In the wake of nationwide protests against racial discrimination by the police, politicians and activists in a number of American cities have called for the removal of monuments to Confederate leaders from public spaces. The U.S. military even expressed its willingness to rename military bases named after Confederate generals. Some activists took matters into their own hands, toppling statues or defacing them with red-painted slogans and symbols.

Supporters of removal argue that Confederate monuments harm people of color by conveying messages of support for white supremacy. Critics allege that there is a slippery slope from Confederate figures to the Founding Fathers or Abraham Lincoln. They also claim that removing monuments is tantamount to an Orwellian erasure of history, the sort of practice one would expect in totalitarian regimes, not democracies. So, what should we do with the statues?

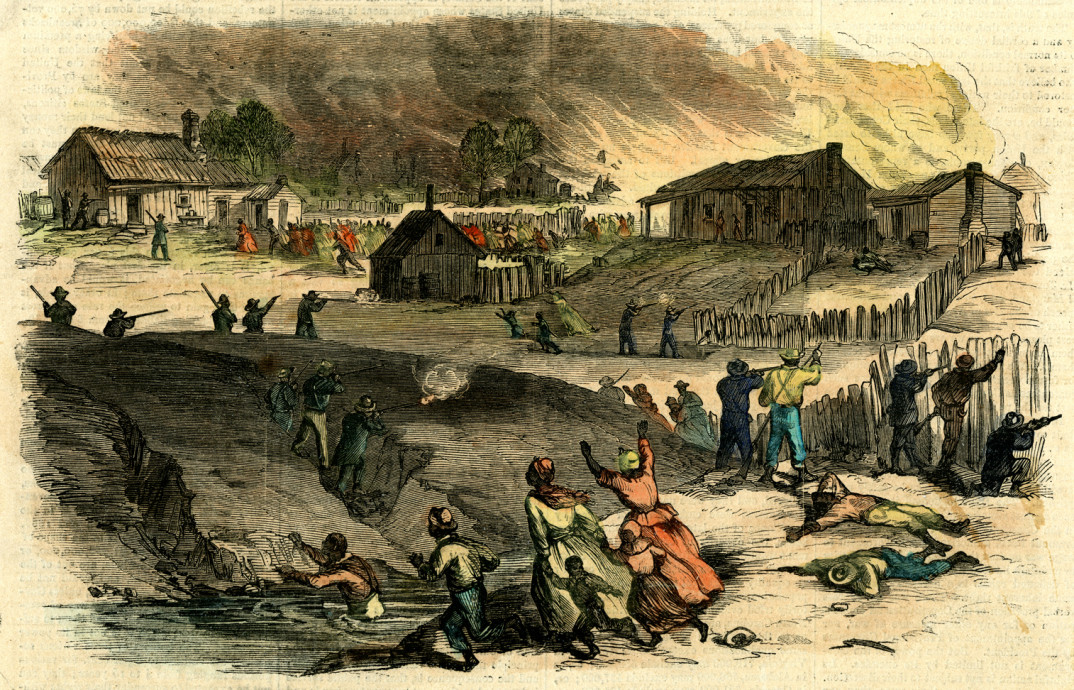

Let’s examine the arguments in greater detail. The argument that Confederate monuments harm people of color is based on a claim about what the monuments mean, or what messages they convey. The intentions of their creators are a particularly important source of their meaning, since they determine such basic facts as what and whom they represent, as well as the values they express. Most monuments to the Confederacy were erected either in the wake of Reconstruction or during the Civil Rights movement, when African-Americans in the South were agitating for greater political power and social equality, and they were intended to express opposition to these developments. Even apart from this history, monumental, idealized depictions of leaders of a state dedicated to the perpetuation of racial slavery are reasonably interpreted as endorsements of the values the Confederacy embodied. And when these monuments are sited on public land, as most are, this can be reasonably interpreted as conveying the endorsements of the public and the state.

Why does this matter? As the philosopher Jeremy Waldron points out, public art and architecture are important means by which society and government can provide assurances to members of vulnerable groups that their rights and constitutional entitlements will be respected. Such assurances are an important part of people’s sense of safety and belonging. But when the public art of a society instead conveys endorsements of subordination and discrimination, this robs members of vulnerable groups of these assurances, transforming the public world into a hostile space and encouraging withdrawal into the private sphere. Thus, vulnerable groups that are intimidated by monuments that express approval for their subordination may be less able to advance their political, social, and economic interests. Importantly, none of these baneful consequences turn on anyone’s being merely offended by racist monuments.

What about the claim that tearing down Confederate monuments will inevitably lead to the removal of monuments to the Founders and other beloved figures? There is a kernel of truth to this argument: questioning the appropriateness of honoring Confederates likely will lead to questioning society’s attitudes towards other historical figures. But it is not clear that this should not happen. At the same time, there are morally relevant differences between some historical figures and others. For this reason, reducing the harms caused by monumental depictions of some historical figures need not always require removing them from public space. What government needs to do with respect to those monuments it wishes to keep on public display is (1) forthrightly acknowledge the problematic aspects of a historical figure’s legacy; (2) endeavor to reduce the harms that might be caused by the monument; and (3) provide an adequate justification for not removing the monument from the public space. For example, while Abraham Lincoln’s actions towards Native Americans were reprehensible on the whole, there is a good case for honoring those aspects of his legacy that continue to inspire citizens of all backgrounds. Yet the less honorable episodes of his presidency ought to be acknowledged alongside celebrations of his achievements.

