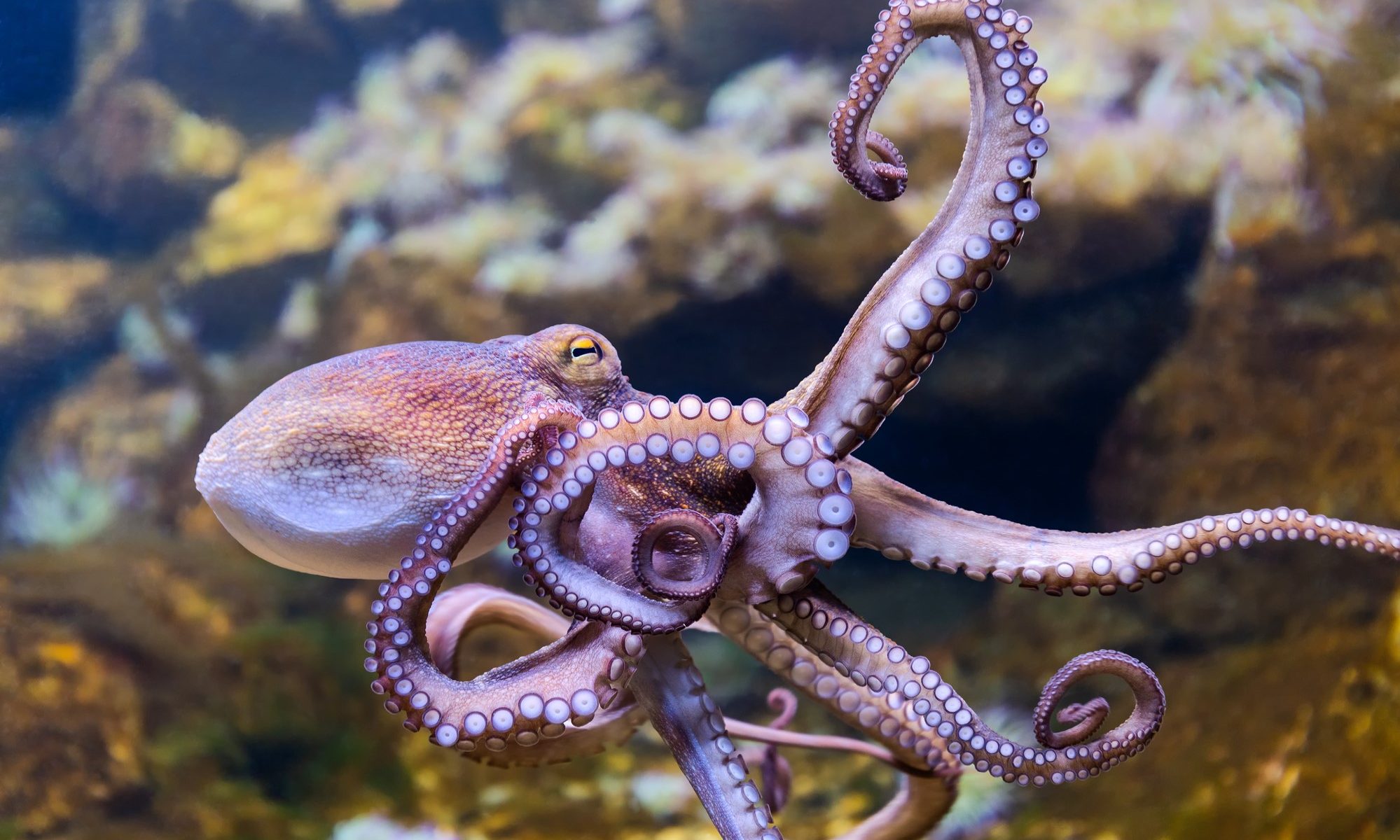

In March of 2023, news agencies reported that Nueva Pescanova, a Spanish multinational corporation, is planning to intensively farm octopuses in the Canary Islands. The proposal for the farm describes farming a million octopuses a year for slaughter and sale as food. Octopuses are extremely intelligent. They are capable of using tools and engage in high-level problem solving. The documentary My Octopus Teacher, which highlighted the capabilities of these animals won the Academy Award for best documentary in 2021. The best-selling book Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Origins of Deep Consciousness by Peter Godfrey-Smith pursued critical questions about what it is for a creature to be conscious and how that consciousness manifests itself. These questions have moral implications that we should not take lightly.

