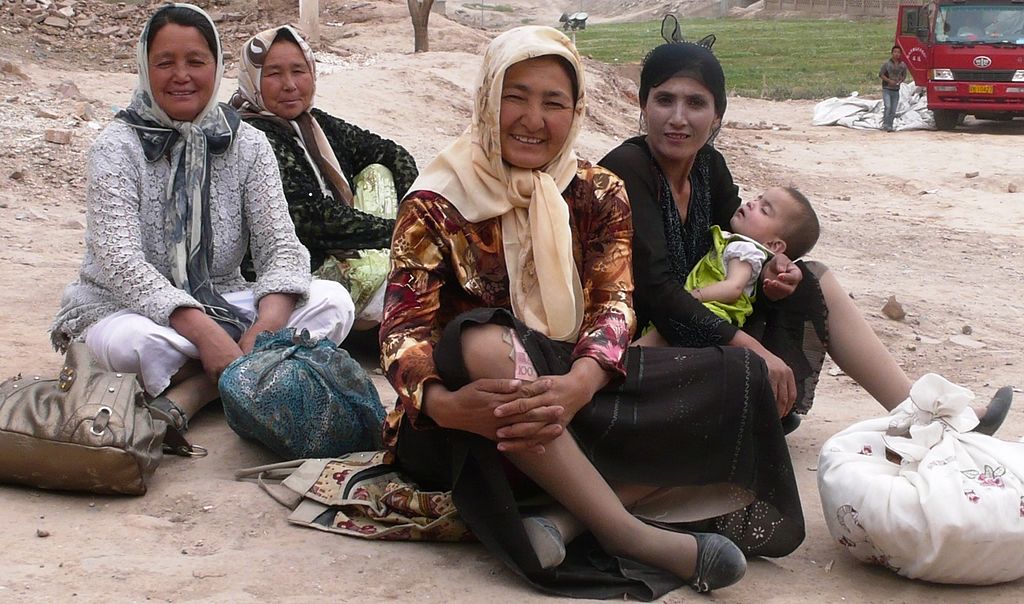

An AP investigation has confirmed complaints from Uighur women that China has been sterilizing them against their will, and in fact discovered that these assaults have been more widespread than previously thought.

Since 2016, an estimated 1 million or more Uighurs have been detained in “re-education” camps. The new investigation highlights the relationship between pregnancy, fertility, and the threat of the camps: “Uighur women and other ethnic minorities are being threatened with internment in the camps for refusing to abort pregnancies that exceed birth quotas [….] Women who had fewer than the legally permitted limit of two children were involuntarily fitted with intrauterine contraceptives.”

By interfering with the reproductive choices of the potential parents, the Chinese government is interfering with the bodily integrity of individuals, and thus violating basic moral principles and fundamental human rights. China is specifically targeting a particular ethnic group with a policy that infringes on individuals’ reproductive autonomy. These acts constitute genocide according to the United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect.

The first morally problematic feature of China’s policies is also the most commonplace and simple: government representatives are acting on members of the community against their will. This infringement of bodily autonomy is assault. There are a very limited number of situations where it is permissible to interfere with someone’s body absent consent, but these cases clearly do not qualify. Moreover, these policies interfere with people’s private desires regarding the formation of a family unit. Family identity and relationships can inform a great deal of one’s priorities and self-understanding; to take those relationships, networks, and choices away from individuals is a particular kind of harm.

Secondly, it is clear that these policies are a further element of oppression towards a population that China has been systematically disadvantaging for years. Uighurs in China have been isolated, surveilled, put into work and re-education camps, and exposed to varieties of mental and physical harms. The group subject to these forced sterilizations has been the target before of racist, bigoted policies aimed at affecting its population and the promulgation of its community in the future.

Given these policies aims and outcomes, China actions constitute genocide against the Uighurs. Many consider genocide to be limited to violent killings with the intent to eliminate an ethnic, racial, or religious minority, as in Myanmar (against Rohingya) in 2016 and again in 2018, or in Somalia (against Isaaqs)1987-8, in Rwanda (against Tutsis) 1994, in Bosnia (against Bosniaks) 1995, by ISIL (against Yazidis) 2014…. However, there are more ways to eliminate a group of people beyond presenting its members with a violent death.

Given that the act of sterilization is targeted towards an unwanted, oppressed community and, by its nature, serves to prevent births in the group and thereby limit its future population, China’s forcible sterilization of members of the Uighur population represents an act of genocide. As the United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect states, “In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group, as such: …d. imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group.”

