This piece is part of an Under Discussion series. To read more about this week’s topic and see more pieces from this series visit Under Discussion: “Woke Capitalism.”

Many have started to abandon the usage of the term “woke” since it is more and more used in a pejorative sense by ideological parties – as Charles M. Blow states “‘woke’ is now almost exclusively used by those who seek to deride it, those who chafe at the activism from which it sprang.” What the term refers to has become increasingly ambiguous to the point that it seems useless. As early as 2019, Damon Young was suggesting that “woke floats in the linguistic purgatory of terms coined by us that can no longer be said unironically,” and David Brooks concluded that no small part of wokeism was simply the intellectual elite showing off with “sophisticated” language.

But when the term rose to popularity in 2016, it was referring to a kind of awareness of public issues, and “became the umbrella purpose for movements like #blacklivesmatter (fighting racism), the #MeToo movement (fighting sexism, and sexual misconduct), and the #NoBanNoWall movement (fighting for immigrants and refugees).” And new fronts are always opening up.

Discussions of “Woke Capitalism” tend to focus on corporate and consumer activism. Tyler Cowen has also pointed out the importance of wokeism as a new, uniquely American cultural export that may fundamentally change the world. And, indeed, despite the post-mortems, “woke” remains in the lexicon of both political parties.

Even though the term “woke” has fallen out of favor, I suspect there is a mostly unaddressed aspect of wokeism that needs reconsideration. There may very well be a new mode of consumption just beginning to dominate the market: commodities as moral entities.

How does this happen? Let’s consider what differentiates Woke Capitalism from more familiar moral considerations about market relations and discuss how products have become moral entities through comparison to non-woke products.

It is not just about moral considerations: In any decision-making process, it is natural for some moral considerations to arise. In the case of market relations, any number of factors – the company’s affiliations, its production methods, the status of workers, the trustworthiness of the company, etc. – may prove decisive. Traditionally, as in the case of moral appeal in marketing – “If you are a good parent, you should buy this shoe!” – there seems to be a necessity to link a moral consideration with a company or a product. With Woke Capitalism, this relation is transformed: an explicit link is no longer necessary. All purchasing is activism – one cannot help but make a statement with what they choose to buy and what they choose to sell.

It is not just corporate or consumer activism: The moral debate about Woke Capitalism mainly revolves around the sincerity of companies and customers in support of social justice causes. And that discussion of corporate responsibility often revisits the Shareholder vs. Stakeholder Capitalism distinction.

Corporate or consumer activism seems to be making use of the market as a way of demonstrating the moral preferences of individuals or a group. It can be seen as a way to support what is essentially important to us. Vote with your dollar. As such, most discussions focus on this positive reinforcement side of Woke Capitalism.

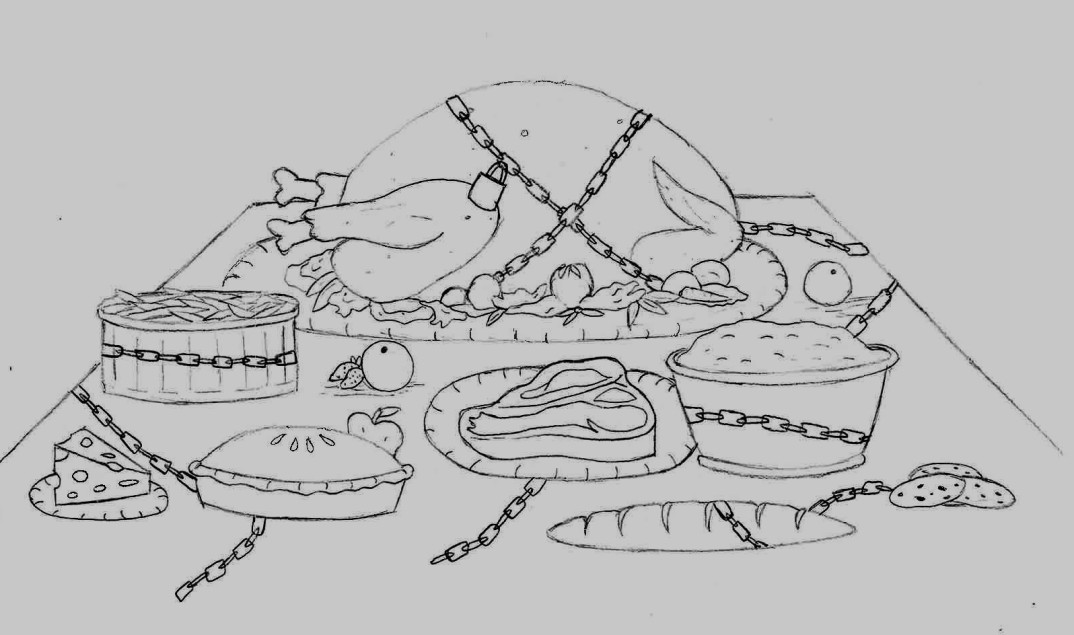

What is lost in this analysis of Woke Capitalism, however, is the production of Woke Products which forces consumers take sides with even the most basic day-to-day purchases.

How should we decide between two similarly-priced products according to this framing: a strong stain remover or a mediocre stain remover that helps sick children; a gender-equality supporting cereal or a racial-equality supporting cereal. Each of these decisions brings some imponderable trade-off with it: What’s more important – the health of children or stain-removing strength? Which problem deserves more attention – gender inequality or racial inequality?

Negation of Non-Woke: The main problem with these questions is not that some of them are unanswerable, absurd, or impossible to decide in a short time. Instead, the problem is the potential polarizing effect of its relational nature. Dan Ariely suggests, in his book Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shapes Our Decisions, that we generally decide by focusing on the relativity – people often decide between options on the basis of how they relate to one another. He gives the example of three houses which have the same cost. Two of them are in the same style. One is a fixer-upper. In such a situation, he claims, we generally decide between the same style houses since they are easier to compare. In this case, the alternatively-styled house will not be considered at all.

In the case of wokeness, the problem is that it is quite probable that non-woke products will be ignored altogether. With our minds so attuned to the moral issue, all other concerns fade away.

Woke Capitalism creates a marketplace populated entirely by woke, counter-woke, and anti-woke products. Market relations continue to be defined by this dynamic more and more. As such, non-woke products are becoming obsolete. Companies must accommodate this trend and present themselves in particular ways, not necessarily because they want to, but because they are forced to. And this state of affairs feels inescapable; there is no breaking the cycle. Even anti-woke and counter-woke marketing feed that struggle. All consumption becomes a moral statement in a never-ending conflict.

To better see what makes Woke Capitalism unique (and uniquely dangerous), consider this comparison:

Classic moral consideration: Jimmy buys Y because Y conforms to his moral commitments.

Consumer activism: Jimmy buys Y because Y best signals his support for a deeply-held cause.

Woke Capitalism: Jimmy buys Y because purchasing products is necessary for his moral identity.

This is not just consumer activism whereby customers seek representation. Instead, commodities turn into fundamentally moral entities – building blocks for people to construct and communicate who they are. As morality becomes increasingly understood in terms of one’s relationship to commodities, a moral existence depends on buying and selling. Consumption becomes identity. “I buy, therefore – morally – I am.”