This article has a set of discussion questions tailored for classroom use. Click here to download them. To see a full list of articles with discussion questions and other resources, visit our “Educational Resources” page.

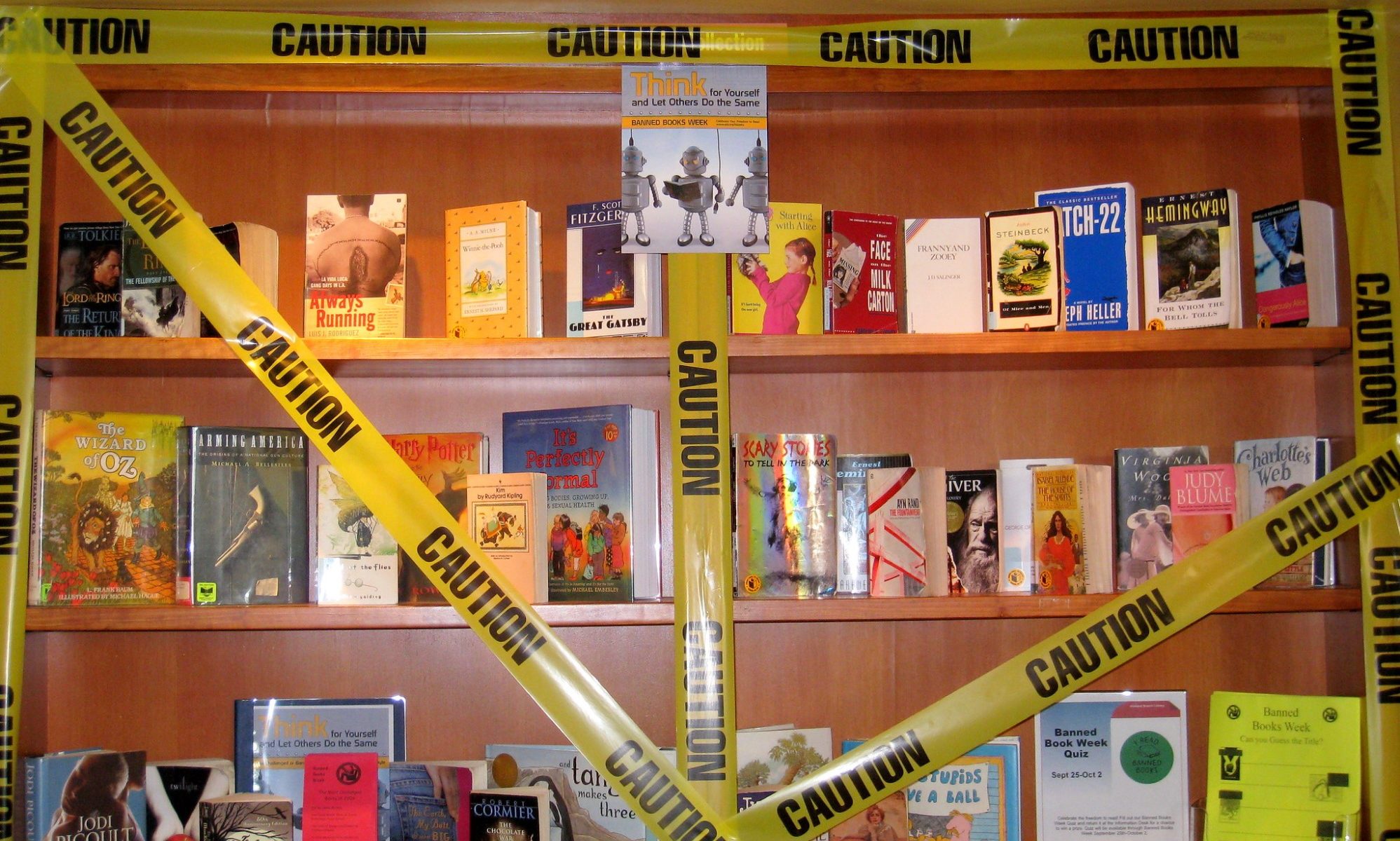

Throughout the summer, armed Idaho citizens showed up at library board meetings at a small library in Bonners Ferry to demand that a list of 400 books be taken off of the shelves. The books in question were not, in fact, books that this particular library carried. In response to the ongoing threats against the library, its insurance company declined to continue to cover them, citing increased risk of violence or harm that might take place in the building. The director of the library, Kimber Glidden, resigned her position in response to the situation, citing personal threats and angry armed protestors showing up at her private home demanding that she remove the “pornography” from the shelves of her library.

