Tuesday, November 4th, was an election day in the United States. Nevertheless, if you are eligible to vote in the U.S., you likely did not do so. Perhaps you did! Voter turnout was higher than usual. Further, there may be a significant selection effect among this audience such that you, someone interested in reading public philosophy, is more likely to be electorally engaged.

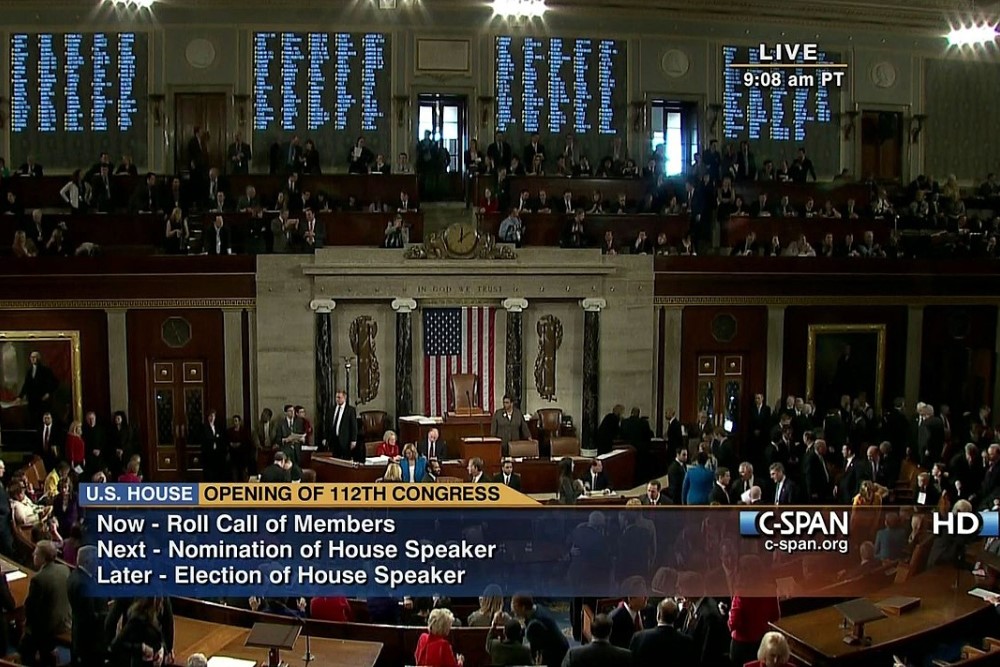

But statistically speaking, a majority of those who are eligible to vote in the U.S. don’t participate in each election, at least in recent decades. In presidential elections since 2004 between 50 and 66% of eligible voters cast a ballot, meaning that between one third and one half do not. Midterm elections typically see between 40% and 50% turnout during even-numbered years, with some years dipping into the 30’s – so most potential voters sit these out.

But turnout for local elections, especially those which occur in odd numbered “off-years,” is the most troublingly low. Data are hard to gather, given that these elections are (usually) not for federal offices and thus take place at the town, county, or state level. Regardless, the available data suggest that turnout for most local elections ranges from low to shockingly low; mayoral elections usually see about 20% turnout even in major cities, while other offices such as school board, town supervisors, or city council members may see turnout drop into single digits.

There are several reasons we might be troubled by this. I want to articulate at least three philosophical reasons for concern. First, there are epistemic issues. Going back to (at least) Aristotle, theorists have argued that what makes democracies special is that, by having many participate in the political process, we can access knowledge that may be inaccessible if only a minority participate. The idea here is that, through accessing the aggregate of everyone’s views, we are more likely to come upon the right view.

