Cannons in a Quiet Park

On any other day, Belgrade’s Kalemegdan Park would have been relatively peaceful. Usually it would have been filled with people taking walks, groups of tourists and teenagers meeting their friends. Yet today a large crowd of people had gathered at the edge of the park, at an overlook above the Sava river. Just finishing a political tour of the city, my group and I joined them. In the middle of the crowd stood a cluster of soldiers- some in ornamental dress, others in camouflage – and a brass band to their left. To their right stood a group of politicians in dark suits. and in the middle of it all, half a dozen cannon barrels silhouetted against the sunset.

It was a celebration of Serbia’s independence, marking Statehood Day every February 15. At the time we didn’t know this; we had only been in Belgrade for a week, and we didn’t speak much Serbian at all. I watched through a gap in the crowd as soldiers raised the Serbian flag and a politician made a short speech. Then, the camouflaged soldiers took positions behind the cannons.

The first volley came without much warning. There isn’t a lot that can prepare you for the sheer volume of sound that heavy artillery produces, for the way that it forces the air out of your lungs and resonates in your joints. The cacophony seemed improbable, a sound so loud and so forceful that it didn’t even feel real. Yet still the cannons sounded relentlessly, over and over again.

Only after nearly a dozen rounds did the firing subside. The soldiers stepped from their positions and the crowd applauded, tentatively at first, and then louder as the band once again took up their song. My group and I returned to our tour guide, ears still ringing, as the gunpowder smoke spread through the park like an acrid morning fog. All around us, white-grey ash from the blanks descended from the treetops, settling on park benches and getting caught in onlookers’ hair – a surreal winter left in the barrage’ wake.

On the bus home, I could not get the cannons out of my head. They were an impressive sight, a marker of professionalism and strength. The spectacle also one of immense national pride, with patriotic songs and the raising of the Serbian flag bracketing the event.

But the display was also eerily reminiscent of a time when the echo of cannon fire carried an entirely different meaning. Times such as August 1991, when Serbian artillery fire entirely leveled the Croatian town of Vukovar. Or the Siege of Sarajevo, when mortars fired by Bosnian Serb paramilitaries laid waste to Bosnia-Herzegovina’s capital city for almost four years.

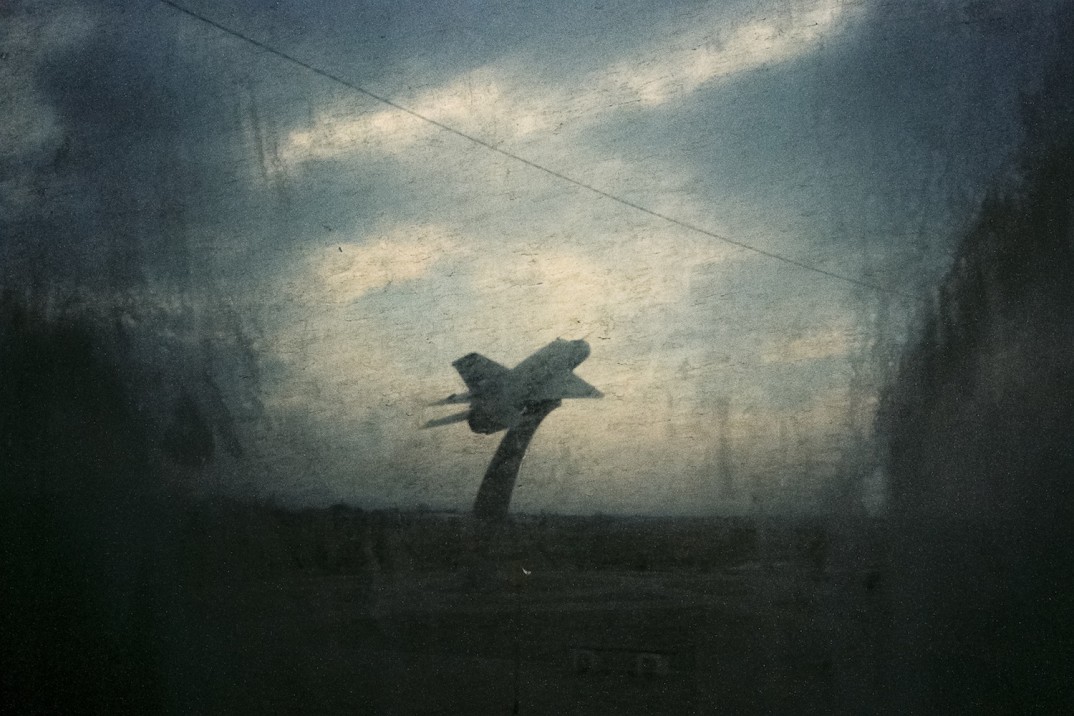

By no means is pride in the military and nation a trait unique to Serbia. In the United States in particular, the two are often considered one and the same. We fly military jets over our sports stadiums, smoke trails of red, white and blue left in the air behind them. The celebrations of our independence are meant to mimic battle, fiery explosions that seem to set wrinkles into the sky for miles around. Even our national anthem, replete with references to rockets and artillery fire, establish war as the crucible for national pride.

