Detroit had automobiles, Pittsburgh had steel, and Boston had textiles. Amongst these former capitals of industrialization in the United States is one that is seldom mentioned: the coal kingdom of Hazard, Kentucky. Hazard started booming as a coal town in 1912 when a railway along the North Fork of the Kentucky River was built with a station there. Soon thereafter, nearby coal mines started opening frequently, making for an abundance of jobs and a rapidly growing population. Between 1920 and 1930, the population of Hazard grew from 4,348 to over 7,000. The small city still hosts a Black Gold Festival every September to celebrate its industrial roots.

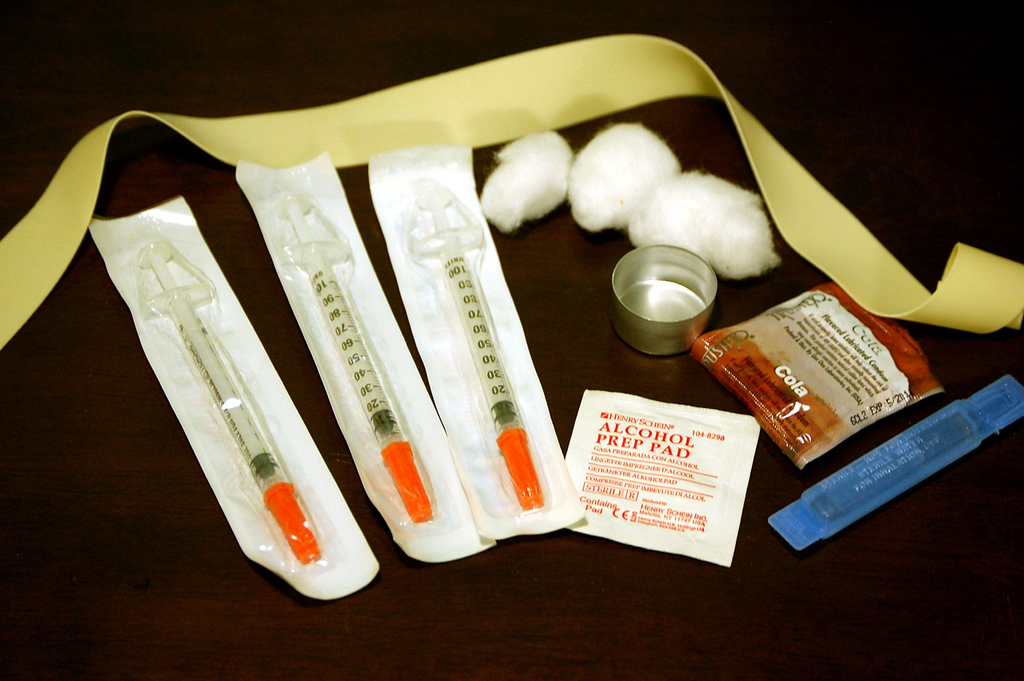

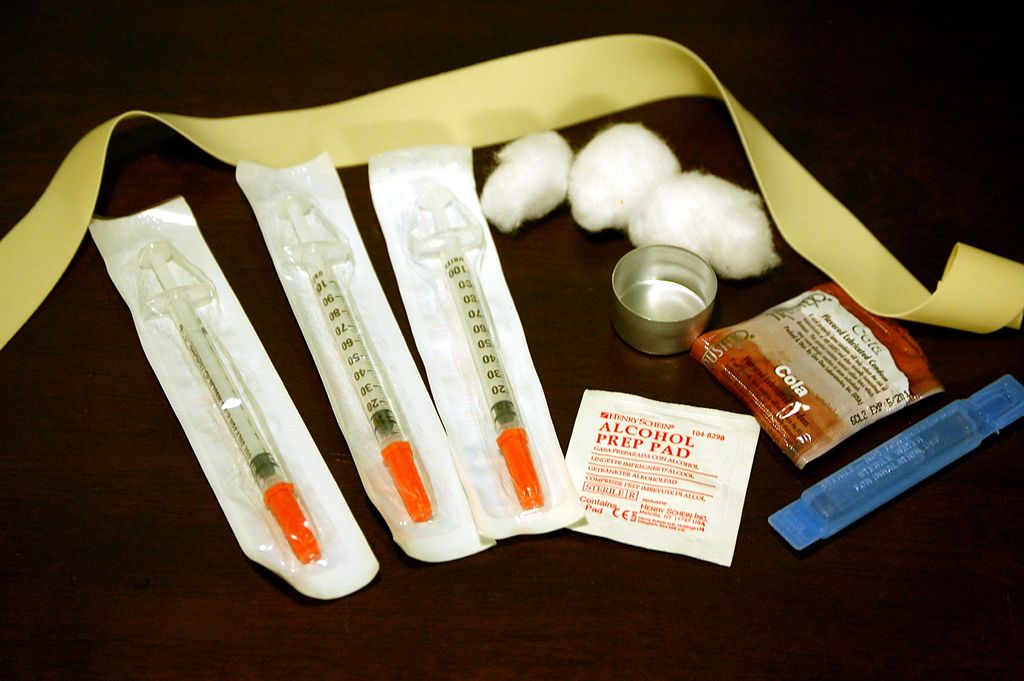

However, Hazard’s once rich history has now turned into severe poverty, unemployment, and addiction. The population is currently 5,600—shrinking over 1,800 since its peak in 1940 despite heavy national population growth. Additionally, Hazard’s median household income of $20,690 is almost $40,000 under the U.S. median, with about 31% of its small population living below the poverty line. Perhaps the darkest aspect of Hazard’s downturn is the opioid addiction crisis. Perry County, Kentucky (where Hazard is located) had the most opioid-related hospitalizations in the nation in 2017, with 6% of the county’s population having been hospitalized due to opioid abuse. Three counties surrounding Perry were also in the top ten in the nation.