In Meditations on First Philosophy, Descartes famously argued that he could know beyond all doubt that he existed as a thinking thing. Though each of us may be justified in belief in our own existence, we can be less certain in the case of the consciousness of other individuals, including other humans. The best we can do is note similarities in structure and behavior and conclude that similar creatures are likely also conscious, especially if they are capable of telling us that they are. In Discourse on the Method Descartes argued that the ability to use language or other signs to express thoughts was the evidence available to us that another being has a soul. He argued that the fact that non-human animals only express passions through behavior and not thought in a language demonstrates that,

They have no reason at all, and that it is nature which acts in them according to the disposition of their organs, just as a clock, which is only composed of wheels and weights is able to tell the hours and measure the time more correctly than we can do with all of our wisdom.

Descartes is just one historical figure in a long line of thinkers who define what we might now call consciousness in very anthropocentric ways — human beings represent the gold standard, the rational animal. In Other Minds, Godfrey-Smith argues that consciousness is so evolutionarily advantageous that it might have evolved in response to different environmental pressures in different circumstances, and this may be just how it happened in the case of the octopus. Octopuses have consciousness distributed through “mini-brains” throughout their body. This raises many significant philosophical questions and strongly suggests that if we use human consciousness as a standard for what the phenomenon is or could be, we’d likely end up with an impoverished take on the concept. Questions of consciousness don’t just impact interactions with other humans or non-human animals. They are also relevant to our future interactions with advanced technology. It’s important to do our best to get it right.

If octopuses exhibit behavior that indicates significant intelligence and their biological structure suggests a kind of consciousness that we know very little about, the situation demands erring on the side of caution. This is an argument not only against intensively farming these creatures but also against killing them at all for food or for any other human purpose. If it’s wrong to kill intelligent creatures, it seems sociopathic to farm millions of them for food every year.

Nueva Pescanova claims that the deaths of these octopuses would be painless. There are several questions that need to be asked and answered in response to this claim. First, is it true? The company plans to kill the animals by placing them in water kept at -3C. They allege that this is a humane and painless form of death. This is a controversial claim. Some experts insist that this form of death is particularly slow and painful and for this reason some supermarkets have already stopped selling seafood killed in ice baths.

Second, if the death is painless, does that entail that the killing is morally acceptable? Some philosophers have suggested that it does, at least if the creature in question has no sense of time or capacity to fear their own death (see, for example, Peter Singer’s arguments in Practical Ethics). There are at least two main responses to this line of thought. First, the problem of other minds reemerges with a vengeance here. What does it mean to have a sense of time or to fear one’s death? Can these capacities manifest themselves in different minds in different ways? Do they require articulation of thoughts in a language or is the presence of certain dispositions to behave sufficient? Second, killings are not justified just because they’re painless. If Bob sneaks up behind Joe and kills him painlessly, he nevertheless, all things being equal, does something seriously morally wrong. Among other things, he deprives Joe of a future of positive experiences. As philosopher Thomas Nagel argues in his famous paper Death, the badness of death consists in the deprivation of the goods of life. This is a deprivation that both humans and non-humans are capable of undergoing. If death is bad for humans for other additional reasons related to their cognitive abilities, those might be additional reasons that death is particularly bad for an intelligent creature like an octopus as well.

The prospect of intensively farming octopuses is particularly troubling because of their intelligence. That said, the practice of intensively farming sentient creatures at all raises very serious moral concerns. Intensive farming involves mistreatment of animals. It causes them pain and it violates their autonomy. It recklessly disregards the care obligations we have to vulnerable populations. It weakens our moral characters by encouraging us to think of other sentient creatures as things rather than as beings with minds and experiences of their own. The case of the octopus motivates thought about the problem of other minds and the many forms consciousness could potentially take. If we ought to err on the side of caution when it comes to minds that are different, there is an even stronger case for doing so when minds are the same. There are many historical examples of the use of uncertainty about other minds to discriminate and oppress people on the basis of race, gender, age, ethnicity, and so on. People have too often concluded that if another mind is unknowable, it must be inferior, and this has been the cause of the worst atrocities perpetrated on humans by humans. We should stop engaging in the very same behavior when it comes to non-human animals. Intelligent creatures should not be intensively farmed nor should any sentient animal at all.