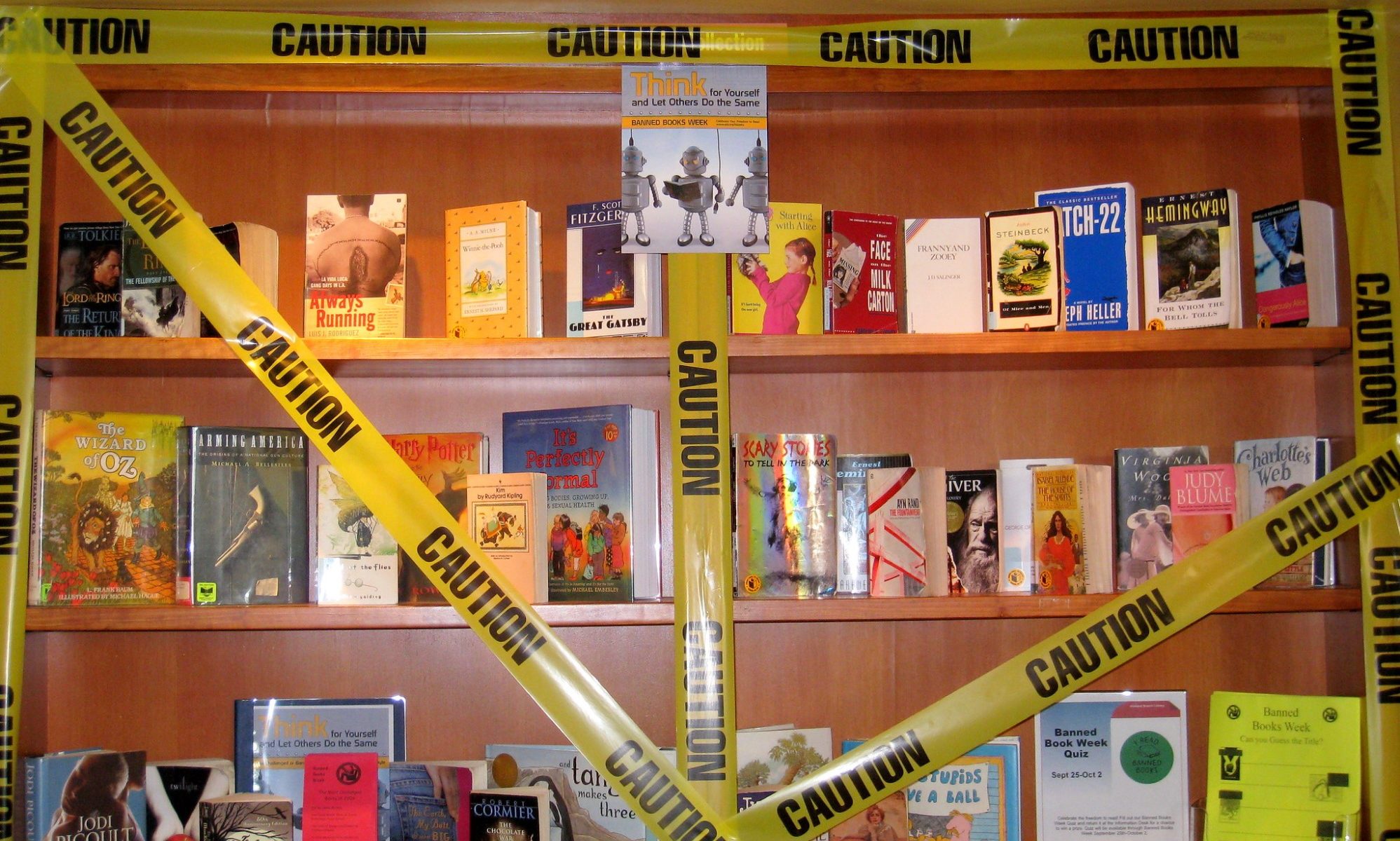

Book bans in public schools are not new in America. But since 2021, they have reached levels not seen in decades, the result of efforts by conservative parents, advocacy groups, and lawmakers who view the availability of certain books in libraries or their inclusion in curricula as threats to their values. In one study that looked at just the nine-month period between July 1, 2021 and March 31, 2022, the free expression advocacy organization PEN America found nearly 1,600 instances of individual books being banned in eighty-six school districts with a combined enrollment of over two million students. Of the six most-banned titles, three (Gender Queer: A Memoir, All Boys Aren’t Blue, and Lawn Boy) are coming-of-age stories about LGBTQ+ youth; two (Out of Darkness and The Bluest Eye) deal principally with race relations in America; and one (Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out) features interviews with transgender or gender-neutral young adults. 41% of the bans were tied to “directives from state officials or elected lawmakers to investigate or remove books.”