Hazard, however, is not isolated in the challenges it faces. Towns all over Appalachia have experienced severe downturn characterized by these same issues. To illustrate, six of the 15 states with the highest opioid death rates are Appalachian states (West Virginia is first with 43.4 out of every 100,000 people dying of opioid overdose, followed by Ohio at third, Maryland at fourth, Kentucky at 10th, Pennsylvania at 12th, and Tennessee at 14th). Between the years 1999 and 2016, the number of opioid-related deaths in Pennsylvania jumped 736 percent, while those in Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia jumped over 1,000 percent. These rates are compared to a national increase of 528 percent. With the opioid epidemic, Appalachian states also deal with unusually high poverty and crumbling infrastructure that has led to the contamination of drinking water.

Why is it that these challenges are so inflated in Appalachia? Why is a region of the U.S. that once prospered and was overflowing with opportunities for lucrative employment is now rapidly decaying? The most obvious reason is the decline in demand for coal. U.S. coal consumption peaked as recently as 2007 but has dropped 44 percent since then, reaching its lowest level in almost 40 years. This number is expected to drop another eight percent this year. Additionally, of the 1,470 coal-fired generators in the U.S. in 2007, 540 have been retired as of September 2018. The decrease in demand has inevitably resulted in a decrease in coal production, and therefore a decrease in coal jobs. Coal mining jobs in the U.S. have dropped a whopping 71 percent since 1985. This effect is more pronounced in Appalachia. Coal production in Appalachia fell 45 percent from 2005 to 2015, resulting in a loss of about 33,500 mining jobs since 2011. In Hazard in particular, the local coal industry now produces approximately 4.1 million tons of coal annually, dropping about 13 million tons since 2008, and losing about 13,000 coal jobs in eastern Kentucky since 2011. This year marks the lowest number of coal jobs Kentucky has had since 1898.

People across the nation have noticed Appalachia’s suffering, and have searched for causes behind it. Donald Trump in particular ran on a platform that included the revival of the Appalachian coal industry. He puts most of the blame for its recent lack of success on environmental regulations imposed by Democratic politicians. In one tweet referring to the Obama administration’s regulations on carbon emissions, Trump wrote, “Obama’s coal regulations will destroy the coal industry, put Americans out of work, raise electricity prices, and lead to blackouts.” Trump continues to tweet into his presidency about how he has “ended the war on coal.” The coal town of Hazard seems to agree, as 77.2 percent of voters in Perry County, Kentucky voted for Trump in 2016. However, Trump’s assumption that environmental regulations are destroying the coal industry and, by association, the economy of Appalachia, is overly simplistic. In fact, environmental regulations only account for approximately 3.5 percent of the total decline in U.S. coal production. The reality is that the coal industry is dying primarily of natural causes.

There are two main reasons behind the Appalachian coal industry’s decline: decreasing productivity, and competition with other energy sources. The former is caused by the dwindling supply of easily-accessible coal deposits in the Appalachian Mountains. After almost a century and a half of mining, miners now have to dig deeper into the mountains for usable coal. To offset this increased difficulty in mining, coal corporations have turned towards mechanization, which puts even more miners out of work. Even with a mechanized workforce, however, Appalachian coal cannot keep up with coal production in western states such as Wyoming, Montana, and Texas, where deposits are closer to the surface and therefore require less time and money to mine.

Along with challenges the coal industry faces to keep up production, it must also deal with higher competition with other sources of energy, namely renewable energy (wind power, solar power, etc.) and natural gas. Renewable energy is beginning to compete with coal because of rising concern amongst Americans about the environment. Burning coal is one of most harmful sources of electricity in terms of carbon emissions, and while it is cheap, Americans are beginning to prioritize environmental harms caused by energy sources over the economic costs they incur. This gives renewable energy sources (which are typically more expensive) an advantage over coal. Most competitive with the coal industry, however, is natural gas. In 2016, natural gas surpassed coal as the U.S.’s leading source of electricity. This is largely due to falling natural gas prices after the fracking boom of the late 2000’s. Natural gas is also cheaper to produce than coal, and burning natural gas puts out significantly less carbon emissions than coal.

Because the Appalachian coal industry is already becoming obsolete at the hands of struggling productivity and a more competitive energy market, it would be foolish and reckless for politicians to attempt breathing life back into it. Rather, these efforts should be put into diversifying Appalachia’s economy. Some coal towns are already beginning to do this. The residents of Hinton, West Virginia, for example, have started the Appalachian Beekeeping Collective, a nonprofit aimed at training out-of-work coal miners in beekeeping. This nonprofit has grown to operate in 17 counties throughout the state of West Virginia in just two years since its creation, and helps ex-miners earn money in a more sustainable field of work. Additionally, the state of Pennsylvania, which has traditionally been a coal state and is still one of the biggest energy producers in the U.S., is moving its economy to subsist on nuclear power and natural gas while coal is on the decline. Even Hazard is turning the site of one of its former surface mines into the USA Drone Port—a research and testing facility for drone companies to use. To supplement this, the Hazard Community and Technical College has introduced courses in unmanned technology, drone flight, photography, and videography: all skills that will translate well into USA Drone Port’s workforce. The Technical College has already graduated 200 students in these fields, many of whom used to be coal miners.

Unfortunately, the coal industry does not appear to be a significant part of the future U.S. economy. However, adapting to the future is possible, and many places around Appalachia are showing it. Appalachia is a region full of innovation, grit, and most importantly, people who are ready to work for the betterment of their communities, with or without coal.