The U.K. election has been and gone.

It brought a remarkable result, with the Labour Party securing 411 out of 650 seats in the House of Commons (HoC – the parliamentary chamber where the public votes members in). This result meant Labour became the new governing party, and Sir Kier Starmer, its leader, the new Prime Minister. This is up from a paltry 202 in the 2019 election. On the flip side, the Conservative Party lost, and lost badly. It went from being the governing party, with a vote share of 365 in 2019, to going into opposition with a 2024 result of only 121.

It is hard to convey to those outside the U.K. just how seismic this shift is. Labour has secured the largest HoC majority since Tony Blair in 1997, with only four more seats than Starmer achieved.

But it was not just the two biggest parties that had an exciting election night. The Liberal Democrats went from 11 to 72 seats. The Scottish National Party, meanwhile, were decimated, going from 48 to 9 seats. There were also notable results for the Green Party, Sinn Féin, the Democratic Unionist Party, and others, including the new party on the block, Reform UK. It is with this latest that I want to stay.

Now, to say that Reform is a new party is technically accurate. However, more accurately, the party is just the latest iteration in a long line of regenerations centered around a figurehead – Nigel Farage. In 1997, UKIP (United Kingdom Independence Party) came onto the scene. It stuck around for a while, but by the 2019 election, UKIP had become the Brexit party. Then, between 2019 and this year’s election, it had changed again into Reform UK. Farage played a decisive role in each era, although he wasn’t always front and center in the political fray. What matters most for us is that, in 2024, Reform UK, a party leaning very much to the right of the political spectrum, got the third-highest overall vote share of any party. This is despite, due to the quirk of the UK’s first past the post electoral system, only securing five seats in the HoC. Most importantly, though, is the simple fact that Reform has made a big splash on the UK electoral scene under the stewardship of the recently returned Farage.

However, because they are a new party, Reform don’t have the pedigree or (legitimate) financial resources of the likes of Labour or the Conservatives upon which to draw their membership or parliament hopefuls. Thus, their campaign has lacked some of the rigor of the older parties. Farage himself admitted this when offensive comments made by several of his parliamentary hopefuls came to light. In other words, Reform’s campaign has been rougher around the edges, and there has been less control from the center than other parties.

This lack of (at least official) oversight came to a peculiar climax in the past week when suspicion started swirling that Mark Matlock, the reform candidate for Clapham and Brixton Hill, didn’t actually exist.

The short of it is that Matlock’s campaign materials featured an AI-generated portrait. This fact slipped by largely unnoticed until July 8th, when a tweet pointed the fact out. Skepticism was fueled further by the fact that Matlock didn’t appear when the election results were announced in the constituency where he was standing; this is very unusual.

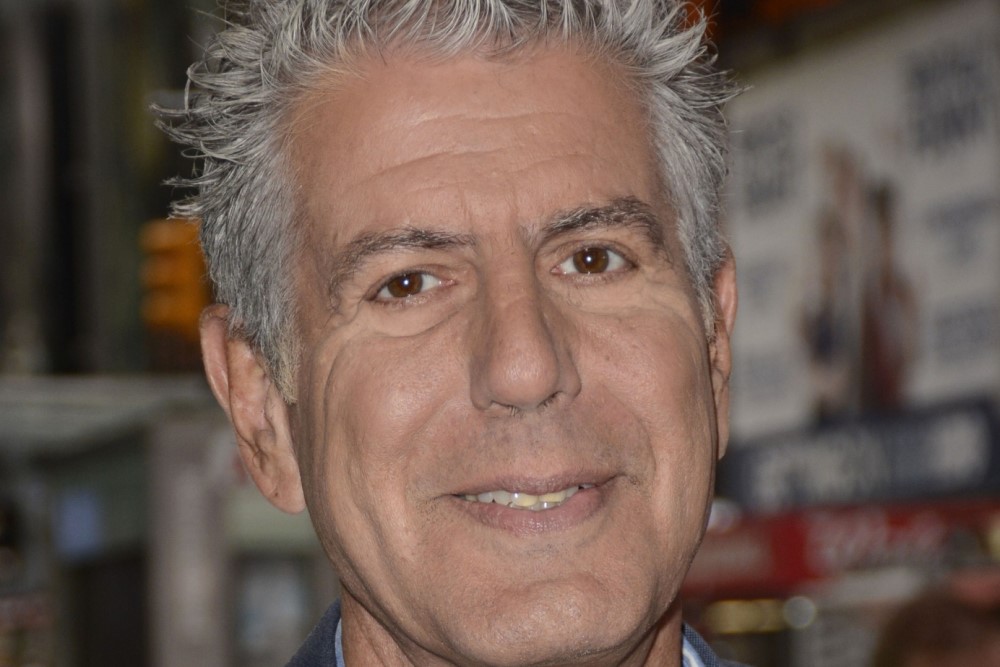

Matlock eventually revealed himself to the world in an interview on GB News. His explanation for using an AI-generated image of himself rather than an actual picture was that he didn’t have a tie in the Reform UK colors. So, he generated one instead. This is not the only notable difference, though. His AI-generated image also makes Matlock look thinner and younger, with smoother skin and a fuller head of hair. In totality, while one might see a resemblance, I think you’d be hard-pressed to say they share a strong likeness.

All this demands we ask what, if anything, is the matter with Matlock using AI in this way. Did he do something wrong?

The impact AI might have on elections and trust in politics has been covered greatly. The U.K. Cabinet Office released guidance intending to disrupt “the impact of disinformation campaigns, which are increasingly being created using generative AI.” And, with the run-up to the U.S. election fully underway, concerns about bad actors using AI to influence voters will only increase.

Yet, it seems self-evident that just because someone uses AI in their campaign, this doesn’t inherently make that use unethical or the campaign itself reprehensible. If all Matlock had done was take an existing picture of himself and used AI to alter the color of his tie to match Reform UK colors, this wouldn’t strike me as particularly offensive. We might think it was odd, given he could have just bought a tie, but that’s a different point.

Indeed, we are all aware of using technology to alter the way reality is portrayed, and many of us participate in it. Filters on digital images, holding cameras at specific angles to accentuate some features and hide others, or simply being tactical in what we capture all drive a wedge between reality and the way it is portrayed. And this isn’t new. Every effort to depict the world through an artistic medium inevitably means that some reality is described with more fidelity than others.

So where is the harm? Where is the wrong? Well, I think it stems from the fact that Matlock didn’t just alter the color of his tie. He tried to portray himself as someone with an entirely different appearance. Someone skinnier, younger, and with more hair. This was not an honest representation of himself, and therein lies the point.

This was an active effort to be dishonest. It was not simply a touch-up but a total fabrication. He changed how he looked, not simply by aligning himself with Reform UK’s color scheme but also by amending his entire appearance.

Now, you might think that this shouldn’t matter. After all, what counts is not how politicians look but how they act and what they do. Whether they are old, bold, fat or thin doesn’t matter. What matters is that they do what is right for their constituents. And I would agree. However, honesty is one of the most important qualities one wants in their leaders – without it, you lose trust, and trust is fundamental. Just look at what brought down the last three Conservative Prime Ministers.

What Matlock did, then, undermined the public’s ability to trust him. After all, if he can’t be honest about how he looks – something fundamental to him as a person and obviously something he can’t hide – then how can we trust him to be honest about something more substantial?

In the end, while concern about AI’s impact might currently focus on those looking to spread disinformation or subvert the electoral process, we shouldn’t overlook the more insipid usage of it to make people look, for lack of a better word, more attractive.