But how does this pride shift in light of widespread atrocity, like that largely committed by Serbian and Bosnian Serb forces during the wars of the 1990s? Just how have citizens of Serbia reconciled pride for their country and military when both have been involved in ethnic cleansing and genocide?

For some, distancing national identity from Serbia’s actions during the wars has been an important process. There are many Serbs, both from Serbia and surrounding countries, who condemn the actions of Slobodan Milosevic’s government during the 1990s. For many of these individuals, the wars of the 1990s remain a stain on Serbia’s history – a stain that has proven particularly difficult to erase.

Yet the legacy of Serbian ultranationalism can still be felt. All over the city, one can find graffiti proclaiming Kosovo as Serbian territory and depicting the “Four C’s” – a symbol of national unity heavily referenced in ultranationalist rhetoric like Slobodan Milosevic’s 1989 infamous speech at Gazimestan. At Belgrade’s notorious football derbies, nationalist hooligans celebrate Bosnian Serb war criminals with banners and chants. And the appointment of former Milosevic allies to prominent governmental positions, including that of the prime minister, has made some uneasy that potentially toxic nationalism may regain its prominence.

The roots of such nationalism are not modern phenomena. They are, in fact, critical to the reasons that the wars of the 1990s started in the first place. First harnessed by Milosevic to win power in the late 1980s, Serbian nationalism centered on narratives of the Serbs’ perceived persecution at the hands of the other Yugoslav republics. It was these sentiments that Milosevic used to justify his nationalist agenda – an agenda which led his government to create a de facto apartheid state in Kosovo and to harness the Yugoslav government to suit Serbia’s aims. These developments, which helped provoke nationalist and separatist movements in Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia, ultimately led to the republic’s disintegration.

The roots of such nationalism are heavily grounded in myths like the 1389 Battle of Kosovo, which Serbian nationalists subsequently mythologized as Serbia valiantly fighting to stop the spread of Islam into Europe. Paired with the narrative of Kosovo as the cradle of Serbian civilization, and subsequent persecution of Serbs living there, these myths formed the basis for Serbian ultranationalism. And while nowhere near the prominence they enjoyed in the early 1990s, the persistence of these narratives in public discourse has posed a number of issues for Serbia moving forward.

Such issues are also complicated by the incomplete reforms made by the Serbian government after the war. Though the 2000 ousting of Milosevic brought guarded optimism, the 2003 assassination of reform-minded Prime Minister Zoran Djindjic by former members of the Yugoslav special forces made it clear just how difficult rooting out corruption and war criminals would be. Over a decade later, human rights groups have noted that officials suspected of war crimes have not only remained in the core structure of the military, but also have been given high-level commendations. Such developments make it clear just how difficult addressing the past in Serbia has been.

–

It was April in Belgrade, and I had largely forgotten the scene I had come across in Kalemegdan in February. Walking through the park, only a few hundred meters from where the cannons stood a few months before, I stopped at a souvenir stall for a postcard. There, staring out from a pile of black T-shirts emblazoned with figures from Serbia’s past, were the faces of Ratko Mladic and Radovan Karadzic.

Before that moment, I had only seen their faces in grainy documentaries and footage from the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. But these short clips were more than enough. In them, I had seen Mladic reassuring Bosniak Muslim refugees from Srebrenica that no harm would come to them – only hours before soldiers under his command rounded thousands of men and boys onto buses and drove them to execution sites all over the countryside. I had also seen Karadzic, standing behind artillery overlooking Sarajevo, justifying his siege of the city as an attempt to drive out the Muslim descendants of occupying Turks – in itself a myth dating back to the Battle of Kosovo and Milosevic’s brand of nationalism. The siege ultimately killed over 11,000 people.

These men did not belong on a T-shirt. Both are war criminals who had ordered atrocity unparalleled, who had brought about the killing of tens of thousands in their attempts to create an ethnically pure Serb territory. Yet here they were, cast as Serbia’s heroes, staring out from a souvenir stall in the center of the city.

By no means was their presence reflective of Serbian pride as a whole. Just the same, though, it could not be ignored. For these men, a T-shirt is more than just a T-shirt. Their presentation as heroes fits into a recent trend of Serbian nationalism as defense of identity at any cost – even genocide. Facing this ultranationalism, one arguably similar to that which provoked the wars of the 90s in the first place, will continue to be a challenge for Serbs of all nationalities.

Yet there are those who have and continue to take on the task. Groups like the Women in Black and the Humanitarian Law Center have striven to hold both past and contemporary politicians accountable for Serbia’s actions during the wars. It is the work of groups like these, and the many citizens who support them, that continues the push for justice and understanding of Serbian actions in the 1990s. Similar movements can be seen all over the former Yugoslavia, as groups from all sides of the conflicts continue to strive for understanding, accountability and justice.

Between these forces of ultranationalism and truth-seeking, Serbian national pride appears to be at a crossroads. If its persistence is any indication, ultranationalism will continue to be a problem, at least for the foreseeable future. Yet the numerous voices challenging these narratives offer hope that such nationalism will eventually fade away, or at least take a less toxic form. The tensions between the two suggest that future reconciliation will not be easy. Yet, as Serbians continue to come to terms with the crimes committed in the name of their country, I certainly hope that the path towards justice is an inevitable one.