China is far from the first government body that has used the interference and control of reproduction, or the breaking down of the family unit, as a way to undermine or even eliminate an ethnicity or cultural group. Recent examples include:

- In the fall of 2018, a group of Indigenous Canadian women filed a class-action suit against Saskatoon Health Authority, the provincial and federal governments, and some medical professionals claiming that doctors forcibly sterilized them over several decades, through the 2000s.

- In the United States in the 20th century, 20,000 the government funded sterilizations performed in California disproportionately targeting African Americans and Latinos.

- Further, California prisons have authorized sterilizations of nearly 150 female inmates between 2006 and 2010. The state paid doctors $147,460 to perform tubal ligations that former inmates say were done under coercion.

- In 2003, an investigative report documented grave human rights violations against Romani women in Slovakia, that 110 Romani women in Slovakia were forcibly or coercively sterilized, or had strong indications that they had been sterilized.

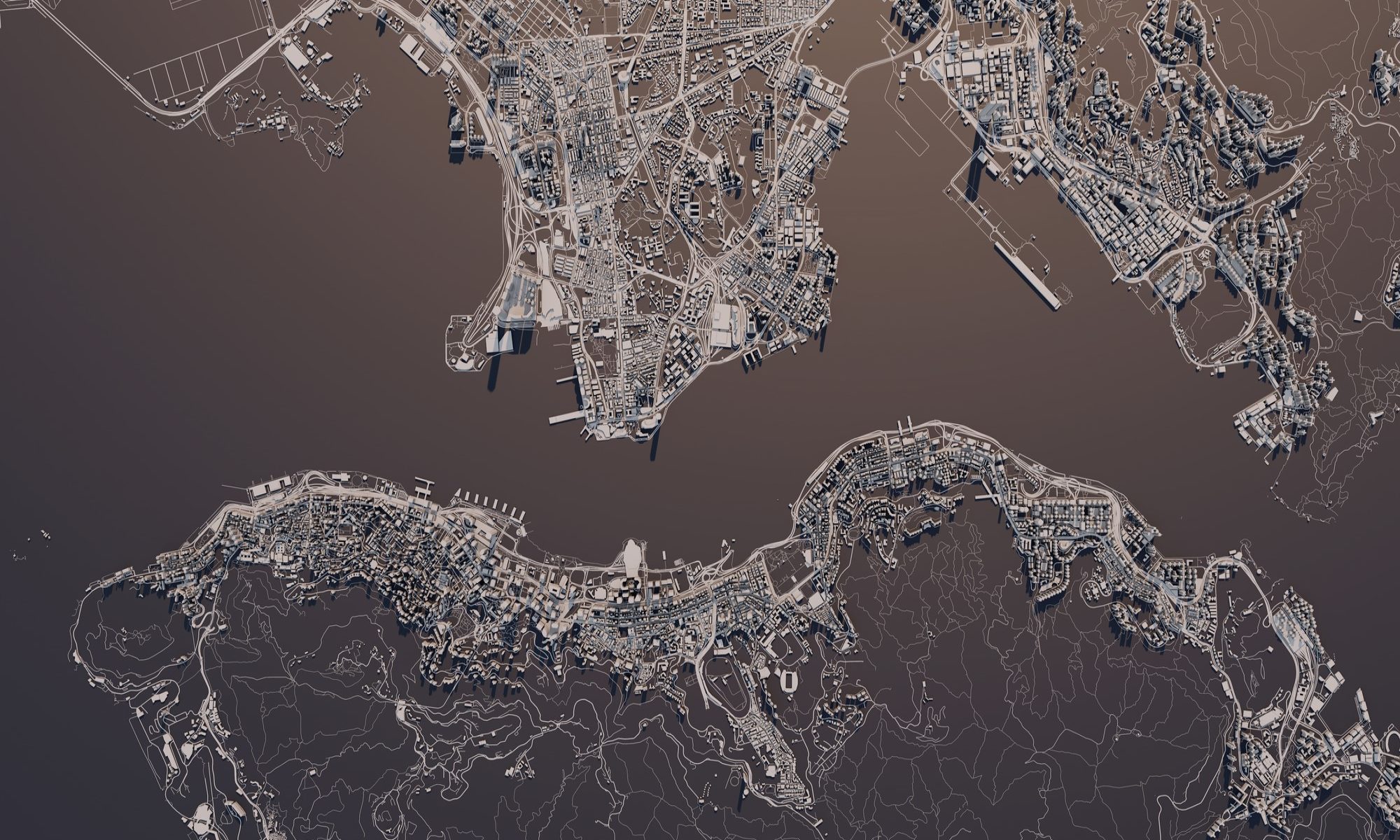

China’s policies in the Xinjian region actually qualify for genocide under two defining acts. The UN Article outlining crimes of genocide that follows just after that cited above states that, “Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group” is a crime of genocide. This highlights further concerns of China’s policies towards Uighurs and also brings the behavior of many governments into question.

