The more intelligent an organism is, the more issues come with its captivity and, specifically, with its farming. Few lament carrot cultivation because vegetables are unintelligent and cannot suffer. Insects are more challenging as they respond to stimuli. Still, there is doubt whether they possess the required biological mechanisms to feel pain meaningfully. Domestic mammals are an even more significant challenge as their biology resembles ours enough to cast doubt on whether breeding and slaughtering them for food is permissible. Even more problematic are great apes, which, while not commonly bred for consumption, present severe challenges regarding humane treatment and enrichment in captivity. Finally (and hopefully theoretically), farming humans is strictly morally and legally prohibited because it would be principally and practically impossible to do so (putting aside the fact that we shouldn’t harm one another ipso facto). As Jeremy Bentham put more succinctly in An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, when considering how to treat others, be they human or otherwise, “The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?”

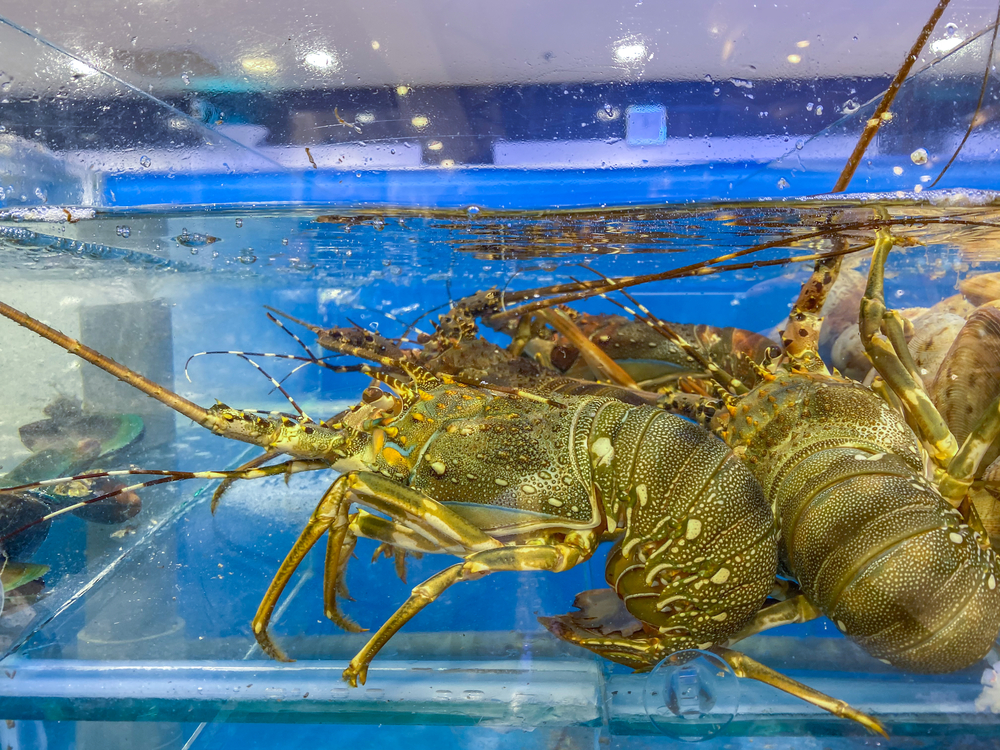

This link between intelligence and farming underpins the outrage by animal rights groups at Nueva Pescanova’s plans for the world’s first octopus farm in Spain’s Canary Islands. Demand for such a facility certainly exists; many around the globe consider octopus a delicacy. But, until recently, successful octopus breeding had proven impossible to achieve commercially. Wild-caught octopuses were the only source. However, the company announced in 2019 that it managed to overcome the traditional hurdles that had prevented octopus breeding and was ready to proceed. As animal breeding is generally more straightforward and profitable than hunting and fishing, the venture stands to make Nueva Pescanova a lot of money.

But, unlike carrots, octopuses are not passive organisms unable to suffer. In fact, scientists typically consider octopuses highly intelligent, demonstrating a remarkable capacity for problem-solving and deep curiosity. For example, in 2009, workers at the Santa Monica Pier Aquarium arrived to find that one of their octopuses had redirected 200 gallons of seawater from its tank to the floor outside. They’re even capable of unscrewing jars to gain access to food within, which they complete faster each time scientists present them with the challenge. Indeed, as the 2020 hit film My Octopus Teacher revealed to many, octopuses are vastly complex organisms that play, mimic, and learn.

It is this capacity for intelligence and curiosity – one so remarkable that octopuses are the only invertebrate protected by the U.K.’s Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act of 1986 – that has led to the outrage about the planned octopus farm. According to a report by Eurogroup For Animals and Compassion in World Farming, the proposed facility will house and kill over a million octopuses yearly. This is a pretty horrifying statistic (although it pales compared to the roughly 890,000 cattle slaughtered daily in 2019). But, the conditions in which the octopuses will live and die give that number an even grimmer context.

First, according to the report, workers will kill the octopuses by submerging them into an ice slurry of around -3°C. Unfortunately, when used to kill fish, this method results in a slow and painful death (for more on the ethics of fish consumption, see The Prindle Post article on The Feelings of Fish). There is little reason to think this would be any different for octopuses. Indeed, given the octopuses’ remarkable cognitive capabilities, which exceed that of most fish, there’s reason to believe such a death would be even more agonizing.

Second, octopuses are, for the most part, solitary creatures. They prefer to live alone and only interact with others of their species at specific moments (like when mating). However, housing each octopus separately would be logistically and financially impossible at a commercial farm. So, Nueva Pescanova plans to keep its stock grouped in multiple tanks, with roughly ten to fifteen octopuses per cubic meter. For a solitary species, this is a recipe for a poor quality of life, and it runs the risk of leading to cannibalism. So, not only will they be housed amongst others of their species, for which they aren’t evolved, but they’ll also have to contend with the risk of predation.

Third, Nueva Pescanovaplan will keep the octopuses under 24-hour light to enhance captive females’ breeding capacity. Of course, this would be uncomfortable and likely traumatic for any number of creatures. Still, the prospect is practically hellish for octopuses that spend much of their time in the dark and can feel light via sensors in their many arms.

These are just a snippet of the concerns the farms raise. But, it paints a pretty unpleasant picture of a solitary, intelligent species forced into intimate proximity with others of its kind, for its entire life, under the gaze of 24-hour lights, until they reach a harvestable size when they’re dunked into sub-zero water to die. The company has acknowledged these worries and claims it will work to mitigate them. However, it is hard to see how Nueva Pescanova can accomplish this when the welfare concerns are in such stark contrast with the company’s proposed operating practices. And, if traditional agriculture and farming practices are any example, we can expect animal welfare to take a backseat to monetary interests.

In determining our obligations and responsibilities to others, Bentham asks us to consider whether an organism can suffer. If so, then we owe that creature the rights traditionally reserved for humans. So, would we feel comfortable treating humans in this way? The answer (hopefully) is no. If octopuses can suffer in a way that, while not identical to us, is at least comparable, then we have to ask whether such farming should be allowed.

While overwhelmingly dark, this story has a thin sliver of light. There are already bills progressing through Washington state’s House to prevent similar farms from being established there. While House Bill 1153 focuses on the environmental impacts (which is a good thing to focus on), it does make some allusion to the horrors that await farmed octopuses. Sadly, however, while this does offer some hope, it will come as cold comfort to those octopuses that could eventually be farmed in inhumane conditions around the rest of the world.

Ultimately, in the face of today’s all-consuming capitalistic practices, the question isn’t whether animals can suffer but whether their suffering can be made profitable.