gelman and Piere Antoine-Kremp estimate that “whites have 16 percent more power than blacks once the Electoral College is taken into consideration, 28 percent more power than Latinos, and 57 percent more power than those who fall into the ‘other’ category.” This creates exactly the situation defenders of the status quo worry about: Republican politicians can often win elections with minimal support from racial minorities, as when Trump was elected despite getting only eight percent support among Black voters. An unusually candid statement of the racial implications of the status quo came in an interview with Maine’s former Republican governor Paul LePage. He began defending the Electoral College by saying it increases the power of small states like his, but quickly shifted to defending it on the grounds that it increases the power of white people.

Unless the interests of rural voters are at greater risk than the interests of racial minorities, favoring the former at the expense of the latter is unwarranted. But if anything, the interests of people of color are at greater risk. So the Minoritarian Principle really seems to support something like the opposite of the current system. Perhaps the votes of people of color could literally just count for more. Perhaps we could create special Senate seats to be selected by minority voters, mirroring New Zealand’s Māori electorates. Christiano considers “requiring that candidates for elective office receive quotas of votes” from different demographic groups. Many countries currently employ “reserved positions,” where offices or seats must be held by members of certain demographic groups. “Consociationalist” systems built around group power sharing of the sort found in Belgium, Switzerland, or (historically) the Netherlands might provide another source of ideas.

I’m not saying we should implement one of these alternative proposals. There are good reasons to favor One Person, One Vote, too, and maybe those should win. And implementing the alternative proposals is politically impossible anyway. This is the point instead: If we favor One Person, One Vote across the board, obviously we should oppose the Senate and Electoral College. But if, like their defenders, we instead accept the Minoritarian Principle, we should still oppose the Senate and Electoral College. These institutions have effects — like decreasing the power of people of color — which are the opposite of those a reasonable application of the Minoritarian Principle would aim for. So reforming or eliminating these institutions would also be an improvement by the lights of the Minoritarian Principle. So when defenders of the institutions invoke the Minoritarian Principle, this winds up being a red herring. Whether we accept the principle or not, we should oppose the Senate and Electoral College.