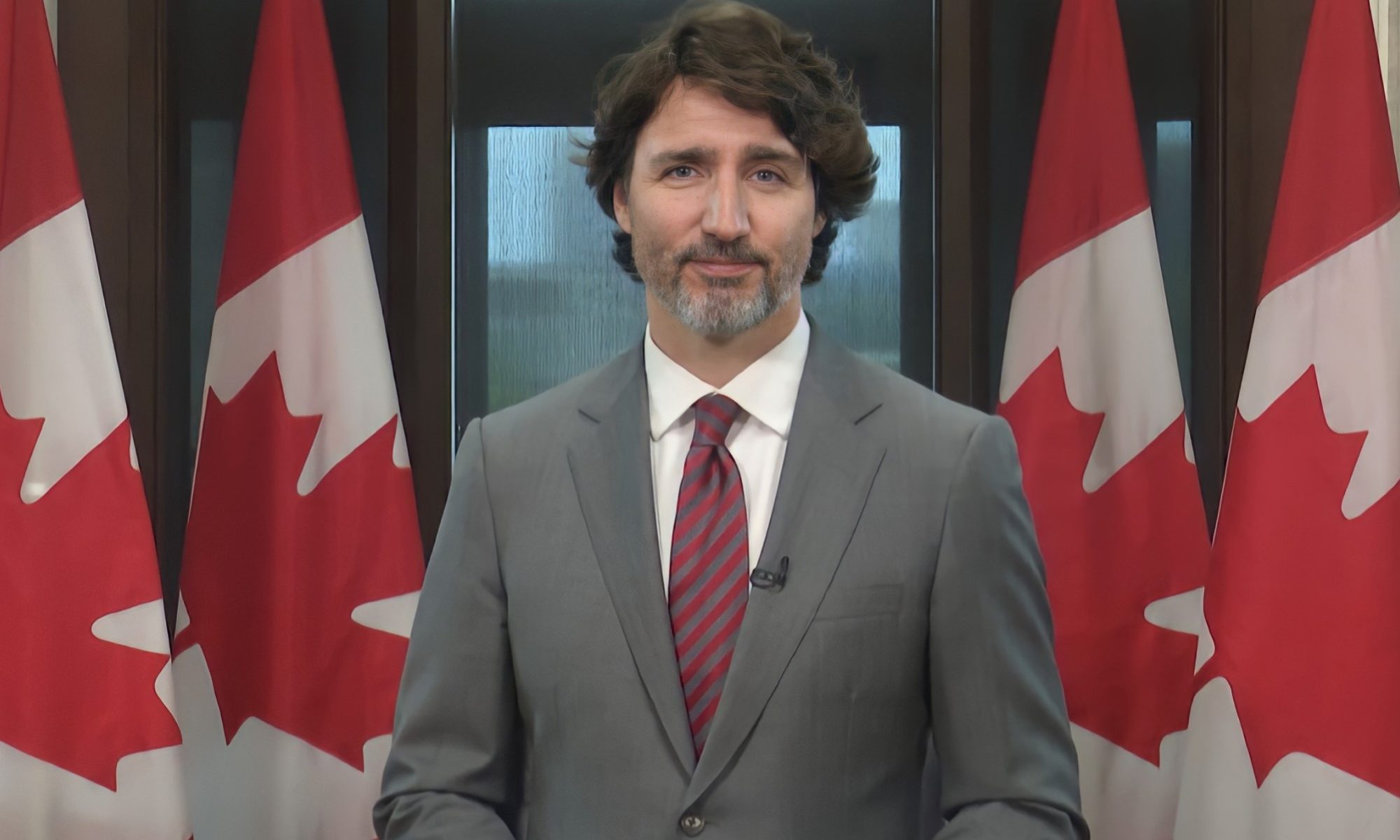

Last week Prime Minister Trudeau criticized Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki for democratic backsliding. This might seem a bit rich from someone who is mired in controversy over whether his government failed to act to stop foreign interference in elections when that interference aimed to hurt his rivals. There is no hard proof of this, but Trudeau has resisted calling a public inquiry into election interference, prompting accusations of a cover-up. Trudeau’s bizarre attempt to avoid an inquiry by appointing a “special rapporteur” recently ended, but it is far from clear whether any democratic checks to hold the Trudeau government accountable on this issue will prevail. Two years ago, I asked whether the U.S. is becoming less democratic. Given this issue in Canada, along with various other issues recently, perhaps this raises questions about the robustness of Canadian democracy and whether we are engaging in democratic backsliding of our own?

Canadian media reported that China attempted to interfere in the 2019 and 2021 Canadian elections, including threatening Canadian politicians. The Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) had advised the government that China had attempted to deploy disinformation and secure funding for preferred candidates to help the Liberal Party of Canada secure a minority government. Sources have claimed that Trudeau and his cabinet ignored these warnings. It has also been reported that China had targeted MPs like Michael Chong and that the government did not warn him. The government initially tried to claim that they weren’t briefed on this, but it was later revealed that they were aware of these efforts.

