Consider three things. First: technological development means that there are many more people in the world than there used to be. This means that, if we survive far into the future, the number of future people could be really, really big. Perhaps the overwhelming majority of us have not yet been born.

Second: the future could be really good, or really bad, or a big disappointment. Perhaps our very many descendants will live amazing lives, improved by new technologies, and will ultimately spread throughout the universe. Perhaps they will reengineer nature to end the suffering of wild animals, and do many other impressive things we cannot even imagine now. That would be really good. On the other hand, perhaps some horrific totalitarian government will use new technologies to not only take over humanity, but also ensure that it can never be overthrown. Or perhaps humanity will somehow annihilate itself. Or perhaps some moral catastrophe that is hard to imagine at present will play out: perhaps, say, we will create vast numbers of sentient computer programs, but treat them in ways that cause serious suffering. Those would be really bad. Or, again, perhaps something will happen that causes us to permanently stagnate in some way. That would be a big disappointment. All our future potential would be squandered.

Third: we may be living in a time that is uniquely important in determining which future plays out. That is, we may be living in what the philosopher Derek Parfit called the “hinge of history.” Think, for instance, of the possibility that we will annihilate ourselves. That was not possible until very recently. In a few centuries, it may no longer be possible: perhaps by then we will have begun spreading out among the stars, and will have escaped the danger of being wiped out. So maybe technology raised this threat, and technology will ultimately remove it.

But then we are living in the dangerous middle, and what happens in the comparatively near future may determine whether our story ends here, or instead lasts until the end of the universe.

And the same may be true of other possibilities. Developments in artificial intelligence or in biotechnology, say, may make the future go either very well or very poorly, depending on whether we discover how to safely harness them.

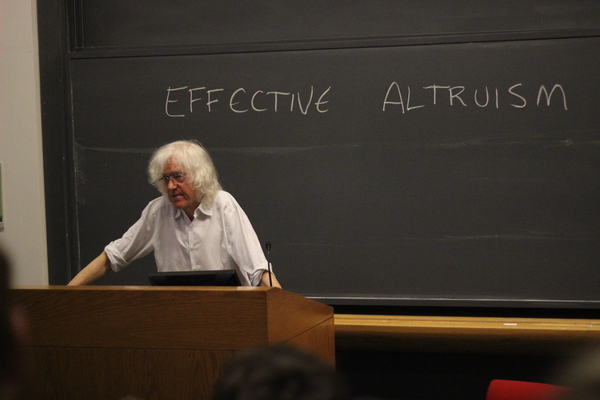

These three propositions, taken together, would seem to imply that how our actions affect the future is extremely morally important. This is a view known as longtermism. The release of a new book on longtermism, What We Owe the Future by Will MacAskill, has resulted in it getting some media coverage.

If we take longtermism seriously, what should we do? It seems that at least some people should work directly on things which increase the chances that the long-term future will be good. For instance, they might work on AI safety or biotech safety, to reduce the chances that these technologies will destroy us and to increase the chances that they will be used in good rather than bad ways. And these people ought to be given some resources to do this. (The organization 80,000 Hours, for example, contains career advice that may be helpful for people looking to do work like this.)

However, there is only so much that can productively be done on these fronts, and some of us do not have the talents to contribute much to them anyway. Accordingly, for many people, the best way to make the long-term future better may be to try to make the world better today.

By spreading good values, building more just societies, and helping people to realize their potential, we may increase the ability of future people to respond appropriately to crises, as well as the probability that they will choose to do so.

To large extent, Peter Singer may be correct in saying that

If we are at the hinge of history, enabling people to escape poverty and get an education is as likely to move things in the right direction as almost anything else we might do; and if we are not at that critical point, it will have been a good thing to do anyway.

This also helps us respond to a common criticism of longtermism, namely, that it might lead to a kind of fanaticism. If the long-term future is so important, it might seem that nothing that happens now matters at all in comparison. Many people would find it troubling if longtermism implies that, say, we should redirect all of our efforts to help the global poor into reducing the chance that a future AI will destroy us, or that terrible atrocities could be justified in the name of making it slightly more likely that we will one day successfully colonize space.

There are real philosophical questions here, including ones related to the nature of our obligations to future generations and our ability to anticipate future outcomes. But if I’m right that in practice, much of what we should do to improve the long-term future aligns with what we should do to improve the world now, our answers to these philosophical questions may not have troubling real-world implications. Indeed, longtermism may well imply that efforts to help the world today are more important than we realized, since they may help, not only people today, but countless people who do not yet exist.