Last month, I discussed some of the moral questions raised by Astrobotic Technology’s recent (and, ultimately, failed) attempt to land a probe containing human (and dog) remains on the moon. I focused on the cultural significance of the moon – particularly for the Navajo Nation, who protested the lander prior to launch. While there is an understandable allure to having one’s remains deposited on a celestial body, I expressed doubts that the interests of the dead (if such things even exist) are sufficient to outweigh the cultural harms caused by such practices.

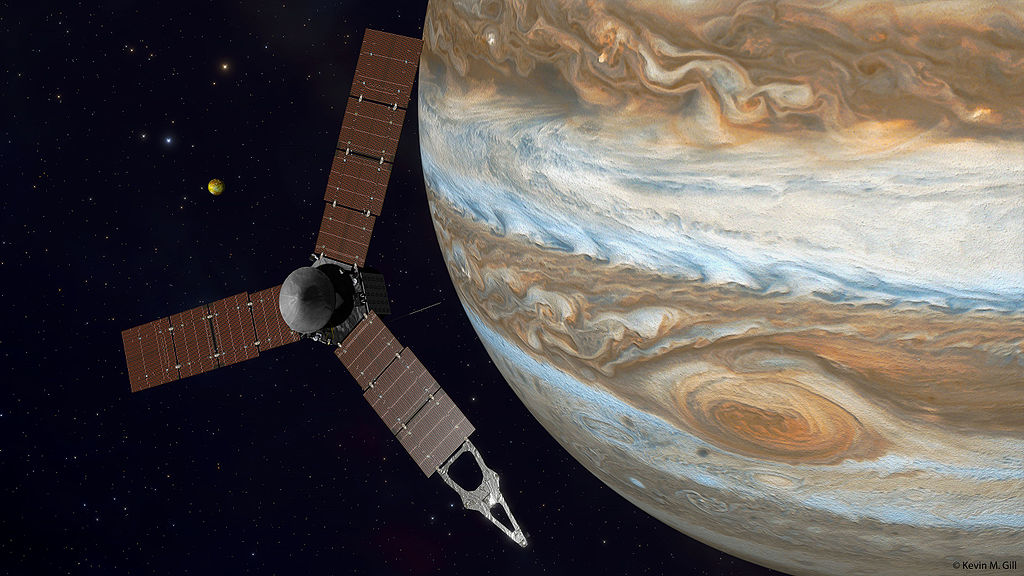

But the potential concerns don’t stop there. The Peregrine lander raises a number of other ethical problems – the first and foremost of which is how we are to appropriately deal with property in space. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 held that no part of space can be subject to appropriation by a particular state. And while this merely establishes a legal (not moral) norm, it seems to support the more general idea of space as a sort of global commons. Like the oceans and the atmosphere, it’s there for the enjoyment of all. But does this enjoyment have its limits? Certainly. There are ways in which we can enjoy a commons that might limit the ability of others to enjoy it in that same way. While we might fish from a common lake, overfishing will deplete that resource so that others are unable to do so. This is the oft-cited “tragedy of the commons.”

Our use of the commons therefore requires restrictions. This is precisely what John Locke sets out to address in his theory of property. An important part of his theory describes the process by which we are able to take common property and make it our own. How? By mixing our labor with it. Thus, when I trudge into a common forest, fell a tree, and craft that timber into a birdhouse, I come to own that birdhouse. The same is true when I pick an apple or fish up a trout. But, according to Locke, there is one proviso: that in helping ourselves to the commons, we must leave enough – and as good – for others. Put another way, when dealing with the commons, we must limit our actions so that anyone who comes after us can deal with the commons in precisely the same way. Thus, if I take so much timber (or apples, or fish) that others are unable to take the same amount, I have used the commons in a way that is impermissible.

