The following piece discusses the series Severance. I avoid specific plot details. But if you want to go into the show blind, stop reading now.

Severance follows a group of employees at Lumon Industries, a biotech company of unspecified purpose. The main characters have all received a surgery before starting this job. Referred to as the “severance” procedure, this surgery causes a split in the patient’s personality. After surgery, patients awaken to find that while they have factual memories, they have no autobiographical memories – one character cannot remember her name or the color of her mother’s eyes but remembers that Delaware is a state.

However, the severance procedure does not cause irreversible amnesia. Rather, it creates two distinct aspects of one’s personality. One, called the outie, is the individual who was hired by Lumon and agreed to the procedure. However, when she goes to work, the outie loses consciousness and another aspect, the innie, awakens. The innie has no shared memories with the outie. She comes to awareness at the start of each shift, the last thing she remembers being walking to the exit the previous day. Her life is an uninterrupted sequence of days at the office and nothing else.

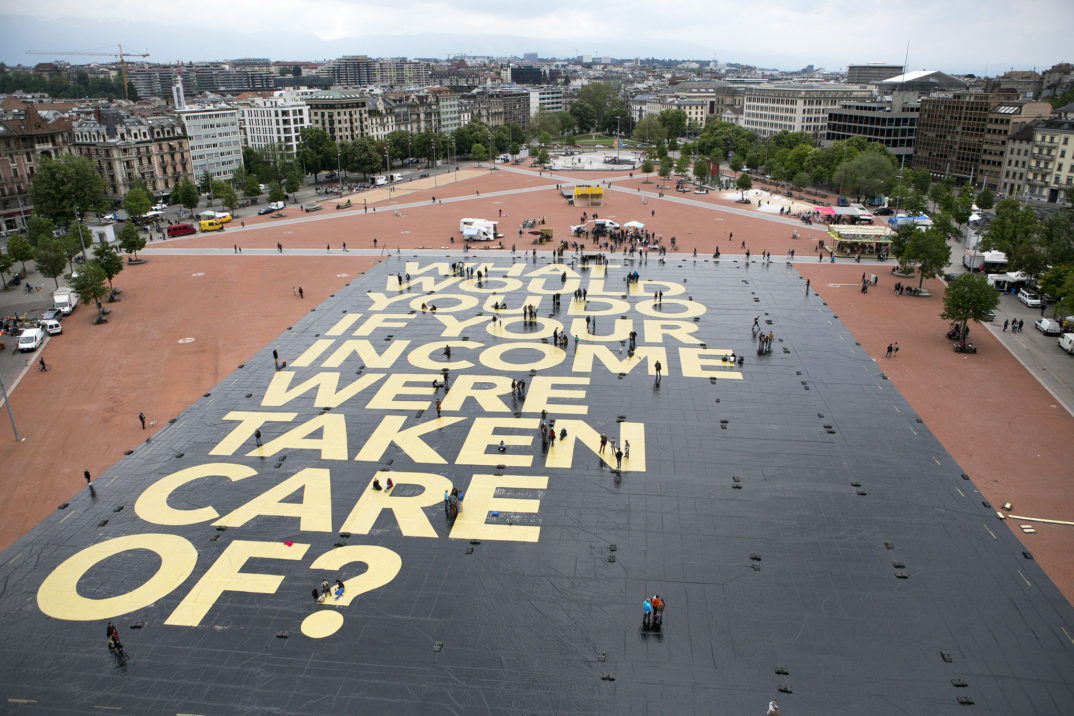

Before analyzing the severance procedure closer, let us take a few moments to consider some trends about work. As of 2017, 2.6 million people in the U.S. worked on-call, stopping and starting at a moment’s notice. Our smartphones leave us constantly vulnerable to emails or phone calls that pull us out of our personal lives. The pandemic and the corresponding need for remote, at-home work only accelerated the blurring of lines between our personal lives and spaces, and our work lives. For instance, as workplaces have gone digital, people have begun creating “Zoom corners.” Although seemingly innocuous, practices like these involve ceding control of some of our personal space to be more appealing to our employers and co-workers.

