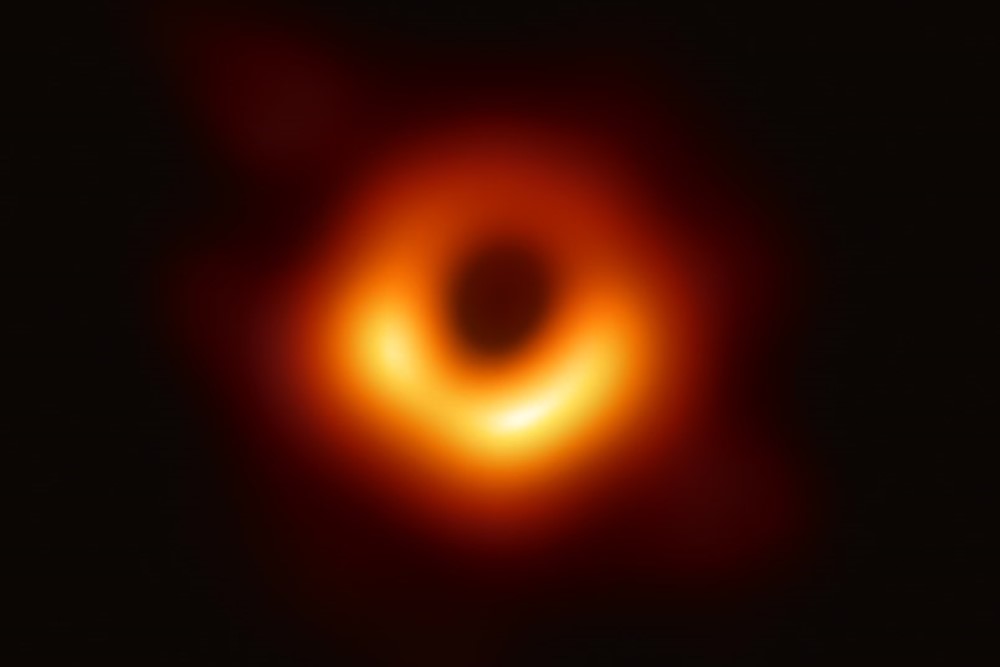

Astronomers at the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration recently released the first picture of Sagittarius A*, the monstrous black hole residing at our galaxy’s core. Given that the distance between the Earth and this cosmological object is roughly 26,000 light-years (or 152,844,259,702,773,792 miles), the image’s production is a remarkable scientific and technological achievement. While Sgr A*, as it is affectionately known, weighs 4 million times the mass of our sun, it is only 17 times its size. This combination of mass and size results in gravitational forces strong enough to shape the entire Milky Way galaxy and warp existence itself – bending space, altering the flow of time, and preventing even light from escaping.

This isn’t the first time the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration has produced such an awesome image.

In 2019, the array captured the very first image of a black hole. This one, named M87*, resides in the center of another galaxy roughly 500 million light-years away (or 2,939,312,686,591,800,000,000 miles). With a mass 6.5 billion times that of our sun and measuring over 23 billion miles across, M87* dwarfs Sgr A*. For a sense of scale, the distance from the Sun to Neptune, the most distant planet in our solar system, is 3 billion miles. Indeed, this M87* is thought to be one of the largest black holes in existence.

These objects’ sheer scale and weight, alongside their distance from us, defy comprehension. And while black holes are undoubtedly unique celestial objects, much of the universe plays out on an equally impressive scale. Planets, galaxies, stars, and quasars, amongst numerous other cosmological objects, exist on geographical and temporal scales far beyond anything on Earth. Asking someone to comprehend a single object vastly larger than our entire solar system is to ask them to conceive of the inconceivable.

We’re just not evolved to think about reality in such grand terms. As corporeal beings, limited to a single planet and a single lifetime, we think in human terms; we’re geared to understand the universe on our scale.

But regardless of this predisposition, the universe is beyond vast. The cosmic scale on which existence plays out makes everything that’s occurred here on Earth, from the first hints of life to you reading this sentence, seem infinitesimally small in comparison. Existence’s sheer unassailability can fill the heart with dread as it means that the universe is, by its nature, incomprehensible. That is, as limited, mortal beings, the overwhelming majority of existence will forever be home to the unknowable and the unknown, and nothing stokes fear like the unknown.

This fear, and specifically its emergence from the universe’s vast and uncaring nature, was a central theme in the fiction of Howard Phillips Lovecraft, AKA HP Lovecraft. Indeed, many of his most famous stories – The Shadow over Innsmouth, At the Mountains of Madness, and Colour out of Space – concern a small group of persons wrestling with their insignificance in the face of a vastly uncaring universe. While his fiction features creatures literally beyond comprehension (just seeing some of them drives characters into insanity), these beings always function as embodiments of the irrefutable fact that our fleeting lives mean less than nothing in the grand terms of space and time.

As Lovecraft writes in the opening to arguably his most famous work, The Call of Cthulhu:

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

Many philosophies and religions focus on humanity. They ascribe to us some vital place in God’s design, use rationality to construct a coherent worldview, or provide frameworks according to which we can understand right and wrong. But Lovecraft sought to set the scope of his philosophy, known as Cosmicism, beyond our limited mortal perspective. For him, there is simply so much out there in the universe that has nothing to do with us. For humanity to try and come to grips with reality in its entirety is to attempt an impossible task, one that would shatter our minds if even partially achieved. Cosmicism highlights that while things may matter to us on a human scale, this scale is meaningless compared to reality’s vastness. In other words, while things matter to us, ultimately, we don’t matter.

This realization may strike readers, even atheistic ones, as inherently bleak.

While one can grapple with the idea that existence is godless and that meaning is self-created, that is a very different thing from saying the universe, by its very constitution, is geared against our continued existence due to its utter indifference; much like how a boot is geared against the existence of an ant.

But such an upsetting outcome need not be the only takeaway from Cosmicism. One can read Lovecraft’s works, contemplate existence’s vast and uncaring nature, and be even more thankful for the beauty in our lives. If contradictions and comparisons enhance qualities and characteristics – if good is only good when compared to bad, if hot is only hot when compared to cold – then the earthly things that bring meaning to people’s lives might be even more meaningful when we acknowledge how much of a miracle it is that they exist in the first place. When objects exist, like black holes, that could tear apart the planet in less than a moment, the fact that our meager mortal lives occur as they do seems even more miraculous.

The fact that there is a single, small, blue ball floating in the blackness of space and time, where beauty and meaning (even if that is only according to human standards) can be found amongst existence’s indifferent gaze, should temper our fear of the endless well of the universe… if only a little.