On June 17th, Lee Sanderlin walked into a Waffle House in Jackson, Mississippi; fifteen hours later, he walked out an internet sensation. As a penalty for losing in his fantasy football league, Sanderlin’s friends expected him to spend a full day inside the 24-hour breakfast restaurant (with some available opportunities for reducing his sentence by eating waffles). When he decided to live-tweet his Waffle House experience, Sanderlin could never have expected that his thread would go viral, eventually garnering hundreds of thousands of Twitter interactions and news coverage by outlets like People, ESPN, and The New York Times.

For the last half-decade or so, the term ‘fake news’ has persistently gained traction (even being voted “word of the year” in 2017). While people disagree about the best possible definition of the term (should ‘fake news’ only refer to news stories intentionally designed to trick people or could it countenance any kind of false news story or maybe something else?), it seems clear that a story about what Sanderlin did in the restaurant is not fake: it genuinely happened, so reporting about it is not spreading misinformation.

But that does not mean that such reporting is spreading newsworthy information.

While a “puff piece” or “human interest story” about Sanderlin in the Waffle House might be entertaining (and, by extension, might convince internet users to click a link to read about it), its overall value as a news story seems suspect. (The phenomenon of clickbait, or news stories marketed with intentionally noticeable headlines that trade accuracy for spectacle, is a similar problem.) Put differently, the epistemic value of the information contained in this news story seems problematic: again, not because it is false, but rather because it is (something like) pointless or irrelevant to the vast majority of the people reading about it.

Let’s say that some piece of information is newsworthy if its content is either in the public interest or is otherwise sufficiently relevant for public distribution (and that it is part of the practice of good journalism to determine what qualifies as fitting this description). When the president of the United States issues a statement about national policy or when a deadly disease is threatening to infect millions, then this information will almost certainly be newsworthy; it is less clear that, say, the president’s snack order or an actor’s political preferences will qualify. In general, just as we expect their content to be accurate, we expect that stories deemed worthy to be disseminated through our formal “news” networks carry information that news audiences (or at least significant subsets thereof) should care about: in short, the difference between a news site and a gossip blog is a substantive one.

(To be clear: this is not to say that movie releases, scores of sports games, or other kinds of entertainment news are not newsworthy: they could easily fulfill either the “public interest” or the “relevance” conditions of the ‘newsworthy’ definition in the previous paragraph.)

So, why should we care about non-newsworthy stories spreading? That is to say, what’s so bad about “the paper of record” telling the world about Sanderlin’s night in a Mississippi Waffle House?

Two problems actually come to mind: firstly, such stories threaten to undermine the general credibility of the institution spreading that information. If I know that a certain website gives equal attention to stories about COVID-19 vaccination rates, announcements of Supreme Court decisions, Major League baseball game scores, and crackpots raging about how the Earth is flat, then I will (rightly, I think) have less confidence that the outlet is capable of reporting accurate information in general (given its decision to spread demonstrably false conspiracy theories). In a similar way, if an outlet gives attention to non-newsworthy stories, then it can water down the perceived import of the other genuinely newsworthy stories that it typically shares. (Note that this problem is compounded further when amusing non-newsworthy stories spread more quickly on the basis of their entertaining quirks, thereby altering the average public profile of the institution spreading them.)

But, secondly, non-newsworthy stories pose a different kind of threat to the epistemic environment than do fake news stories: whereas the latter can infect the community with false propositions, the former can infect the community with bullshit (in a technical sense of the term). According to philosopher Harry Frankfurt, ‘bullshit’ is a tricky kind of speech act: if Moe knows that a statement is false when he asserts it, then Moe is lying; if Moe doesn’t know or care whether a statement is true or false when he asserts it, then Moe is bullshitting. Paradigmatically, Frankfurt says that bullshitters are looking to provoke a particular emotional response from their audience, rather than to communicate any particular information (as when a politician uses rhetoric to affectively appeal to a crowd, rather than to, say, inform them of their own policy positions). Ultimately, Frankfurt argues that bullshit is a greater threat to truth than lies are because it changes what people expect to get out of a conversation: even if a particular piece of bullshit turns out to be true, that doesn’t mean that the person who said it wasn’t still bullshitting in the first place.