As mentioned above, China has been sending ethnic minorities, Uighurs prominent among them, to re-education and work camps. A primary function of these camps includes separating children from there family and community in order to inculcate them in the “Chinese” mode of life. From 2017-2019, thousands of children in the Xinjiang region were separated from their parents in a “systematic campaign of social re-engineering and cultural genocide.” In these schools, children are banned from speaking their Uighur language and are taught instead Chinese mannerisms, customs, and language. As German researcher Dr. Adrian Zenz shares with The Independent, “China has implemented the “weaponisation of education and social care systems” in order to cut off minority children from their roots. “Boarding schools provide the ideal context for a sustained cultural re-engineering of minority societies.”

Again, China is not alone in these tactics. Into the 20th and 21st century, the United States has performed similar operations.

- The United States has relocated children away from their parents multiple times throughout its history as a way of preserving its deluded sense of national identity. From 1860 to 1978, the boarding schools for Indigenous Americans had the express purpose to separate children from their families and cultures and indoctrinate them in the government’s ideas of American-ness. Thousands of children.

- In the last decades, the United States has performed family separation and detention operations at the southern border in the name of National Security but with barely concealed xenophobia and racism. From November 2017 to April 2018, The New York Times reported that the United States had already removed an estimated 700 children from their families at the southern border. Genocide Watch reports, “According to Trump administration statistics, 2,342 children were separated from their families as a result of criminal prosecution between May 5 and June 9, 2018, bringing the total number of children forcibly separated from their families to over 3,000, though no reliable figure is easily available. These children are now scattered across the United States in a confusing mixture of detention facilities and foster home arrangements.”

Retaining control of the family and reproduction as the means of preserving the cultural or ethnic identity of a community is critical. When young members of the community are separated and immersed in another community entirely, their original community is robbed of members, and that individual loses those deep connections. When new members can no longer continue the existence of the community across generations, the interference succeeds at eliminating these communities’ very existence.

In morally assessing the sterilization practices of China on the oppressed Uighur population, it is important to have the appropriate tools to articulate the specific injustice of these policies. That is the goal of the UN declaration, which identifies and underscores the seriousness of actions like forced sterilization.

But what relevant moral weight is added by labeling such actions ‘genocide’ as opposed to merely ‘assault’? When I assault you against your will, moral theorists of any stripe can say “bad!” and explain why it was morally wrong. When we add the context that this assault took away important choices, moral theorists might still be able to account for this being worse than some other harms: because the part of one’s life that involves such choices is important, harming the ability to control it increases the relevant harm. So, perhaps, we could respond “BAD!” to express our moral assessment.

It may become a bit tricky from here. Intuitively, that the harm is being targeted at an individual because of who they are, or because of the group they are a member of, many theories this is not only morally relevant, but that it makes the harm worse. This amplification of wrong is furthered when the harm isn’t just targeting someone based on their identity, but when that targeting is meant to eliminate the person and group’s existence.

But for traditional utilitarians, the oppression or prejudice involved in a harm doesn’t necessarily add to the harm experienced by the individual. Harms will differ for the utilitarian in degree if 1) more individuals are harmed, or 2) the harm is worse, either straightforwardly like a scratch versus a stab, or in a manner similar to that articulated above where perhaps a physical assault might begin to approximate an anesthetized tubal ligation, but the latter comes with more life import.

This has been one of the core critiques of utilitarianism by feminist philosophers. As long as an action produces more harm than good, it is morally permissible. We could imagine a world where prejudice, bigotry, and oppression of some minority communities results in an overall benefit to the population as a whole (just so long as the detractions occur within minority communities). In its simplest form, utilitarianism seems to lack the moral structure to make sense of how this is an unjust and immoral state of affairs. Imagine, for instance, that a library excludes some from entering (women, or non-white people, etc.). Helpful classmates may provide all the copies of the material you need, and therefore no harm is ever accrued by the policy, yet there exists morally wrong behavior and actions. The wrongness of the exclusionary policy isn’t just the harm to those excluded, but lies within the structure of the policy itself — a feature that utilitarianism can struggle to account for.

What this means is that not all moral theories will agree that the charge of genocide possesses some unique moral weight. In order to make China’s policy of forced sterilization as poignantly impermissible to utilitarians, for instance, one need only show that the harms of the policies outweigh the benefits — this does not seem a tall order.

Indeed, for the host of international wrongs listed above, it cannot escape any moral theory that grave wrongs are being committed. According to the United Nations, a major body that passes for international standards of crime and responsibility, countless lives are being abused in ways that cannot be tolerated regardless of the language we use.