The Biden administration has recently proposed a global minimum corporate tax, but what is at stake in such a policy? When debating public financial matters, it can be easy to get so focused on economics and politics that basic ethical considerations fade into the background. David Scheffer, for example, notes that when it comes to corporate tax avoidance “much of the ensuing debate has centered on how to tax corporate profits fairly and more efficiently…but there has been little effort to associate tax avoidance schemes with corporate abdication of responsibility for advancing critical societal goals.”

Scheffer was writing in 2013, when Starbucks paid only £8.6 million in British taxes over a 14-year period, and paid no UK corporate taxes in 2011 despite over $400 million in sales. U.S. corporations had $1.7 trillion in overseas accounts to avoid taxes. Apple, for example, held about $100 billion in tax haven accounts to avoid taxation in the U.S. In 2020, despite record-breaking profits, Amazon only paid an effective tax rate of 9.4% rather than the actual 21% rate, avoiding over 2 billion dollars in taxes. (Prior to that, Amazon had avoided paying taxes altogether for several years.) As a result of these trends, Scheffer points out that the percentage of tax revenue collected from wage-earners and consumers has increased dramatically, while the percentage of corporate taxation has dropped precipitously.

Unfortunately, figuring out what to do about the situation is no small task. While a nation can try to close loopholes and raise taxes, a corporation can simply move their corporate headquarters to a different nation with a lower corporate tax rate. These tax havens allow companies to minimize their tax liabilities through profit-shifting; companies register their headquarters in an alternative jurisdiction rather than the country where its sales took place.

To crack down on corporate tax avoidance, the Biden administration is now calling for a global minimum corporate tax rate of at least 15%. As Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen recently stated, a global minimum would “stop what’s been essentially a race to the bottom, so that it’s competitive attractions of different countries that influence location decisions, not tax competition.” The idea is that a country could require a corporation to pay the difference between its minimum tax rate and the rate it pays on earnings in foreign countries.

So far, several nations have signaled their agreement with the proposal. Canada, Germany, France, and many others have indicated their interest, while nations like Ireland and Hungary have registered vocal opposition. (Ireland has only a 12.5% corporate tax rate and has encouraged numerous businesses to create subsidiaries there for years to take advantage of this.) Many developing nations have also expressed misgivings about the proposal due to fears a crackdown will discourage foreign investments.

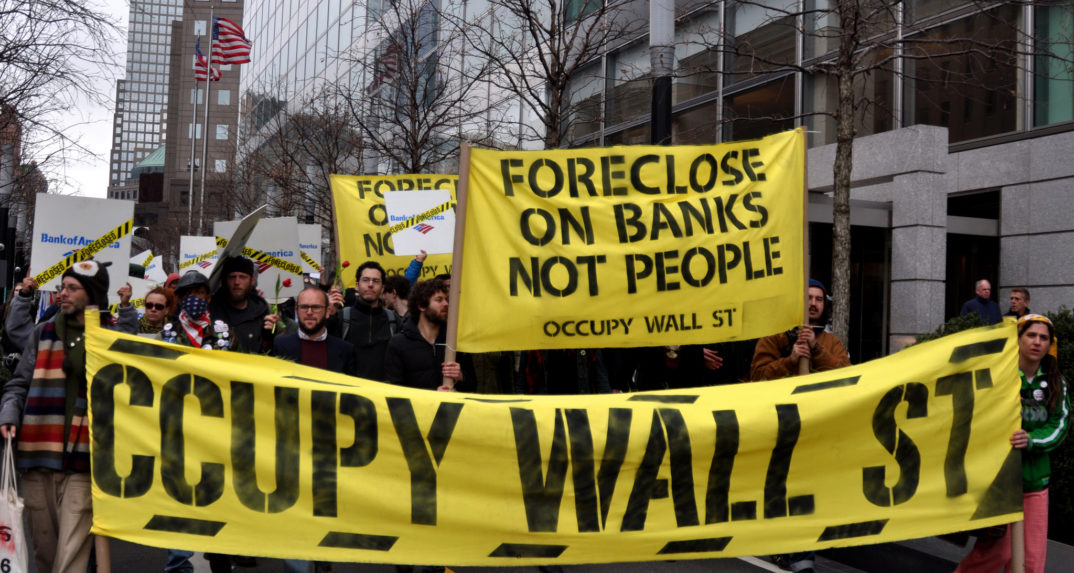

While a global minimum rate may be important for issues of trade and economic development, the issue of tax competition has received comparatively little attention when it comes to issues of ethics and justice. But Peter Dietsch and Thomas Rixen have argued that tax competition undermines the de facto sovereignty of states. Without the ability to effectively set the size of the state budget and the extent of redistribution, states have no fiscal self-determination.

Likewise, Scheffer argues that taxes are a moral issue because the future of human rights depends on a state which is capable of protecting and securing them (and has the funds to do so). Further, while Milton Friedman and others have argued that corporations are primarily only responsible to their shareholders, Scheffer notes that given climate change, rising income disparity, and the backsliding to authoritarianism, there is no such neat division between capitalist pursuits and societal imperatives. He argues:

“The fact that major multinational corporations are paying such comparatively miserly taxes in their home or operating jurisdictions, and doing so legally, means they are minimizing their contributions to social priorities in education, infrastructure, public health care, law enforcement, and even the military defense of countries that provide them with the security and stability that allows them to earn their profit. Societies where these government services are properly financed stand a much better chance of protecting the human rights of the populace.”

Overall, tax avoidance by corporations contributes to the overall decline of government services, which “degrades the operating environment and the very markets within which corporations seek to thrive.” These considerations suggest important moral issues at stake in addressing corporate tax avoidance.

On the other hand, critics of the global minimum corporate rate argue that the move is unfair. While the move would equalize tax rates across the globe, it would also benefit richer nations at the expense of smaller and developing economies who would no longer be able to set lower, more competitive rates to attract foreign investment. Foreign investment represents an integral part of the development plans for lower-income countries, and so the move threatens to reduce the overall welfare of lower-income countries. Even Ireland has managed to dramatically increase living standards after once having one of the worst living standards in Europe, largely thanks to foreign investment. Nations like Mauritius, Paraguay, Uzbekistan, and Kosovo would likely suffer from a decline in tax revenue as well, while a global standard would help nations like the U.S. and France.

But of course, that doesn’t mean that steps couldn’t be taken to mitigate some of these concerns such as direct redistribution of financial means into education and public infrastructure of developing nations. Besides, perhaps taxes should be applied more where economic activity and value creation occurs rather than the location of corporate headquarters. But beyond these practical considerations, Scheffer argues that “the higher ethical perspective” demands that corporations look past minimal standards of compliance and embrace a stronger sense of social corporate responsibility. In order to address the larger problem of which tax competition is merely symptomatic, it’s important to stress the ethical role that corporations have to play in advancing our shared societal goals.