So, consider what happened when an attendee at a campaign rally for Donald Trump in 2015 made a series of false assertions about (among other things) Barack Obama’s supposedly-foreign citizenship and the alleged presence of camps operating inside the United States to train Muslims to kill people: then-candidate Trump responded by saying:

“We’re going to be looking at a lot of different things. You know, a lot of people are saying that, and a lot of people are saying that bad things are happening out there. We’re going to look at that and plenty of other things.”

Although Trump did not clearly affirm the conspiracy theorist’s racist and Islamophobic assertions, he nevertheless licensed them by saying that “a lot of people are saying” what the man said. Notice also that Trump’s assertion might or might not be true — it’s hard to tell how we would actually assess the accuracy of a statement like “a lot of people are saying that” — but, either way, it seems like the response was intended more to provoke a certain affective response in Trump’s audience. In short, it was an example of Frankfurtian bullshit.

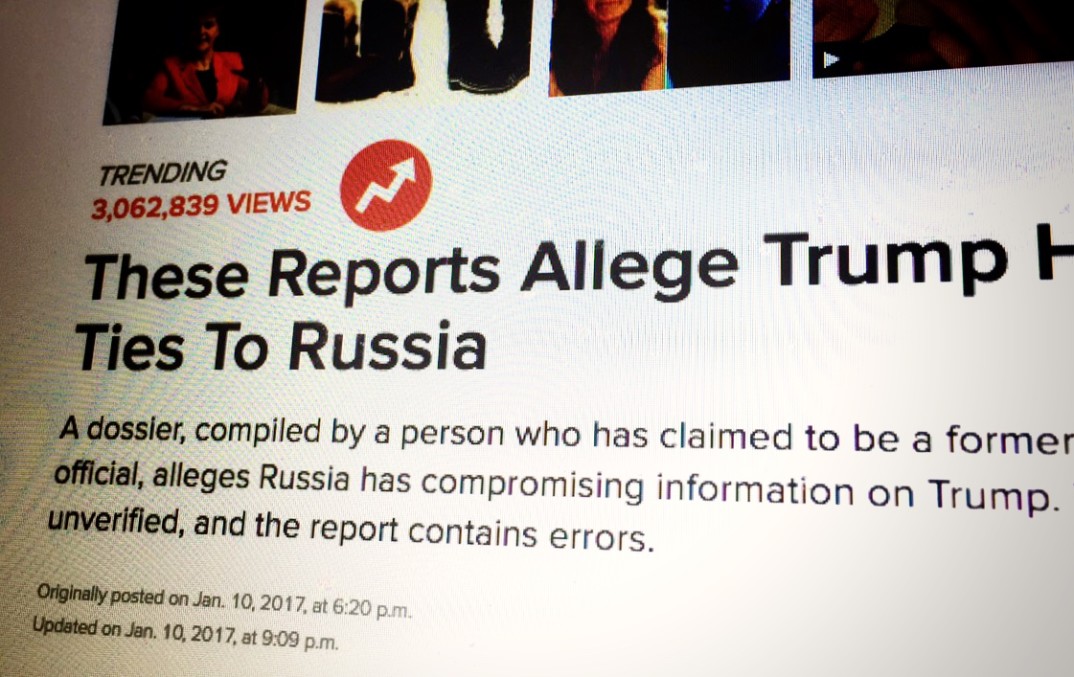

Conspiracy theories about Muslim “training camps” or Obama’s unAmerican birthplace are not newsworthy because, among other things, they are false. But a story like “Donald Trump says that “a lot of people are saying” something about training camps” is technically true (and is, therefore, not “fake news”) because, again, Trump actually said such a thing. Nevertheless, such a story is pointless or irrelevant — it is not newsworthy — there is no good reason to spread it throughout the epistemic community. In the worst cases, non-newsworthy stories can launder falsehoods by wrapping them in the apparent neutrality of journalistic reporting.

For simplicity’s sake, we might call this kind of not-newsworthy story an example of “dog-wagging news” because, just as “the tail wagging the dog” evokes an image where the “small or unimportant entity (the tail) controls a bigger, more important one (the dog),” a dog-wagging news story is one where something about the story other than its newsworthiness leads to its propagation throughout the epistemic environment.

In harmless cases, dog-wagging stories are amusing tales about Waffle Houses and fantasy football losses; in more problematic cases, dog-wagging stories help to perpetuate conspiracy theories and worse.