This behavior is far from limited to the state of Idaho. In Oklahoma, Summer Boismier, an English teacher at Norman High School was put on leave because she told her students about UnBanned — a program out of the Brooklyn Country Library which allows people from anywhere in the country to access e-book versions of books that have been banned. The program was designed to fight back against censorship and to advocate for the “rights of teens nationwide to read what they like, discover themselves, and form their own opinions.” Boismier was put on leave after a parent protested that she had violated state law HB1775 which, among other things, prohibits the teaching of books or other material that might make one race feel that they are worse than another race. Despite the egalitarian sounding language, the legislation was passed in part to defend a conception of a mythic past and to prevent students from reading about the ways in which the United States’ history of racism continues to have significant consequences to this day. Boismier resigned in protest.

Many states have passed laws banning books with certain content, and that content often involves race, feminism, sexual orientation, and gender identity. And prosecutors in states like Wyoming have considered bringing criminal charges against librarians who continue to carry books that their legislatures have outlawed.

Laws like these capitalize on in-group/out-group dynamics and xenophobia, often putting marginalized groups at further risk of violence, anxiety, depression, and suicide.

In heated board meetings across the country, there appear to be at least two sides to this issue. First, there are the parents and community members who are opposed to censorship or who believe that noise over “pornographic” literature targeting children in libraries is tilting at windmills; in other words, the content the protestors are concerned about simply doesn’t exist. On the other side of the debate, there are parents who are concerned that their children are being exposed to material that is developmentally inappropriate and might actually significantly harm them.

Granting that some of these books contain material that genuinely concerns parents, it simply doesn’t follow that the material to which they object really is bad for the children involved.

The fact that a person is a parent does not make that person an expert on what is best for developing minds and parents do not own the minds of their children.

For instance, one of the most commonly challenged books in the country is The Hate U Give, which is, in part, a book about a teenage girl’s response to the racially motivated killing of her friend by a police officer. Some want this book banned because they don’t want their children internalizing anti-police sentiment. However, reading this kind of a book might increase a child’s critical thinking skills when it comes to how they perceive authority, while also contributing to compassion for historically marginalized groups.

Consider also perhaps the most controversial books — books that have some sexual content.

These books may not be appropriate for children under a certain age, but reading stories in which teenagers are going through common teenage struggles and experiences has the potential to help young readers understand that their thoughts and experiences are totally normal and even healthy.

Parents who want this content banned might be wrong about what is best for their children. Some of these parents might instead be trying to control their children. In any case, the fact that some parents don’t want their children to have access to a particular book does not mean that all young people should be prohibited from reading the books in question. Some parents don’t believe in censorship and trust their children to be discerning and reflective when they read.

That said, the apparent two-sidedness of this debate may well be illusory. After all, there is a simple way to determine whether the library carries books with the kind of content that parents are concerned about — simply check the database. The librarians in question claim that the books about which these parents are complaining are not books that the library carries. What’s more, these “debates” – though sometimes well-intentioned – are more troubling than they may initially appear. More and more people across the country appear to be succumbing to the kind of conspiratorial thinking that tills fertile ground for fascism. These are trends that are reminiscent of moral panics over comic books in the ’50s and ’60s and video games in the ’80s and ’90s.

