This article contains spoilers for the Disney+ series Moon Knight.

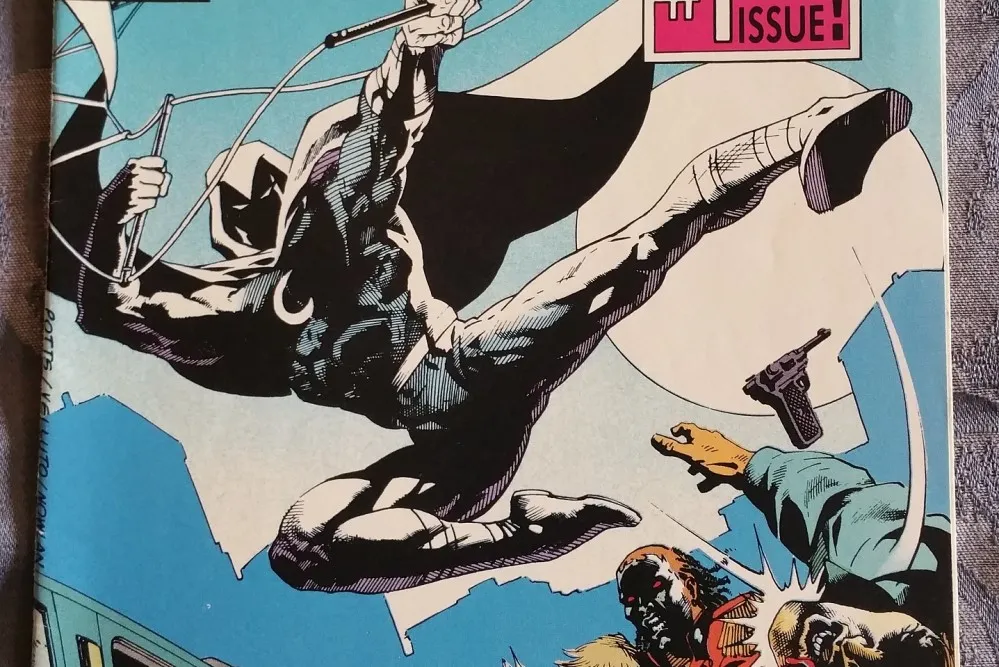

In Disney’s Moon Knight, two Egyptian Gods advocate for two very different models of justice. Their avatars, of whom the titular character is one, are the humans tasked with doing the Gods’ bidding. Konshu is the beaked God of vengeance who manipulates his avatars to punish wrongdoers. His form of justice depends on the concept of desert — people should be punished for the choices that they make after, and only after, they have made them. Throughout the series, the main antagonist, Harrow (who was, himself, once Konshu’s avatar) attempts to release the banished alligator God Ammit. Ammit has the power to see into the future; she knows the bad actions that people will perform and instructs her avatars to punish these future wrongdoers preemptively, before anyone is harmed by the bad decisions.

As is so often the case with Marvel villains, the mission shared by Harrow and Ammit is complicated.

The struggle involved between the two Gods is not a battle between good and evil (neither of them fit cleanly into either of those categories). Instead, it is a conflict between competing ideologies. Ammit and Harrow want to bring about a better world. The best possible world, they argue, is a world in which the free will of humans is never allowed to actually culminate in the kinds of actions that cause pain and suffering. If people were prevented from committing murders, starting wars, and perpetrating hate, there would be no victims. The reasoning here is grounded in consequences; the kinds of experiences that people have in their lives are ultimately what matters. If we can minimize the kinds of really bad experiences that are caused by other people, we should.

Nevertheless, viewers are encouraged to think of Konshu’s vision of justice as superior; Mark and Steven spend six episodes trying to prevent Harrowing from reviving Ammit. The virtue of Konshu’s conception of justice is that it takes the value of the exercise of free will seriously. The concept of reward is inextricably linked to the concept of praise and the concept of blame is similarly linked to the concept of punishment. People are only deserving of praise and blame when they act freely; free will is a necessary condition for praise or blame to be apt. A person is only praiseworthy for an action if they freely choose to perform it, and the same is true with blame. Ammit’s form of justice doesn’t respect this connection, and the conclusion the viewer is invited to draw is that the God therefore misses something central about what it is that fundamentally justifies punishment.

The suggestion is that retributivism — the view that those who have chosen to do bad things should “get what they deserve” — is the theory of punishment that we should adopt in light of the extent to which it emphasizes the importance of free will.

But it isn’t that simple, in the MCU or in the real world. Later episodes of the series explore the theme of mitigating circumstances, and the viewer is left to wonder: are all circumstances mitigating? In episode 5, Marc and Steven travel to an afterlife and, at the same time, through their own memories. As viewers have likely suspected, Marc has dissociative identity disorder, and Steven is a personality he created to protect him from the abuse that he suffered at the hands of his mother. In childhood, Marc and his little brother Randall went to play in a cave together and rising waters resulted in Randall’s drowning. Marc’s mother never stops blaming him for the death and takes it out on him until the day that she dies. It is clear that Marc has carried a significant sense of guilt along with him all of his life. Steven assures him, “it wasn’t your fault, you were just a child!”

The actions that young Marc took might appear to be chosen freely; he went to the cave with his brother despite the fact that he knew doing so was dangerous. Yet it does seem that Steven is correct to suggest that the inexperience of youth undermines full moral responsibility. The same is true with at least some forms of mental illness. If the trauma of Marc’s past has fractured his psyche, is he really responsible for anything that he does, either as Marc or as Steven?

The kinds of factors that contribute to who a person becomes are largely outside of their control.

No one can choose their genetics, where they are born, who their parents are, the social conditions and norms that govern who it is deemed “acceptable” for them to be, whether they are raised in conditions of economic uncertainty, and so on.

Many factors of who we are end up being largely a matter, not of free will, but of luck. If this is the case, it is far from clear that, as viewers, we should be cheering for Konshu’s model of justice to win in the end. Anger and resentment are common sentiments in response to wrongdoing, but retributive attitudes about justice often create barriers to experiencing emotions that are even more important — forgiveness, compassion and empathy. Existence on the planet is not one giant battle between good and evil; explanations for behavior are considerably messier and more complicated.

Moon Knight’s story has only just begun, and the philosophical themes promise to be rich. With any luck, they’ll motivate us to think more critically about justice in the real world. Even if we could see into the future, there are good arguments against pursuing Ammit’s strategy — it seems unfair to punish someone to prevent them from doing something wrong (the metaphysics of time are kind of sketchy there, too). Konshu’s strategy — a heavily retributivist strategy — closely resembles the one we actually follow in the United States; we incarcerate more people than any country in the world. Our commitment to giving wrongdoers “what they deserve” may stand in the way of more nuanced moral thought.