Concerns like these lead Elizabeth Anderson to argue in Private Government that workplaces have become governments. Corporate policies control our behavior when on the clock and our personal activities, which can be easily tracked online, may be subject to the scrutiny of our employers. Unlike with public, democratic institutions where we can shape policy by voting, a vast majority have no say in how their workplace is run. Hence this control is totalitarian. Further, “low skilled” and low-wage workers – because they are deemed more replaceable – are even more subject to their employer’s whims. This increased vulnerability to corporate governance carries with it many negative consequences, on top of those already associated with low income.

Some consequences may be due to a phenomenon Karl Marx called alienation. When working you give yourself up to others. You are told what to produce and how to produce it. You hand control of yourself over to someone or something else. Further, what you do while on the clock significantly affects what you want to do for leisure; even if you loved gardening, surely you would do something else to relax if your job was landscaping. When our work increasingly bleeds into our personal lives, our lives cease to be our own.

So, we can see why the severance procedure would have appeal. It promises us more than just balance between work and life, it makes it impossible for work to interfere with your personal life; your boss cannot email you with questions about your work on the weekend and you cannot be asked to take a project home if you literally have no recollection of your time in the office. To ensure that you will always leave your work at the door may sound like a dream to many.

Further, one might argue that the severance procedure is just an exercise of autonomy. The person agreeing to work at Lumon agrees to get the procedure done and we should not interfere with this choice. At best, it’s like wearing a uniform or following a code of conduct; it’s just a condition of employment which one can reject by quitting. At worst, it’s comparable to our reactions to “elective disability”; we see someone choosing a medical procedure that makes us uncomfortable, but our discomfort does not imply someone should not have the choice. We must not interfere with people’s ability to make choices that only affect themselves, and the severance procedure is such a choice.

Yet the show itself presents the severance procedure as morally dubious. Background TV programs show talking heads debating it, activists known as the “Whole Mind Collective” are campaigning to outlaw severance, and when others learn that the main character, Mark, is severed, they are visibly uncomfortable and uncertain what to say. So, what is the argument against it?

To explain what is objectionable about the severance procedure, we need to consider what makes us who we are. This is an issue referred to in philosophy as “personal identity.” In some sense, the innie and the outie are two parts of the same whole. No new person is born because of the surgery and the two exist within the same human organism; they share the same body and the same brain.

However, it is not immediately obvious that people are simply organisms. A common view is that a significant portion, if not all, of our identity deals with psychological factors like our memories. To demonstrate this, consider a case that Derek Parfit presented in Reasons and Persons. He refers to this case as the Psychological Spectrum. It goes roughly as follows:

Imagine that a nefarious surgeon installed a microchip on my brain. This microchip is connected to several buttons. As the surgeon presses each button, a portion of my memories change to Napoleon Bonaparte’s memories. When the surgeon pushes the last button, I would all of and only Napoleon’s memories.

What can we say about this case? It seems that, after the doctor presses the last button Nick no longer exists. It’s unclear when I stopped existing – after a few buttons, there seems to be a kind of weird Nick-Napoleon hybrid, who gradually goes full Napoleon. Nonetheless, even though Nick the organism survives, Nick the person does not.

And this allows us to see the full scope of the objection to the severance procedure. The choice is not just self-regarding. When one gets severed, they are arguably creating a new person. A person whose life is spent utterly alienated. The innie spends her days performing the tasks demanded of her by management. Her entire life is her work. And what’s more troubling is that this is the only way she can exist – any attempts to leave will merely result in the outie taking over, having no idea what happened at work.

This reveals the true horror of what Severance presents to us. The protagonists have an escape from increasing corporate protrusion into their personal lives. But this release comes at a price. They must wholly sacrifice a third of their lives. For eight hours a day, they no longer exist. And in that time, a different person lives a life under the thumb of a totalitarian government she has no bargaining power against.

The world of Severance is one without a good move for the worker. She is personally subject to private government which threatens to consume her whole life, or she severs her work and personal selves. Either way, her employer wins.