When it comes to war, does anything go? Is there no morality nor immorality in war? Is it all just prudence or imprudence, success or failure? Realists have no use for ethics; pacifists oppose all violence; just war theorists draw lines in the sand; and reductive individualists say that what is right never changes. Who should we believe?

The scholars and diplomats who call themselves “realists,” believe that morality simply does not apply to war. Realists have been, in fact, the most influential actors in American foreign affairs since World War II. The position they take, however, goes back to Thucydides, Machiavelli, and Hobbes – who all thought that morality had nothing to do with politics. Nations are always in a “state of nature” with respect to their neighbors. Even when no shots are being fired, the “war of all against all” persists – no overarching authority exists to adjudicate disputes. While morality may govern the interactions between fellow citizens during peacetime, it has no purchase when it comes to the relations between autonomous states.

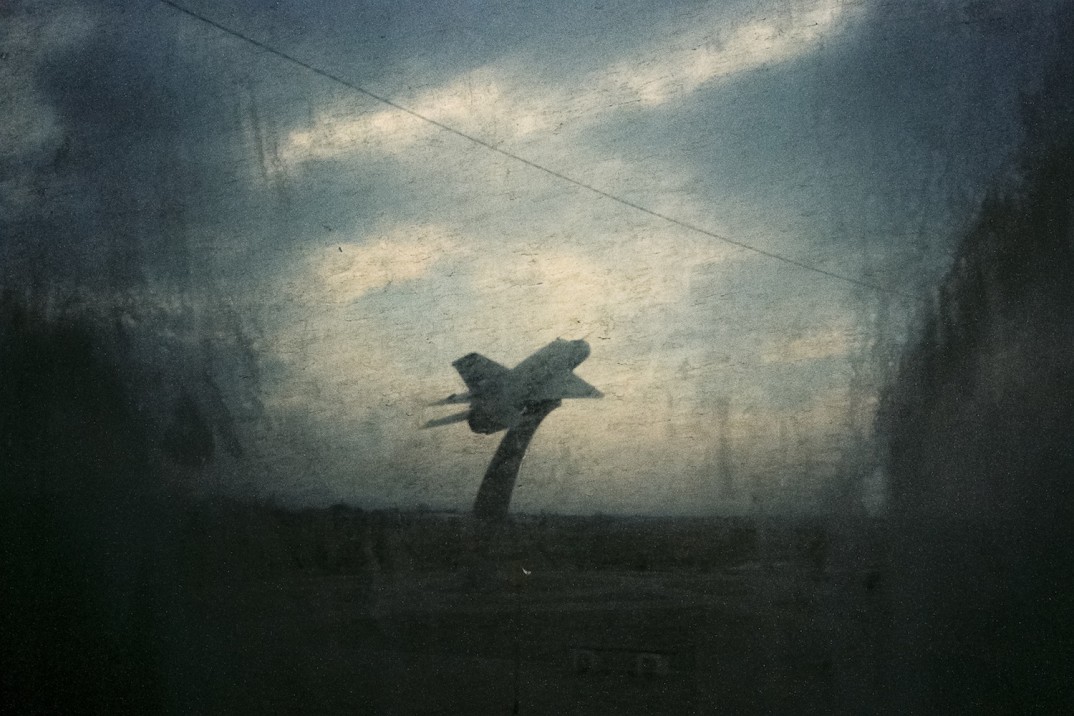

Worldwide, there are at least sixteen wars going on right now, and more than a million people have been killed. Many voices from many countries decry both how these wars started and how they are being conducted. Hopefully, most people will agree that some things – rape, torture, the murder of civilian noncombatants, the purposeful destruction of the basic infrastructure needed to sustain civilian lives – are morally wrong and should be universally condemned. If that is the case though, we must also reject the realist claim that morality has no place in war.

Perhaps war is nothing but immorality; perhaps all war is morally wrong. This is what “pacifists” believe. Even relatively restrained armed conflicts necessarily involve mass killing. That certainly looks wrong, doesn’t it? Instead of resorting to the taking up arms, the moral resolution of conflict demands and arbitration and compromise.

But what can a nation do if it is attacked? If we think that everyone has an inherent right to self-defense, shouldn’t we think countries do too? Must we stand by as innocents are victimized? Should we never intervene?

Just war theory has been trying to provide answers to these questions for at least sixteen-hundred years. It begins by distinguishing between jus in bello – justice in starting or joining a war – and jus ad bellum – justice in the conduct of a war. A just war must have a (i) just cause, be (ii) waged by a legitimate authority, as (iii) a last resort, and have a (iv) reasonable hope of success, while also being (v) a proportional response.

If it is to be a just war, the legitimate authority waging the war (i) must only undertake actions that are a military necessity, and (ii) always do so in a way that discriminates between people who are combatants and non-combatants. “The rule of proportionality,” according to West Point’s Lieber Institute on Warfare, “requires that the anticipated incidental loss of human life and damage to civilian objects should not be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage expected from the destruction of a military objective.”

These principles, and variations thereof, have been debated, extended, revised, etc. for over a thousand years. Unfortunately, they may be, as Hamlet put it, “More honored in the breach than the observance.” I will only give one example. For many older Americans, the war waged in the Pacific against the Tôjô regime after the devastating surprise attack on Pearl Harbor would be an exemplar of a just war. Yet, John Rawls, the most influential American moral philosopher of the twentieth century who fought in the Pacific himself, on the fiftieth-anniversary of the destruction Hiroshima with an atomic bomb wrote, “I believe that both the fire-bombing of Japanese cities beginning in the spring of 1945 and the later atomic bombing of Hiroshima on August 6 were very great wrongs” – and deployed just war theory to prove it.

Is there a way to look at the ethics of war without becoming a realist or a pacifist or stepping into the quick-sand of just war theory? Well, why think there is anything special, from a moral point of view, about war – other than it being especially morally abhorrent? If we have a moral code or moral rules that we follow in everyday life, why shouldn’t they apply in times of a war?

Here is the most important objection to just war theory: We would not need a separate moral theory about the ethics of war unless we meant to exempt some abhorrent conduct from ordinary moral standards.

The view that war is not exempt but bound by the same moral principles that govern the rest of human life is often called reductive individualism. It is startling, at least to me, that this is considered to be a new view. Perhaps it shows the power of nation states to shape our thinking that no one previously advocated the view that the morality of war is just ordinary, everyday morality.

I will not defend reductive individualism here. I will just make two quick points. Given the horrific nature of war, it may well be that reductive individualism is barely distinguishable from pacifism, and so, in that sense, is hardly new. On the other hand, even if we do not become reductive individualists, it may still be valuable to have this thought in the back of our mind as we follow current events. Is what I am seeing – whether or not it conforms to the laws of just war theory – moral? Not moral in any sophisticated theoretical way, just: is what I am seeing now before me right or is it wrong?