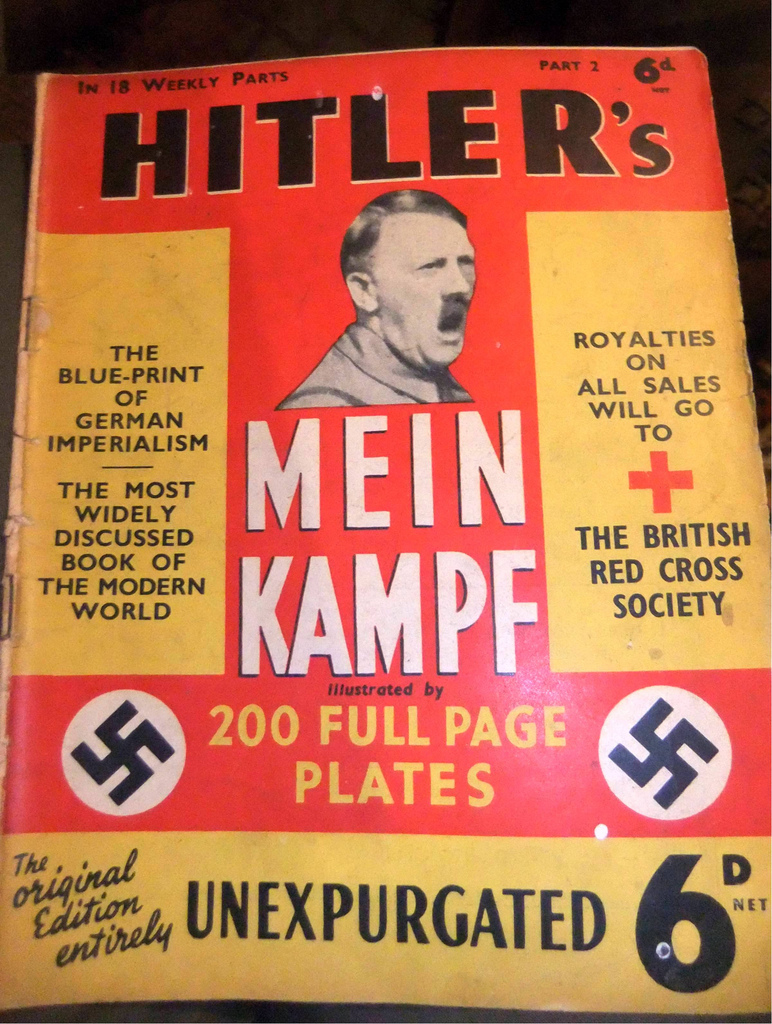

Perhaps the most pressing question confronting our culture today is not whether libraries should continue to carry pornographic or racist materials (since they don’t) but, instead, what we should do about the looming threat of fascism.