The bans raise profound ethical and legal questions that expose unresolved issues in First Amendment jurisprudence and within political liberalism concerning the free speech rights of children, as well as the role of the state in inculcating values through public education.

What follows is an attempt to summarize, though not to settle, some of those issues.

First, the legal side. The Supreme Court has long held that First Amendment protections extend to public school students. In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, a seminal Vietnam War-era case about student expression, the Court famously affirmed that students in public schools do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” Yet student expression in schools is limited in ways that would be unacceptable in other contexts; per Tinker, free speech rights are to be applied “in light of the special characteristics of the school environment.”

Accordingly, Tinker held that student speech on school premises can be prohibited if it “materially and substantially disrupts the work and discipline of the school.”

The Court has subsequently chipped away at this standard, holding that student speech that is not substantially and materially disruptive — including off-campus speech at school-sponsored events — can still be prohibited if it is “offensively lewd and indecent” (Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser), or can be “reasonably viewed as promoting illegal drug use” (Morse v. Frederick). In the context of “school-sponsored expressive activities,” such as student newspapers, the permissible scope for interference with student speech is even broader: in Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, the Court held that censorship and other forms of “editorial control” do not offend the First Amendment so long as they are “reasonably related to legitimate pedagogical concerns.”

Those cases all concerned student expression. A distinct issue is the extent to which students have a First Amendment right to access the expression of others, either through school curricula or by means of the school library. Book banning opponents generally point to a 1982 Supreme Court case, Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District No. 26 v. Pico, to support their argument that the First Amendment protects students’ rights to receive information and ideas and, as a consequence, public school officials cannot remove books from libraries because “they dislike the ideas contained in those books and seek by their removal to prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, and other matters of opinion.”

There are, however, three problems with Pico from an anti-book banning perspective. First, those frequently cited, broad liberal principles belong to Justice Brennan’s opinion announcing the Court’s judgment. Only two other justices joined that opinion, with Justice Blackmun writing in partial concurrence and Justice White concurring only in the judgment. Thus, no majority opinion emerged from this case, meaning that Brennan’s principles are not binding rules of law. Second, even Brennan’s opinion conceded that school officials could remove books from public school libraries over concerns about their “pervasive vulgarity” or “educational suitability” without offending the First Amendment. This concession may prove particularly significant in relation to books depicting relationships between LGBTQ+ young adults, which tend to include graphic depictions of sex. Finally, Brennan’s opinion drew a sharp distinction between the scope of school officials’ discretion when it comes to curricular materials as opposed to school library books: with respect to the former, he suggested, officials may well have “absolute” discretion. Thus, removals of books from school curricula may be subject to a different, far less demanding constitutional standard than bans from school libraries. In short, Pico is a less-than-ideal legal precedent for those seeking to challenge book bans on constitutional grounds.

The question of what the law is is, of course, distinct from what the law should be. What principles should govern public school officials’ decisions regarding instructional or curricular materials and school library books?

A little reflection suggests that the Supreme Court’s struggle to articulate clear and consistent standards in the past few decades may be due to the fact that this is a genuinely hard question.

Political liberalism — the political philosophy that identifies the protection of individual liberty as the state’s raison d’être — has traditionally counted freedom of expression among the most important individual freedoms. Philosophers have customarily offered three justifications for this exalted status. The first two are broadly instrumental: according to one view, freedom of expression promotes the discovery of truth; according to another, it is a necessary condition for democratic self-governance. An important non-instrumental justification is that public expression is an exercise of autonomy, hence intrinsically good for the speaker.

The instrumental justifications seem to imply, or call for, a corresponding right to access information and ideas. After all, a person’s speech can only promote others’ discovery of truth or help others govern themselves if that speech is available to them. Simply having the unimpeded ability to speak would not contribute to those further goods if others were unable to take up that speech.

Yet even if the right of free speech implies a right to access information and ideas, it may be plausibly argued that the case for either right is less robust with respect to children. On the one hand, children generally have less to offer in terms of scientific, artistic, moral, or political speech that could promote the discovery of truth or facilitate democratic self-governance, and since they are not fully autonomous, their speech-acts are less valuable for them as exercises of their autonomy. On the other hand, since children generally are intellectually and emotionally less developed than adults, and also are not allowed to engage in the political process, they have less to gain from having broad access to information and ideas.

