In honor of tonight’s “Motherhood in Prison” panel discussion at Prindle, as well as my own mother’s birthday later this week, it seems fitting to discuss the one code of ethics that most individuals seem to have in common: The “Mom Test.” Often manifested in the question “Would your mother approve?”, this test reveals a hidden aspect of our individual ethical codes.

Is Sharyl Attkisson a victim of Obama administration?

Former CBS correspondent Sharyl Attkisson is either a paranoid kook or victim of one of the most heinous government abuses of a reporter in American history. Either way, the rest of the journalism community should be jumping into action to determine the truth. Sadly, it is not.

Atkisson claims in her new book that the federal government hacked into her computer to track and disrupt her investigative reporting of the Benghazi attacks and the Fast and Furious gun transactions. Both of these matters linger with unanswered questions. Attkisson has been one of the few reporters digging into these important stories, while many news organizations find no room for such news.

This is one of those awkward situations when a journalist becomes a focus of the news, instead of just reporting it. Attkisson has a solid track record as an enterprising and capable reporter, having worked at CNN in the early 1990s and for 21 years at CBS. She left CBS this year, reportedly over disagreements with network brass about the aggressiveness with which she pursued these controversial stories.

America needs to have Attkisson’s allegations carefully scrutinized. Citizens need to know if our government has made an assault on the free press. Inasmuch as the press is a surrogate for the public, this kind of media abuse would, in essence, be an attack on the American people.

Attkisson’s charges, while still needing full and independent verification, are plausible, given what else is known about how the Obama administration has targeted journalists. To assess this plausibility, check with New York Times reporter James Risen, who still faces jail time for failing to reveal his news sources to the Justice Department. Check with Fox News Channel’s chief Washington correspondent James Rosen, who had his electronic communications and those of his parents monitored by the government. Or check with Associated Press reporters who had their phones tapped, resulting in the drying up of untold news sources. And who knows what other media outlets might now be subjected to government snooping? That’s the scary part.

Press attention to the Attkisson situation has been sparse to the point of irresponsibility. Readers and viewers of many traditional media outlets would never know of Attkisson’s allegations. Perhaps the editors and producers of those outlets just don’t believe Attkisson. Or maybe they fear reprisals from an Obama administration that makes little secret of its disdain for the press. If journalists’ failure to fully look into the abuse of Attkisson is based on fear, then shame on them.

Journalism industry leaders, after years of taking it on the chin from the government, are finally beginning to speak up. The New York Times Editorial Board recently blasted Attorney General Eric Holder, saying he “bears responsibility for undermining robust journalism.” USA Today’s D.C. Bureau Chief Susan Page said recently that the current White House was “more dangerous” to the media than any prior administration. Society of Professional Journalists President David Cuillier sent a letter to the White House this summer complaining of a lack of government transparency. When the White House sent a weak response, Cuillier called it “typical spin and response through non-response,” adding, “We are tired of words and evasion.”

The resources of the free and powerful journalism industry must be focused now on digging into Attkisson’s charges. First Amendment protections mean nothing if the free press doesn’t actively pursue the prospect of the government hacking the computer of a prominent reporter. If it did happen, the citizens need to know why, by whom and at whose direction. This story should lead every network newscast and front every newspaper until it is determined either that Atkisson’s charges are accurate or that she is a fraud. If it is the latter, then Attkisson’s journalism career will be declared over. If it is the former, then the media must commit to seeing the responsible government officials punished.

‘Like a Girl:’ A cultural context

We have all heard it before: the kid out on the baseball field shouts, “you hit like a girl.” Adults do it too. In fact, just last fall my sister’s soccer coach yelled to his son, “you’re running like a girl,” upsetting many parents in the crowd. To many, to be “like a girl” means to be, somehow, less.

In one of their most recent ad campaigns Always, a feminine products company, is raising awareness about the connotations attached with the phrase, “like a girl.” We often subconsciously assume that to be “like a girl” is to be weak, victimized and, ultimately, incapable. These systems of belief are imbedded in a culture where young girls are taught to believe these things about themselves. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, often reinforced by peers, parents and mentors.

“My Beautiful Failure” and Competition in Higher Education

Continued education, especially college, has long been seen as a positive and transformative experience, changing those who enroll and readying them for the world after graduation. But what happens when unhealthy competition enters the mix?

Columnist and mother Lucy Clark knows all too well. In her piece, strikingly titled, “My daughter, my beautiful failure,” Clark details just how damaging a competitive and results-driven atmosphere was for her daughter, who struggled to graduate high school. Contrary to popular narratives, though, Clark argues that this is hardly a personal failure, but in part the result of an educational system focused on winners and losers, where personal achievement and class rank dictate the behavior of those involved.

Continue reading ““My Beautiful Failure” and Competition in Higher Education”

WARNING: Technological Invasion

Apple’s new iWatch, expected to hit markets early in 2015, advances time keeping to a whole new level. Not only does the iWatch keep accurate global time, automatically adjusting to different time zones via satellite, it also tracks daily fitness and provides a way to respond to messages, calls and notifications more easily than we already can. Offering features similar to a smartphone, the iWatch stands to revolutionize the ability to connect with others on a timely basis. Reality is, the iWatch may even take the place of phones when everything you need is literally “strapped” to your wrist. Although this gadget will surely be a hot commodity when it hits markets, from an ethical standpoint, one may question the role technology ought to play in human life? Will the iWatch consequently distract people from partaking in meaningful conversations and being present in the moment?

