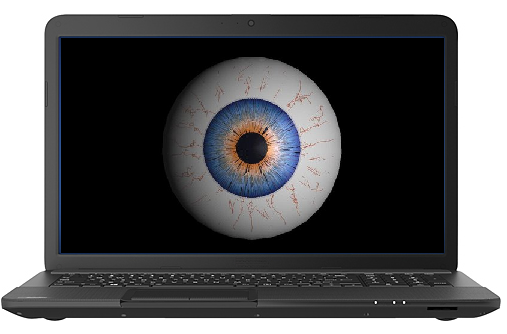

If you find yourself traveling, you may notice that your identity is being verified in a new and different way. Instead of showing your ID to an employee in the security line, you may find that you’re asked to insert it into a machine while a camera captures your image. The machine software will then determine whether that image matches the person on your ID. Some airports use databases for identification so that the ID does not even need to be scanned.

The technology has been developed by the transportation security administration, and they’ve been quietly rolling it out at airports across the country. The primary advantages are that this system is potentially faster, easier, and more accurate. Airline travel in the middle of the 20th century was advertised as glamorous and comfortable. There now seems to be no end to the inconveniences travelers have to endure. To some, anything that makes the process less like an interrogation would count as an improvement.

On the other hand, many are alarmed to see this technology emerge without much warning. Some are concerned about the government having access to this kind of data. They are now allegedly using it to make airline travel easier, but there are lingering suspicions about what it could be used for in the future. It has become commonplace for people to become aware that a corporation has used their data for purposes to which they did not knowingly consent; data is sold to third parties and used for targeted advertising. For many, these concerns are even more troubling when the entity gathering the information is the government. The government could potentially build a database of everyone’s faces and use it in settings in which citizens would not be comfortable. For instance, while smart buildings offer significant potential for more environmentally friendly institutions, some are also designed with facial recognition technology. Some argue that this would be an improvement — the technology could recognize potential threats or disgruntled former employees before acts of violence can take place. Others respond that this benefit would not be worth the violation of privacy that would result — the government could potentially know where people are all the time, at least when they are in or near government buildings. If the moral right to privacy involves maintaining control over one’s own body, that right seems to be substantially violated when corporations and the government are cyberstalking people all of the time.

There are also serious concerns about how these systems will determine which individuals count as threats. People are concerned about what’s become familiar forms of algorithm bias. There is data to support the idea that facial recognition programs do less well identifying the faces of people of color. A recent study concluded that Native American, Black, and Asian people were 100% more likely to be misidentified than their white counterparts, and women were much more likely to be misidentified than men. (Middle-aged men had the highest accuracy rate of identification overall.) People of color already encounter racial profiling at airports, and this policy has the potential to make these problems worse. Our current political circumstances make discrimination even more likely. Heated political rhetoric has made life more challenging for Muslims and Chinese people, especially at airports. Further, concerns about being misidentified by AI airport security may create a chilling effect on travel for members of these groups, constituting a form of systemic racial oppression.

Those who defend the system point out that travelers can opt out of facial recognition by simply saying, “Please don’t take my photo.” If this is the case, the argument is that the government isn’t really violating people’s autonomy — they have the right to say “no.” There are, however, a number of responses to this argument. First, travelers may be concerned about what might happen to them if they refuse to comply. Travel is a critical human need, especially as our experience is increasingly globalized and our loved ones and livelihoods are more likely to be scattered across states, countries, and even continents. If a person is detained by security, they might miss the birth of a child or saying goodbye to a dying relative. The circumstances at airports are inherently coercive and people might be deeply concerned that they won’t get to their location unless they go along. Second, a person may have a right to say “no” as a matter of policy, but it is very unlikely that any particular passenger will know that they have it. Finally, a person is unlikely to want to make waves, delay other travelers, and potentially embarrass themselves. If a “right of refusal” policy is coercive and lacks transparency, citizens cannot give fully free and informed consent.

Like so many recent developments in technology, facial recognition motivates questions about authority and political legitimacy. Who gets to make these decisions and why? The answers to these questions are far from obvious. Allowing those who stand to gain the most power or earn the greatest profit to dictate protocols seems like a bad idea. Instead, we may have to trust our elected representatives to craft policy. The problem with this approach is that, for many legislators, winning re-election takes precedence over any policy issue, no matter how dire. We need look no further than lack of progress on climate policy to see that this is the case. Alternatively, we could bring questions of the greatest existential import to public referendum and decide them by a direct democratic process. The problem with this is the standard problem for democracy posed by philosophers for decades — the population as a whole can be woefully underinformed and act tyrannically.

One lesson that we’re left with is that we shouldn’t let these major changes blow by without comment or criticism. It’s easy to adopt a kind of cynicism that causes us to believe in technological determinism — the view that any development that can happen will happen. But policies are made by people. And one of the most important roles that sound public philosophy can play is to demand justification and ensure that policy is supported by deliberate and defensible moral principles.