Back in 2014, I remember coming across the Buzzfeed quiz “How Privileged are You?” and answering each question, line by line, to see what my privilege score would be. I remember feeling uncomfortable about the quiz then, but only now do I have the tools to articulate why.

It wasn’t that I was relatively privileged with a well-to-do upbringing and white skin. It wasn’t even necessarily the oppression Olympics, though I did at the time wonder how I compared to others.

The problem was that a numerical score that adds up different experiences doesn’t actually track how privilege and oppression work.

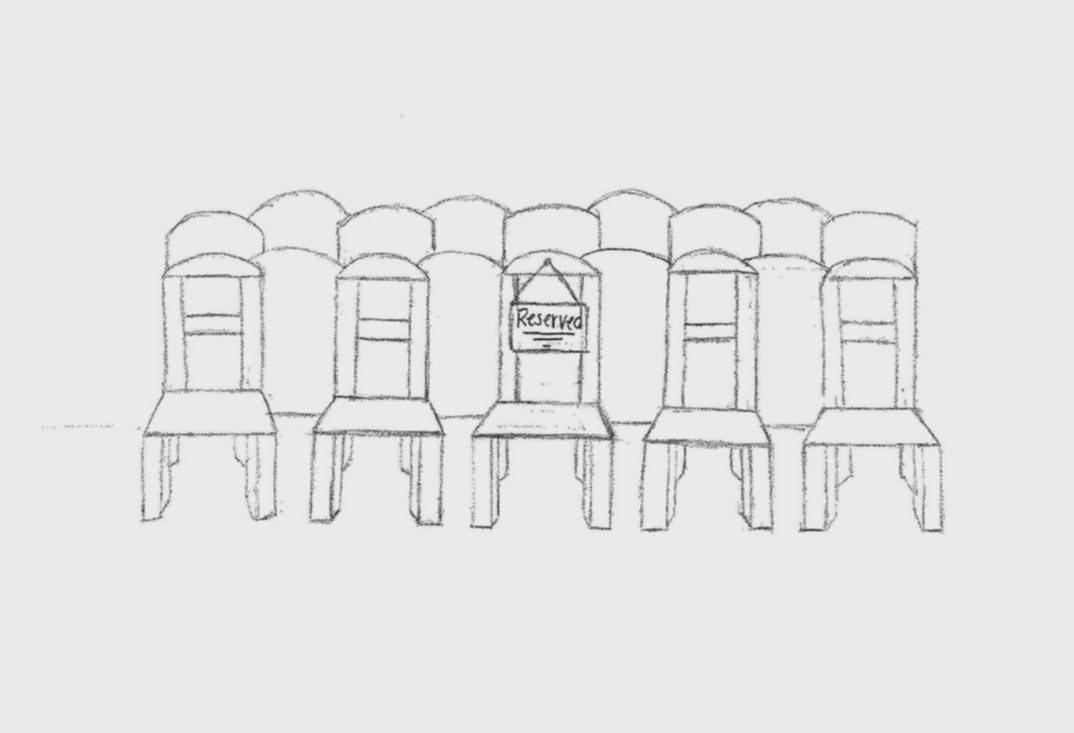

Unfortunately, these kinds of numerical privilege tests have stuck around and periodically re-circulate when conversations about privilege re-enter mainstream discussion. You may have also encountered or participated in a privilege walk, which asks participants to stand in a line and take a step forward or backward in response to each statement instead of tallying a numerical score – those who move to the back are less privileged; those who move forward are more privileged.

What kinds of statements are included on these tests?

- “I am white.”

- “A stranger has never asked to touch my hair, or asked if it is real.”

- “I never had to ‘come out.’”

- “I have never been denied an opportunity because of my gender.”

- “I don’t have any student loans.”

- “My parents are still married.”

- “I have never been shamed for my body type.”

There are a number of other statements that target different identities and experiences. Most fall into broad categories like white experiences, class-relative experiences, Black experiences, trans experiences, non-Christian experiences, etc. These are all good experiences to be aware of.