Read More…

In Professor Nichols-Pethick’s Media, Culture, and Society class, these questions where further explored. As technology continues to evolve and advance the way we live, one cannot deny the positives that have surfaced. In fast-paced daily lives, people can easily stay in touch and communicate with each other on the go. The iWatch would surely improve this efficient communication. When you find yourself with a strong urge to send a text or check an email, you will not have to rudely take out your phone anymore. You can appear focused and tuned in while doing your own thing via the iWatch.

However, there are undoubtedly drawbacks. While on the one hand, the iWatch is convenient and trendy, it is also a troubling innovation. The iWatch fastened tight to your wrist, quite literally, becomes a part of you and makes it increasingly hard to be “off the gird.” Wearing the iWatch will serve as a constant reminder that you are always connected. It might become even harder to escape than a phone or computer because it is literally fastened to your person. Alone time could become a thing of the past. Even more unsettling, a special new feature allows the iWatch to offer “human like taps” as an alternative way to connect with others. Technology seems to be creating ways to embody human interactions.

Although we cannot prevent new technology from being created, we can become more aware of what we might be losing as a result to these technological advances. Efficiency is tempting in our fast paced lives, but keeping tangible relationships with those we care about is more important. Humans should strive to step out from behind the screens of phones, computers and soon to be iWatches, and experience life first hand through meaningful relationships and face-to-face conversations.

Zero Tolerance, Zero Learning

In honor of this week’s Kids for Ca$h documentary screening, it might be good to revisit a school policy with the potential to land misbehaving children in jail: zero tolerance policies.

What Do Politicians Actually Need To Know?

“I’m not a scientist” is the most common response made by Republican Party members when discussing climate change. New York Times “Political Memo” by Carol Davenport humorously discusses this rather banal avoidance of the issue. But what comes across at first as a simple political mechanism actually raises an interesting question: should politicians — or law-makers, or anyone who can influence public policy, for that matter — have an ethical responsibility to be educated in the subjects they make policies about? Continue reading “What Do Politicians Actually Need To Know?”

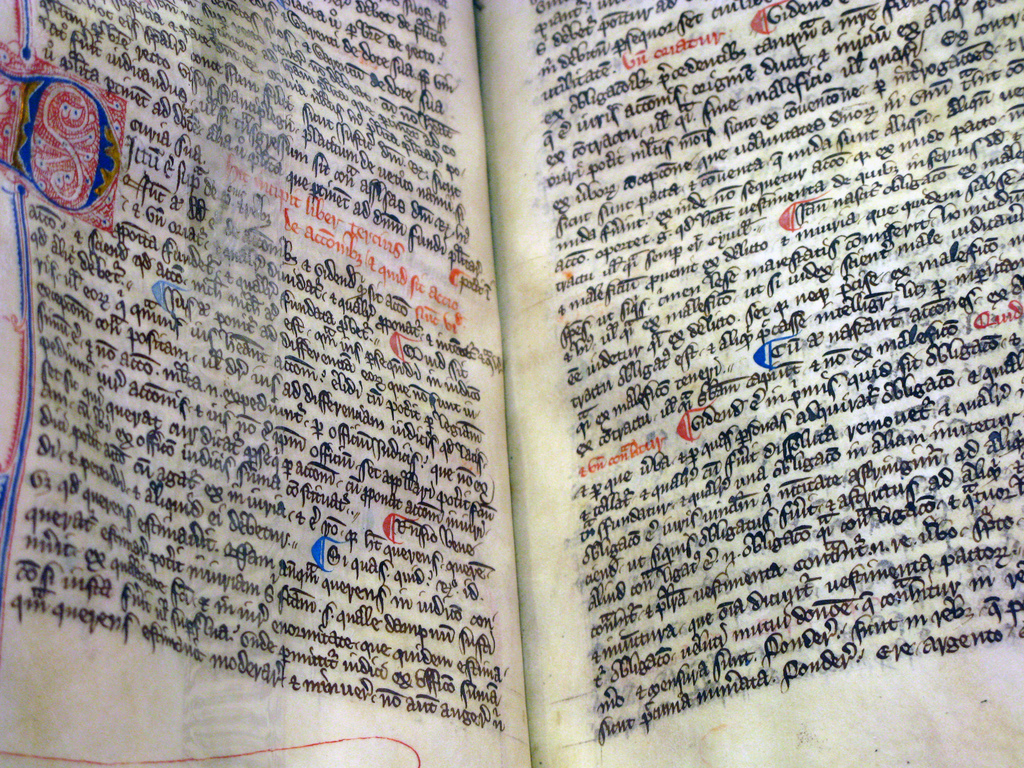

Destroying Medieval Books – And Why That’s Useful

By Erik Kwakkel

This post was originally posted at Medieval Books, and is posted here with Dr. Kwakkel’s permission.