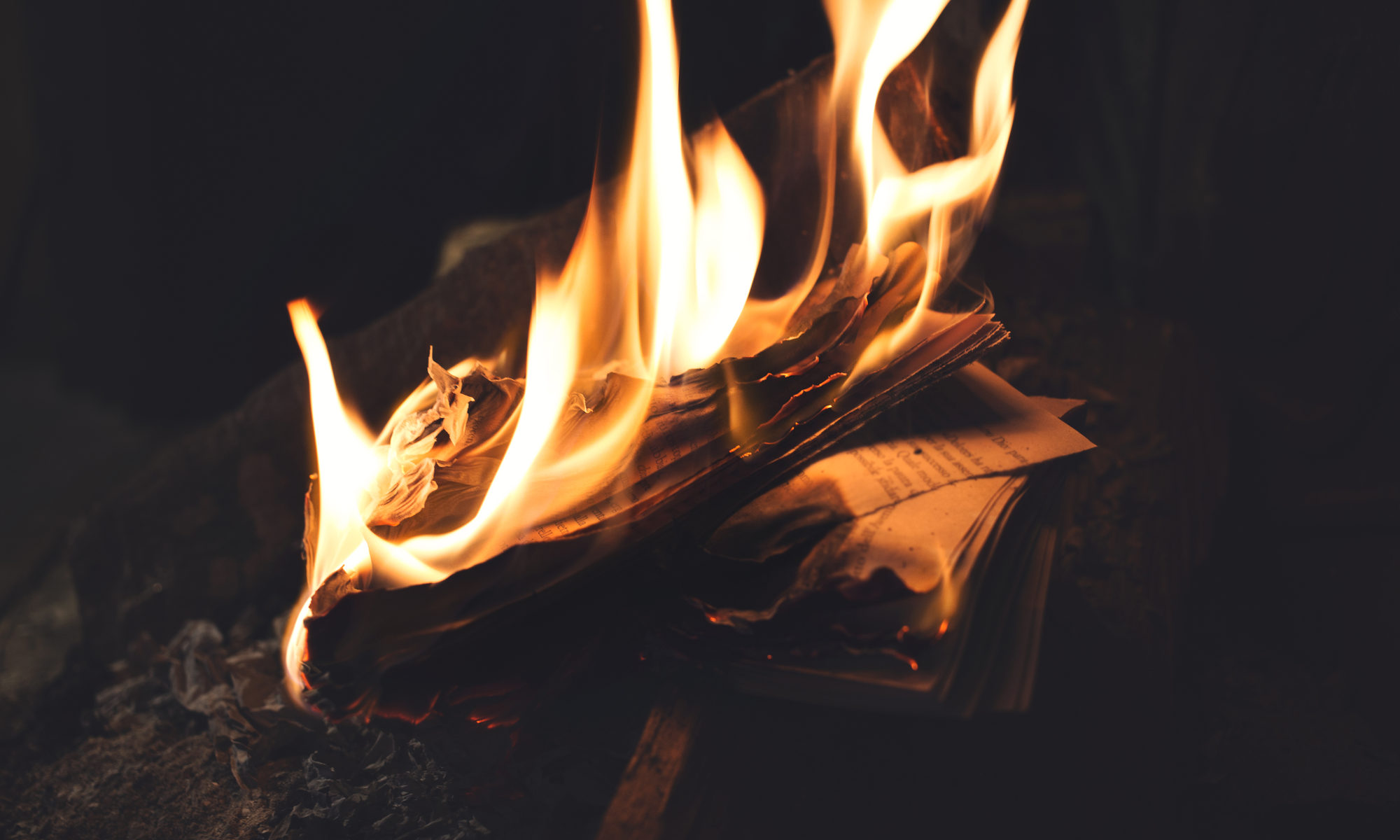

Philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote about her concern that fascist demagogues, who behave as if facts themselves are up for debate, destroy the social fabric of reason on which we all rely. This creates communities of “people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction…and the distinction between true and false…no longer exist.” Novelists have explored these themes countless times, and the restriction of reading material is a common theme in dystopian novels. In particular, readers see these themes explored in 1984, Fahrenheit 451, and The Handmaid’s Tale. In 1984, Orwell describes a “Ministry of Truth” that is responsible for changing history books so that they say all and only what the authoritarian regime wants them to say. In Fahrenheit 451, Bradberry describes an authoritarian regime that disallows reading altogether. In The Handmaid’s Tale, reading is permitted, but only by the powerful, and in this case the only powerful community members are men.

All of these dystopian tales emphasize the importance of language, writing, reading, and freedom of expression both for healthy societies and for healthy individuals.

Ironically, all three of these books are frequently found on banned or challenged books lists.

Rising aggression on the part of those who call for the banning of books has motivated some to respond in purposeful but peaceful ways. In Idaho, for instance, a small group of a couple of dozen concerned citizens – composed of both liberals and conservatives – met in a grove of apple trees to hold a read-in in support of public libraries and against censorship.

These approaches respond to violence with non-violence, an activist approach favored by Martin Luther King Jr. That said, King was also explicit about the fact that the movement he facilitated was a movement of non-violent direct action, which meant more than simply showing up and being peaceful. The strategies King employed involved disrupting society, but non-violently. The Montgomery Bus Boycott, for instance, involved refusing to contribute to the economy of the city by paying for bus fare until it gave up its policy of forcing Black riders to give up their seats to white passengers and to sit at the back of the bus. The non-violent protests in Birmingham in 1963 were intended to affect the profits of merchants in the area so that there would be palpable motivation to end segregation. Non-violent direct action was never intended to be “polite” in the sense that it didn’t provide reasons for frustration. In his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” King says

My citing the creation of tension as part of the work of the nonviolent resister may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word “tension.” I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth.

So, while there is certainly nothing wrong with reading a book under an apple tree, if people want to roll back the wave of censorship and anti-intellectualism – both trends that are part and parcel with fascism – action that is more than “polite” but less than violent may be warranted.