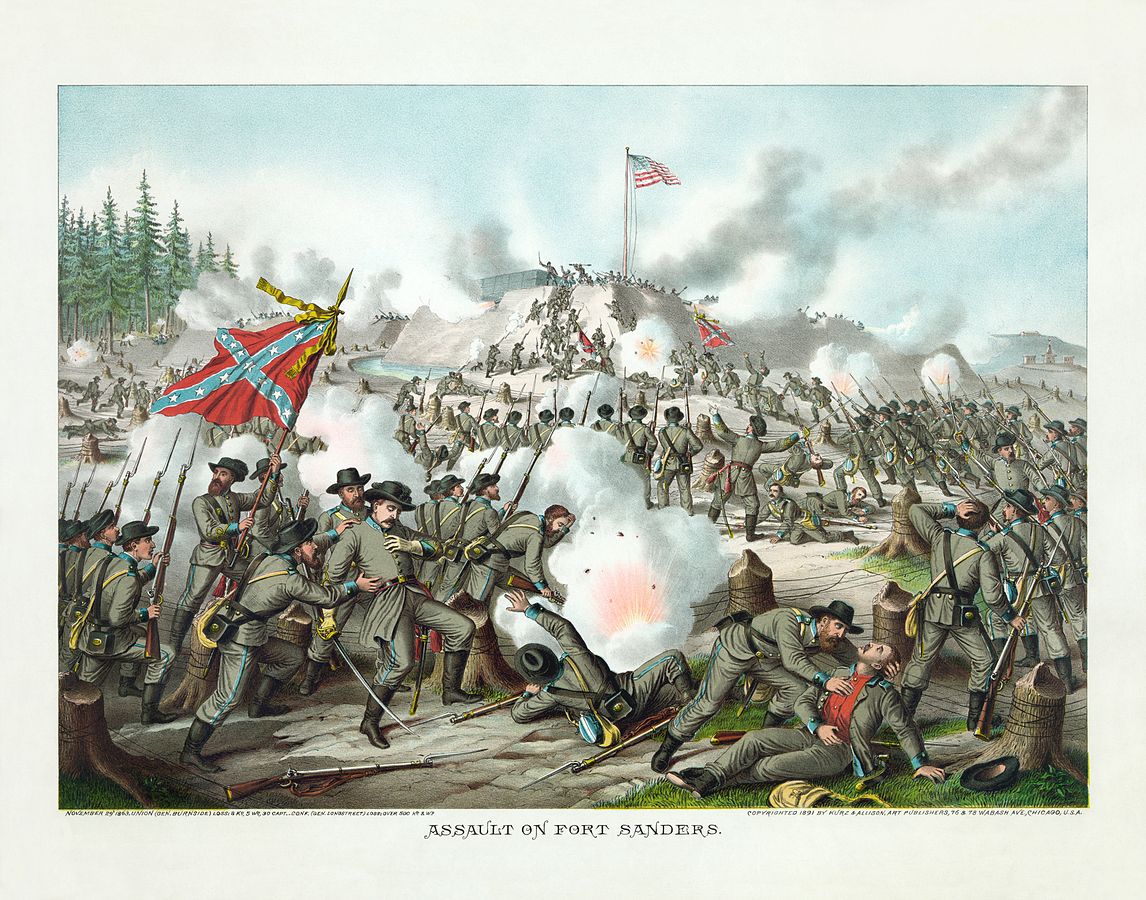

Some claim that removing monuments constitutes an erasure of history, comparing it to burning books. If “erasing history” simply means “destroying something that existed in the past,” tearing down a monument erases history in precisely the same way as tearing down an old house. But as this example suggests, there are many cases of erasing history that seem morally unobjectionable, and the mere fact that something from the past will cease to exist is not in itself a reason to preserve it. Opponents of taking down the monuments sometimes argue that they teach us important lessons about our shared history. This argument at least offers a reason why it might be desirable to preserve this particular class of objects. The trouble is that the story they tell is often distorted and misleading precisely because they were intended not to educate, but to intimidate one group of citizens and cultivate admiration for the Confederacy in another. Monuments are more like billboards than books. Museums can educate the public more effectively than monuments, and without the negative consequences described above. Indeed, in some cases, monuments have found new homes in museums, where they can be properly contextualized for public consumption.

As Americans continue to grapple with their history, it seems likely that monuments to the Confederacy will not be the last lapidary victims of our historical reappraisals. But at least with respect to Confederate monuments, public opinion is coming around to the fact that this is a necessary and justified concomitant of the effort to make our society more equal and more just.