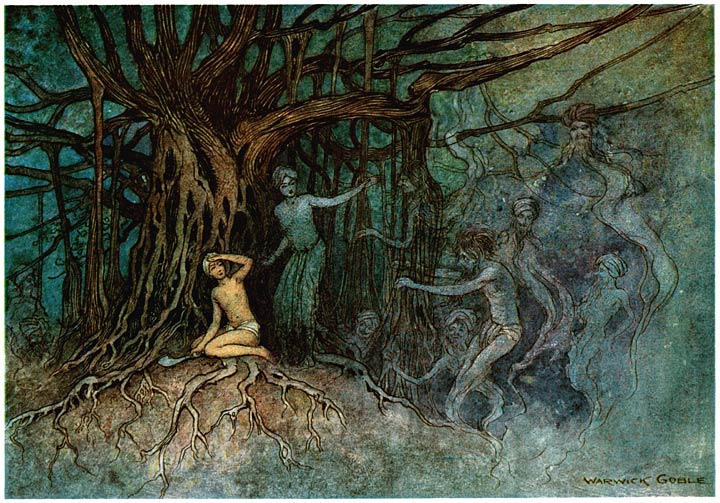

On September 2nd, Wizards of the Coast, the company that produces official Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) materials, apologized for offensive content in its lore concerning the Hadozee race released in the most recent Spelljammer: Adventures in Space boxed set. The Hadozee are a monkey-like humanoid race known for their sailing abilities and love of exploring. They have been included in the Spelljammer series since 1990, but recent updates to the lore, as well as some of the Hadozee artwork, prompted criticism that the Hadozee evoked anti-Black stereotypes.

The updates restructured the Hadozee’s origins, stating that the race was created after a wizard captured wild Hadozee and gave them an experimental elixir that made them intelligent, more human-like in appearance, and, as a byproduct, more resilient when harmed. The wizard’s plan was to sell the enhanced Hadozee as slaves for military use; however, the wizard’s apprentices helped the Hadozee escape with the rest of the elixir. The Hadozee returned to their homelands to use the rest of the elixir on other wild Hadozee.

As reddit user u/Rexli178 explained, the main issues players had with this lore were that “the Hadozee were enslaved and through their enslavement were transformed from animals to thinking feeling people,” and that “the Hadozee had no agency in their own liberation.” This, coupled with the fact that anti-Black stereotypes often compare Black people to monkeys, plus the well-known historical racist sentiment that enslavement was necessary for the improvement of the Black race, plus the idea that Black people don’t feel as much pain when harmed, plus Hadozee artwork that seemed to evoke the imagery of minstrel shows, plus the fact that the Hadozee were characterized in other places as happy servants of the Elves all came together to paint a picture that many players found damning.

It is worth noting that the critique of the Hadozee lore was not that the Hadozee reminded players of Black people. The critique was that the Hadozee echo anti-Black stereotypes and narratives that have been used to oppress Black people.

Stating that something is similar to a stereotype of a group is not the same as stating that that thing is similar to the group itself; this is especially clear when the stereotype in question is plainly false and dehumanizing.

The recent Hadozee controversy is not the only misstep Wizards of the Coast has made in the past few years — the 2016 adventure Curse of Strahd contained a people called the Vistani who evoked negative stereotypes associated with the Roma people. At the same time, Wizards of the Coast is slowly trying to change how race functions in D&D, removing alignment traits (good vs. evil, chaotic vs. lawful) and other passages of lore text to allow for greater freedom when constructing a character.

What went wrong with the Hadozee storytelling?

Whether the parallels with real life oppression and negative stereotypes were intentional, it seems clear that this lore pulled players out of the fantasy world and recreated negative tropes associated with anti-Black racism.

How strongly it pulled on those tropes might be a matter for debate; however, I think the more interesting philosophical question here is: How should D&D include stories of oppression into their game materials, if at all? The answer to this question will likely depend upon particular histories of oppression and the details of how a given narrative of oppression is woven in the story, but I think we can say a few things to answer the general version of the question.

The first observation to make is that D&D is a fantasy series. When playing, we want to be able to escape our mundane world and experience the excitement of casting spells, fighting monsters, and just joking around with our friends. Because D&D is a fantasy series, it seems that the stories about oppression that the game facilitates should be sufficiently removed from actual histories of oppression. Even more so it seems that they should avoid reifying oppressive stereotypes in worldbuilding.

Some historical themes can be pulled upon, but WotC should be careful not to let too many of those themes overlap.

If a story maps too closely onto the experiences of oppressed groups that still exist and are still oppressed in some ways, D&D has left the realm of fantasy, doing a disservice to its storytelling and potential for healthy escapism.

And, if a story maps too closely onto oppressive stereotypes that have been used to denigrate certain groups of people historically, that can also set off alarm bells.

It is worth noting, too, that just because a piece of lore does not bring certain players out of the game – because they do not see the parallels to real-life oppressive tropes or narratives – that alone does not mean the lore is passable. The point here is for players of all different backgrounds, including from different marginalized groups, to be able to suspend disbelief and enjoy the fantasy world of D&D. Storytelling that makes it difficult for members of certain marginalized groups to equally enjoy and participate in the game is unjust and can practically exclude people from the game.

Now, this isn’t to say that Dungeon Masters (DMs, or the person who runs the D&D game) should not be allowed to modify or reinvent D&D materials to tell stories that more closely map onto real-life instances of oppression. Some members of oppressed groups might appreciate being able to navigate oppressive frameworks in a world in which they have power and can become heroes. Whether these homebrew stories are exclusionary is another tricky question.

The point is, while players should have the freedom to adapt and change stories, the basic blueprint put out through official D&D materials should be maximally inclusive.

This brings me to my second point — Dungeons & Dragons should not shy away from storytelling that allows players to explore oppressive societies, complex social issues, and other uncomfortable situations that they may face in their real lives. The trick is that the players need to be able to make their own choices about how they want to engage in these issues. And, if the storytelling is sufficiently removed from real-life histories of oppression, that will make it a safer space for players to explore how their characters might respond in those scenarios. In order to include these elements and tell these stories well, it would be good for Wizards of the Coast to hire writers who are familiar with common oppressive tropes and narratives and who could redirect problematic stories in a different direction.

It’s interesting to note that the people who have reacted against the Hadozee controversy and claimed that the Spelljammer material was just fine seem to agree with these two principles. One common reaction appears to be something like “fantasy is different than reality, and we shouldn’t confuse the two.” While the bulk of those reactions insinuate that people are seeing connections between Black stereotypes and the Hadozee that aren’t there, I think that they are roughly in line with the idea that fantasy is something that is distinct from reality and should be kept that way. I take it that those who are critiquing the Hadozee lore are critiquing it for this same reason.

Another common reaction seems to be along the lines of “we shouldn’t get rid of conflict and difficult themes just to make some politically correct folks happy,” which lines up with the idea that D&D should be a space where those scenarios can be explored by all players. I imagine that those who are unhappy with the Hadozee lore would also agree with this principle, so long as players can be active in shaping their characters and experiences and the game does not exclude certain groups of players.

To be inclusive to all D&D players, however, Wizards of the Coast needs to have better representation of people with different life experiences and understandings of the world in their writing rooms. This will not only make for better storytelling, but it will also facilitate gameplay that does not alienate certain players in the room. Let’s hope that Wizards of the Coast as well as the larger D&D community start to head more in that direction.