Old furniture, broken cups, worn-out shoes and stinky mattresses: we don’t think twice about throwing things out that we don’t need anymore. And books? Here things are a bit different. Apart from the fact that you may find it morally abject to throw out a book, that noble carrier of ideas, the object retains its economic value much longer than many other man-made things. Old and worn books will usually have a second – third, fourth or fifth – life in them, for example on the shelves of the secondhand bookstore. Indeed, old age may even increase their value dramatically, as visitors of book auctions will know.

The final curtain call of any book, including medieval ones, is when its content is no longer deemed correct, valid, or useful. Between the end of the Middle Ages and the nineteenth century thousands and thousands of medieval manuscripts were torn apart, ripped to pieces, boiled, burned, and stripped for parts. While these atrocities were undertaken to various ends, the ultimate explanation for this literary genocide is the same: the old-fashioned parchment book had run its course. It was forced to bow and leave the stage, where the printed book was now stealing the show. This post sheds light on a dark chapter of wilful destruction – which came with surprising benefits for the culprits.

Culprit 1: The Bookbinder

If you have followed my blogs – both here and on Tumblr – you known I have a soft spot for so-called manuscript “fragments”. Ranging from small snippets no larger than your pinky to full leaves, they were the product of the knives of bookbinders. When Gutenberg invented moving type, handwritten books became old-fashioned overnight. All over Europe they subsequently became the victims of recycling at the hands of binders, who cut them into pieces and pasted them inside bookbindings, where they often still remain. And so we encounter a little strip from a medieval Dutch Bible glued to the inside of a sixteenth-century binding (Fig. 1); and snippets from a medieval Hebrew text peeping out of a damaged binding (pic at the top). These examples show how medieval books were mutilated and stripped for parts, like cars at a scrap yard. Thousands of them disappeared this way – though fortunately not without a trace.

Culprit 2: The Tailor

The strength and durability of parchment made medieval pages ideal for supporting bookbindings. Tailors loved to recycle the material for the same reason. The pages in Fig. 2 form the lining of a bishop’s mitre, to which a layer of cloth was subsequently pasted. The practice is observed in other mitres as well (two examples are mentioned in the comments at the bottom of thisblog). What’s really remarkable about the lining seen above is not so much that the poor bishop had a bunch of hidden medieval pages on his head, but that they were cut from a Norwegian translation of Old French love poetry (so-called lais). Lovers were chasing each other through dark corridors, maidens were frolicking in the fields, knights were butchering each other over nothing. All the while the oblivious bishop was performing the rites of the Holy Mass.

There are other examples where tailors (I’m putting mitre makers under this label for convenience) used leaves from medieval manuscripts to “stiffen” the cloth. Dr. Lähnemann, chair of German Studies at Newcastle University, has identified several such cloth items with hidden content in her work. An unusual case is seen in Fig. 3: a dress made in the late fifteenth century by Cistercian nuns in Wienhausen, Germany. It was not meant to be worn by people, however, but to be draped around a statue in the convent. It’s not unlike doll’s clothes you pick up in the toy store today, except that the remains of a Latin text are hidden inside.

Culprit 3: The Scribe

And then there were the scribes. Surrounded by used books and with a pen knife in their hand, makers of medieval books were bound to do some damage. There are several ways in which old pages could be put to good use in the monastic scriptorium or library. You can make bookmarks out of them, as I have shown in a recent post (here). A more hidden way of recycling concerns the so-calledpalimpsest, where the words were scraped off a page after which a new text was copied down on it. In the early Middle Ages entire books were palimpsested. There was a definite upside to this practice from the scribe’s point of view. It gave him, without effort, a pile of parchment to fill with something new: it allowed him to cut corners without having to cut corners, so to speak (Fig. 4).

There was a downside as well. As seen in Fig. 4, the scraped away lower text never fully disappeared from sight: it tended to pop up unexpectedly throughout the new book. While the text at the forefront (the upper text) of this spectacular manuscript dates from the eight century, what’s hidden underneath it is much older. To produce this manuscript a fifth-century copy of Paul to the Romans was palimpsested, as well as parts of a sixth-century Gospel Book in Greek uncial letters (the blue text that is shining through).

The last words: the joys of destruction

While it is a thrill to look for bits and pieces of medieval text inside a bookbinding or below the surface of a page, destroying books – especially medieval ones – is bad. However, the cases of recycling shown here also point out how very useful the second life of the manuscript could be. To medieval scribes and post-medieval binders and tailors it must have been a joy to have piles of recyclable parchment books at their disposal. Moreover, to speak as an optimist, their slicing and dicing is proving most useful. Thanks to the destructive practices in the past we at least have some pages or strips left from given manuscripts – which would otherwise have completely disappeared. Seeing a few lines is often enough to identify a text and determine when and where it was copied. In this way fragments become blips on the radar: they add, often significantly, to the study of medieval literary and scholarly culture. While destroying medieval books is bad, it is most useful to have their sorry remains.

Note – More about fragments in bookbindings in this and this post. Take a closer look at a palimpsest here. More on using manuscripts in textiles here.