But privilege doesn’t function in this piecemeal, additive way. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s term intersectionality points out that, for example, Black women’s oppression isn’t the combination of the oppression of Black men and the oppression of white women. Black women are a distinct social class with distinct experiences.

The combination of different axes of oppression is not reducible to the sum of its parts.

Our social categories that shape how we view and treat ourselves and others tend to be more specific than we sometimes think. We respond very differently to an attractive white trans woman than to a fat brown Hispanic trans man. Both are trans; both have very different experiences.

A second issue is that some of the items on these tests seem to relate to how well your life has gone rather than how much your life has been impacted by structural inequalities. Take the statement “my parents are still married.” While divorce is more common in some social groups than others due to structural features, it is not uncommon for highly privileged people to have divorced parents.

If we want to preserve the political function of privilege, it needs to remain a concept that tracks experiences with various structural advantages or disadvantages. The immensely privileged can still have terrible lives through bad luck. Those who lack privilege can live quite good lives as well.

Structural inequalities and interpersonal bigotry can and do make life harder in specific ways for marginalized people, and privilege (or lack thereof) does influence how your life goes for you. But lacking privilege is not the same as having a life full of hardship.

A third issue is that it’s unclear what to do with your score. People often compare themselves with others along axes of privilege in ways that are unhelpful. Sometimes this is done in self-aggrandizing and misleading ways to gain clout on social media (though most often, privileged users will bandy about the one marginalized person that agrees with them just to win a debate). Perhaps more often, people who score as more privileged might feel as if their problems don’t matter or don’t matter as much as those who score as less privileged. Sometimes this is right – when the problems are relatively trivial – but other times this isn’t true.

While we will need to make triage decisions at the level of which political projects to take up and which features of structural oppression are most pressing, comparison at the level of individuals can cause a number of problems. Trauma is still valid even if someone else has it worse.

An aggregate number also does not provide any actionable political guidance.

Scoring individualizes privilege instead of looking at the underlying social structures.

It can promote a kind of navel-gazing about our own experiences instead of group conversations about the problems that specifically affect us and what we can do about them. The way out of oppressive structures is not by finding the most marginalized person and placing the burden of liberation on them; it’s by working together.

Fourth, when we have conversations about privilege, there are a number of reactions that the privileged have when their relative structural advantage is pointed out: “Why are you trying to make me feel guilty?” “My life hasn’t been easy.” “I’ve experienced [insert unrelated hardship], so I know what oppression is like.” “But we’ve overcome [insert kind of oppression].” “I’ve never heard of that, so it can’t be real.” “The real problem is [insert unrelated issue].” “Well, [other marginalized group] also oppresses [marginalized group under discussion], so any oppression I participate in shouldn’t be called out.”

These various kinds of denial, outrage, and misdirection are often used by the privileged to recenter themselves in conversations. That tendency will not be affected by the kind of icebreaker you use to talk about privilege, whether it be the Buzzfeed quiz or a privilege walk.

However, some of these responses are (willful or otherwise) misunderstandings of what privilege is. It’s not personal virtue. It’s not how your life has gone on the whole. It’s a particular set of experiences that arise when people in well-specified social groups interact with social and structural advantages or disadvantages.

Privilege tests can sometimes feed into these misconceptions about privilege by obscuring intersectionality, making it sound as if privilege = how well your life has gone, and encouraging unhelpful comparisons. For these and other reasons, some people have already moved away from the privilege quiz/privilege walk model.

I don’t think that getting rid of privilege tests will solve the problems we have in discussing oppression. But we don’t need to aggravate these problems with a teaching resource that could be easily replaced with better materials. Conversations about privilege will always be hard, because people who are privileged do not directly experience what it’s like to live under structural oppression, and people who are oppressed often internalize oppressive narratives.

I hope that we can all replace these petty blame games and denials of privilege with solidarity and community. The fight isn’t between the privileged and the marginalized; it’s between the people who support systems of oppression and the people who want to dismantle them.

If you’re privileged, use that privilege to help.