This has the potential to undermine democratic trust in Canadian elections, both because it makes it more difficult to accept the results as valid (Conservatives estimate, for example, that Chinese interference may have cost them 9 seats), but also because of the possibility that the government was either complicit or incompetent in the face of it. Thus, the public wanted a public inquiry into the issue. Yet, despite near universal calls for such an inquiry from every opposition party, only the Prime Minister can decide if a public inquiry should be called. Trudeau decided to make up an entirely new and ad hoc process to decide if an inquiry should be called by appointing a “Special Rapporteur” in the form of former Governor General David Johnston to investigate matters and on the basis of his good name alone, ask that Canadians trust Johnston to decide if an inquiry was necessary.

There were already suspicions of a conflict of interest which were only magnified when Johnston’s report announced that there would be no judicial inquiry as it would be difficult dealing with classified materials in a public inquiry. Instead, he suggested leading hearings about the experiences of diaspora communities in Canada. Canadians were not happy with this. Only 27% of Canadians polled believed that Johnston was impartial. The House of Commons passed a motion requesting his resignation and for an inquiry to be held. At first, Johnston resisted, saying he respected the right of the House to “express its opinion” but that his mandate was to the Prime Minister himself.

Does this offer evidence of democratic backsliding? Certainly such an unprecedented and improvised process raises eyebrows. The prime minister handpicked the investigator tasked with determining whether he or his government is potentially undermining Canadian elections. The investigation was conducted in private with no opportunity for cross examination of witnesses, no one testified under oath, and evidence was only provided voluntarily by the cabinet. In other words, the methods used were potentially unreliable and accountable, prompting criticism from Conservatives.

Johnston, who despite enjoying respect and admiration for his time as Governor General, has numerous ties to the Prime Minister. He was a member of the Trudeau Foundation, which had accepted donations from Chinese sources, and whose entire board recently resigned. He was also a long known acquaintance of the Prime Minister and his family, having known Trudeau as a student at McGill University and from a family friendship “rooted only in the five or six times” their families skied together years ago.

Given that Trudeau has a minority government and depends on the opposition, their governing partners in the NDP could have insisted Trudeau and Johnston, acting on their own motion. But, NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh refused to back out of his informal gentleman’s agreement to support the Liberals, citing the fact he didn’t want an election to be called while there were still doubts about election integrity. This eliminated the only realistic democratic check to keep Trudeau accountable on this issue. Until Johnston finally agreed to step down this week. Now the Liberals have even signaled that they are open to a full inquiry.

Defenders of the process have argued that Johnston is an honorable gentleman being treated unfairly – he was simply a public servant working in good faith who fell victim to partisanship. Johnston was known as a person of honor and enjoyed great respect for his nonpartisan role as Governor General. He also privately asked a retired Supreme Court Justice for his opinion on the matter and that judge said he didn’t believe there was a problem. Others have argued that anyone chosen for the job would have had the same fate; criticism was inevitable. Besides, since Johnston ultimately resigned and an inquiry looks more and more likely, perhaps the system ultimately “worked.”

On the other hand, problems with the process remain. For example, the justice who signed off on Johnston also was associated with the Trudeau Foundation at one point, and Johnston’s legal council consisted exclusively of Liberal advisors. Ultimately, the complaints highlight a trend with Trudeau’s government which has had so many conflict of interest problems. It’s gotten so bad that the Ethics Commissioner recently called for basic training for all cabinet ministers.

Does this mean that Canadian democracy is weakening? For many years, critics have expressed worry about the government depending far too much on the executive and the Prime Minister’s Office. Calls are getting louder to reign in that power. There have also been concerns regarding the government’s recent attempt to regulate speech on the internet, laws which have made Canada an outlier. Trudeau’s use of the Emergencies Act to stop a protest he helped inflame, and the use of state power to seize bank accounts serve as additional signals of the weakening of democratic guardrails. This was only further underscored by the fact that the Commissioner who investigated the use of the Emergencies Act and controversially concluded that that the threshold for its invocation had been met, had (you guessed it) a history with the Liberal Party of Canada.

The increasing polarization in the country is making it easier for politicians to try to justify some fairly sketchy policies. A significant base is all too willing to jump to their defense, purely for the purpose of partisanship. This only makes the potential for the abuse of power easier. While some might argue that Canada’s democratic system of accountability ended up working in this particular case, an inquiry is not certain and even if it comes to pass it will only be by luck and public pressure. Johnston asked Canadians to trust him and now Singh is asking Canadians to trust him to judge when Canadian elections are free from interference. But any investigation will still depend on the goodwill of Trudeau and his league of extraordinary gentlemen.