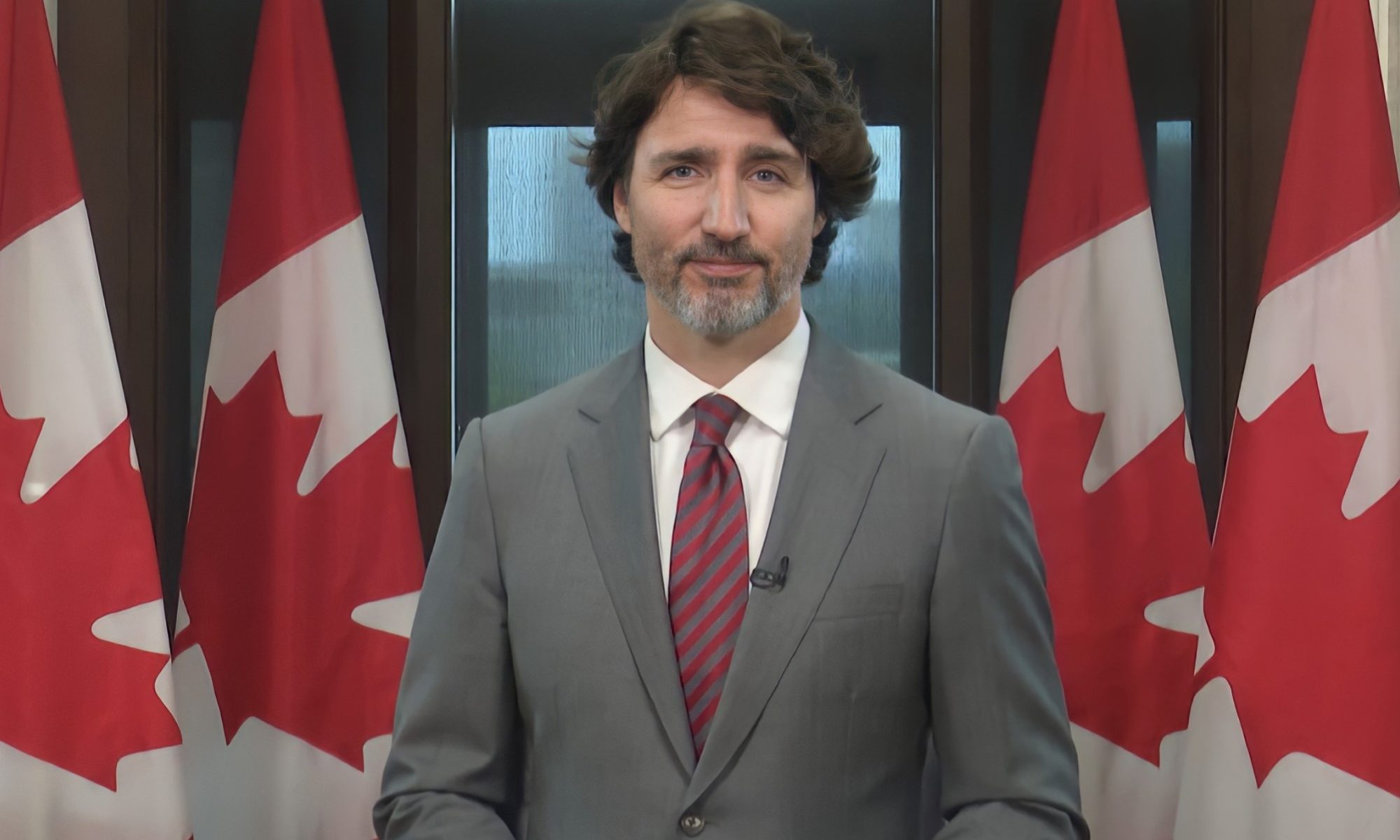

Exceptionally low turnout elections run counter to this proposed advantage of democracy. Instead, they appear to more closely resemble an aristocracy, rule by a small number of elites – only a select few participate in determining the outcome of these elections. Thus, if democracy is in part justified by its unique advantage in reaching the right answers, then we have reason to doubt the merits of elections where only a small minority participate as their verdicts are not a collective aggregate.

Second, one might worry about the legitimacy of any institutions whose officers are determined by only a small number of voters. Many contend that governments are only morally justified via the consent of the governed. It is this idea that gives democratic institutions their legitimacy; voting is the procedure by which we indicate our preferences and express consent for the outcome that emerges. However, when very few participate in the elections, we have serious reason to doubt the moral legitimacy of those selected. Only a small minority express a preference for them and thus the rest are giving, at best, tacit consent to grant power to those officials.