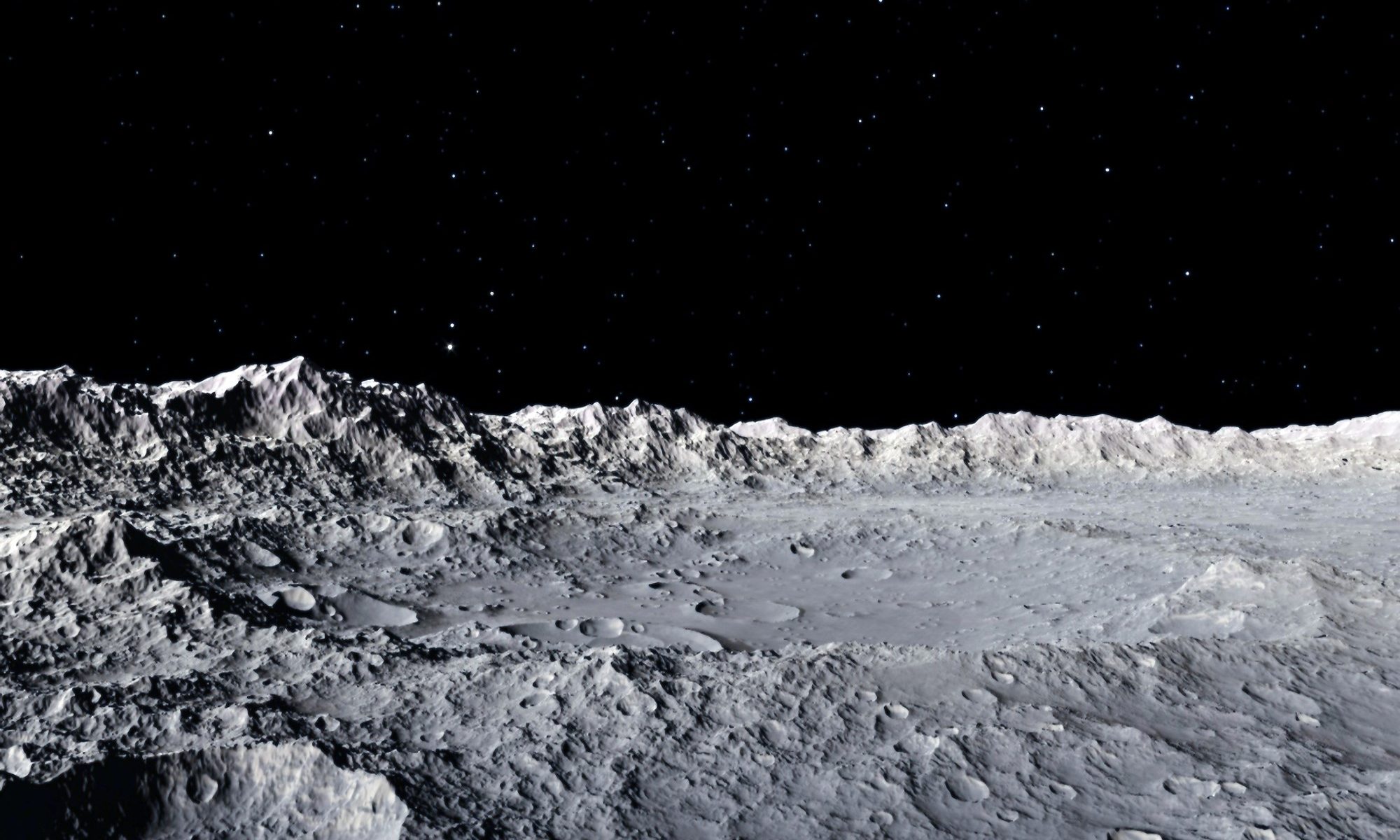

It’s an intuitive notion, and one that captures the more general sense in which we believe that people shouldn’t take more than their “fair share.” But how does it apply to the actions of Astrobotic Technologies? Well, the “Lockean proviso” doesn’t apply merely to taking things from the commons, but also to leaving them there. Again, it helps describe a common intuition that we shouldn’t use the commons for the excessive dumping of litter or toxic waste. Consider, then, the mission of the Peregrine lander. The Moon might be global commons – there for the enjoyment of all. But it is also finite. The deposition of human remains there utilizes – and potentially spoils – a portion of that commons, however small. In doing so, it leaves less for others to enjoy, thus potentially violating the Lockean proviso.

But there’s room for disagreement with this idea. While finite, the Moon is still pretty big. Perhaps it’s true that we can deposit our remains there while still leaving enough space (no pun intended) for everyone else to do likewise. Perhaps every last person on the planet could make the Moon their final resting place, without removing the ability of others to do likewise.

But this is where things get tricky. It’s easy to think of commons – and how they are to be shared – purely in terms of those of us who currently exist. But commons are more complicated than this. Typically, they are temporally extended – they exist from generation to generation. This means that we’re not simply required to leave as much and as good for everyone else currently able to enjoy the commons – but also for all of those who will come to enjoy those same commons in the future. This is why we might consider it unfair to fell and mill an entire forest and split the proceeds equally among the current generation of a community. While every member of that community might’ve received their “fair share,” they’ve acted in a way that deprives future generations from enjoying that same resource.

This is the concern of intergenerational justice – and it features predominantly in many discussions of environmental ethics. Whether it be creating an inhospitably warm climate, eradicating a species, or befouling water and soil with harmful pollutants, there are all sorts of actions that prevent future generations from the proper use and enjoyment of the commons. And something similar might be happening here with the Moon. We must be careful that our use now of the Moon doesn’t prevent our descendants from enjoying this global common in the future. If we litter our nearest celestial body with human and animal remains (or all other manner of waste, space debris, and – as was proposed at one point – nuclear fallout) we might risk doing precisely this.