Obviously, even if sound, the foregoing argument only establishes lesser rights of free speech or informational access for children, not no such rights. And the case for lesser rights seems far weaker for teenagers than for younger children. Finally, the argument may be undermined by the state and society’s special interest in educating the young, which may in turn provide special justification for more robust free speech and informational access rights for children. I will return to this point shortly.

All the states of the United States, along with the federal government, recognize an obligation to educate American children. To fulfill that obligation, states maintain public schools, funded by taxation and operated by state and local government agencies, with substantial assistance from the federal government and subject to local, state, and federal regulation. As we’ve seen, the Supreme Court has mostly used the educational mission of the public school as a justification for allowing restrictions on students’ free speech and informational access rights inasmuch as their exercise would interfere with that mission.

Thus, the Court deems student speech that would disturb the discipline of the school, or books that would be “educationally unsuitable,” as fair game for censorship.

This is not radically different from the Court’s approach to speech in other public institutional contexts; for example, public employees’ speech is much more restricted than speech in traditional public forums. The combination of the sort of considerations adduced in the last paragraph, together with idea that speech and informational access can be legitimately restricted in public institutions, may lead one to conclude that student expression and informational access in public schools can be tightly circumscribed as long as it is for a “legitimate pedagogical purpose.”

This conclusion would, I think, be overhasty. The overriding pedagogical purpose of the public school does not cleanly cut in favor of censorship; in many ways, just the opposite. Educating students for citizenship in a liberal democracy must surely involve carefully exposing them to novel and challenging ideas. Moreover, mere exposure is not sufficient: the school must also encourage students to engage with such ideas in a curious, searching, skeptical, yet open-minded way. Students must be taught how to thrive in a society replete with contradictory and fiercely competing perspectives, philosophies, and opinions. Shielding students from disturbing ideas is a positive hindrance to that goal. This is not to deny that some content restrictions are necessary; it is merely to claim that the pedagogical mission of the public school may provide reason for more robust student free speech and informational access rights.

But what about conservatives’ objections — I assume at least some of them are made in good faith — to the “vulgarity” of certain books, irrespective of their intellectual content? Their determination to insulate students from graphic descriptions of sex might seem quixotic in our porn-saturated age, and one might think it is no worse than that. In fact, insofar as these objections derive from the notion that it is the job of public schools to “transmit community values,” as Brennan put it in Pico, they raise an important and unresolved problem for political liberalism.

Many versions of political liberalism hold that the state should strive to be neutral between the competing moral perspectives that inevitably exist in an open society.

The basic idea is that for the sake of both political legitimacy and stability, the state ought to be committed to a minimal moral framework — for example, a bill of rights — that can be reasonably accepted from different moral perspectives, while declining to throw its weight behind one particular “comprehensive doctrine,” to use John Rawls’s phrase.

For example, it would be intuitively unacceptable if state legislators deliberated about the harms and benefits of a particular policy proposal in terms of whether it would please or enrage God, or of its tendency to help the public achieve ataraxia, the Epicurean goal of serene calmness. One explanation for this intuition is that such deliberation would violate neutrality in employing ideas drawn from particular comprehensive doctrines, whether secular or religious, that are not part of that minimal moral framework with which most of the public can reasonably agree.

If state neutrality is a defensible principle, it should also apply to public education: the state should not be a transmitter of community values, at least insofar as those values are parochial and “thick,” rather than universal and “thin.” Concerns about children’s exposure to graphic depictions of sex may be grounded in worries about kinds of harm that everyone can recognize, such as psychological distress or, for certain depictions, the idea that they encourage violent sexual fantasies that might later be enacted in the real world. But conservatives’ worries might also be based in moral ideas that don’t have much purchase in the liberal moral imagination — ideas about preserving sexual purity or innocence, or about discouraging “unnatural” sexual conduct like homosexuality. These ideas, which are evidently not shared by a wide swath of the public, do not have a place in public education policy given the imperative of state neutrality.

Unfortunately, while perhaps intuitively compelling, the distinction between an acceptably “minimal” moral framework and a “comprehensive doctrine” has proved elusive. For example, are views about when strong moral subject-hood begins and ends necessarily part of a comprehensive doctrine, or can they be inscribed in the state’s minimal moral framework? Even if state neutrality can be adequately defined, many also question whether it is desirable or practically possible. Thus, it remains an open question whether the transmission of parochial values is a legitimate aim of public education.

Public educators’ role in mediating between students and the universe of ideas is and will likely remain the subject of ongoing philosophical and legal debate. However, this much seems clear: conservative book bans are just one front in a multi-front struggle to reverse the sixty-year trend of increasing social liberalization, particularly in the areas of sex, gender, and race.