However, I think that closer examination of this issue – the role of elections in shaping governmental legitimacy – will reveal a larger issue to which low turnout elections give rise. It seems to me that low voter turnout will help to enable electoral nihilism. By this I mean the view that there is no good reason to participate in elections. The fewer people that participate in elections, the more likely it is that potential voters will become electorally nihilistic.

This may seem counter intuitive. I am claiming that not participating in elections, particularly local elections, may lead someone to believe that engaging in the electoral process is pointless. One would think that the order of operations would go in reverse – the view that it is pointless comes first, which then deflates the desire to participate.

But think carefully about the elections in which most voters do not participate, local elections. These are the elections which a) will have the most immediate, direct effect on their lives and b) are those where their vote will have the most power.

Suppose, for instance, that my town has a referendum on funding a new park. The referendum passing could produce a material change in my life and do so relatively quickly – the park would provide new opportunities for recreation, a new venue for events, etc. If I voted in favor of the referendum and it passed, I may see the results of my action and its impact on my life in short order.

Compare this to political action at the federal level. Former President Barack Obama, before leaving office, compared federal policy to steering a very large ship; it takes a long time to turn the boat in a new direction, and slight, even imperceptible, changes at one moment can result in arriving at a very different destination given enough time. Few of us feel the effects of federal level elections soon after they occur. Of course, there will be exceptions – candidates may campaign on, and follow through with, policies that involve aggressively targeting specific groups, threaten to upend the economic or social order, and lead to war. But our vote at the federal level generally takes more time to trickle down to our individual lives.

Additionally, just mathematically speaking, our vote at the local level carries more weight. Given that there are fewer voters in a local election, each single vote matters much more. There is a real sense in which votes for federal offices do not matter. In the 2024 elections, out of 468 elections for seats in the House and Senate, only 43 had a margin of victory under 5%. However, the closest race in the Senate was won by 15,000 votes, while the most competitive House race had a margin of 187 votes. For presidential elections, the only voters who appear to shape the outcome of the elections are tens of thousands of voters across the battleground states. There is a real sense in which one simply casts their ballot into the ether in these elections. One can hardly be blamed for thinking that there is no point in participating in these circumstances.

Local elections, however, are quite different. The 2025 mayoral election for Johnson City, New York, a town where I lived during graduate school, was apparently decided by just 9 votes. No single person’s vote changed the outcome of this election, but one person’s actions may have or could have changed the outcome – one day of canvassing, one night of phone banking, one trip to take voters in need of a ride to the polls, or a few conversations with friends, could have added or flipped enough votes to change the victor. One’s personal vote, and their election related actions, are much more impactful on the local level. Thus, when one is regularly participating in local elections, it is far more difficult to collapse into electoral nihilism. The results of one’s efforts are readily apparent.

Of course, there are significant challenges to participating in local elections. As our sources of news have become more nationalized, 40% of local newspapers have gone out of business, resulting in 50 million Americans living in “news deserts” where there is extremely limited (or no) news coverage of local events and, by extension, elections. This is especially troubling given that the power to vote comes with responsibilities, specifically the responsibility to be informed. Voters may need to do significant personal research to find out who and what precisely is on their ballot, then dedicate efforts towards gathering information about the specific platforms for each candidate.

So why put in this effort to avoid electoral nihilism? At least initially, I think there are two primary reasons. First, Americans’ confidence in their democracy is at an all-time low. Of course, addressing this will require systemic reforms. But ensuring that one feels that voting matters seems to be a necessary first step to any changes. Second, reducing electoral nihilism may lead to more responsible voter behavior. When one feels that one’s vote is meaningless, it becomes easier to vote for fictional characters, or to treat your vote as a joke – when nothing matters, then anything is permitted. In a democratic society, we ought to be prepared to, even if only hypothetically, provide a good justification for how we fill out our ballot. It seems that a necessary first step along the way to developing this justification, is to think that one is doing something that matters with one’s vote. Being an engaged, informed and responsible voter is hard work, and hard work may not be worth doing if one feels that it does not matter.