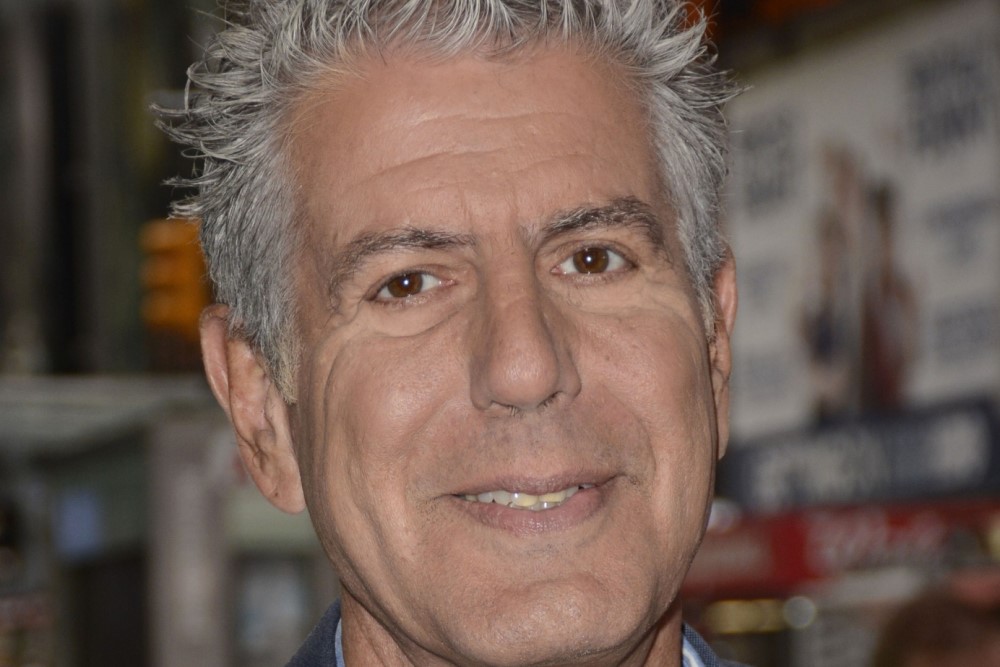

Will the Real Anthony Bourdain Please Stand Up?

Released earlier this month, Roadrunner: A Film About Anthony Bourdain (hereafter referred to as Roadrunner) documents the life of the globetrotting gastronome and author. Rocketing to fame in the 2000’s thanks to his memoir Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly and subsequent appearances on series such as Top Chef and No Reservations, Bourdain was (in)famous for his raw, personable, and darkly funny outlook. Through his remarkable show Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown, the chef did more than introduce viewers to fascinating, delicious, and occasionally stomach-churning meals from around the globe. He used his gastronomic knowledge to connect with others. He reminded viewers of our common humanity through genuine engagement, curiosity, and passion for the people he met and the cultures in which he fully immersed himself. Bourdain tragically died in 2018 while filming Parts Unknown’s twelfth season. Nevertheless, he still garners admiration for his brutal honesty, inquisitiveness regarding the culinary arts, and eagerness to know people, cultures, and himself better.

To craft Roadrunner’s narrative, director Morgan Neville draws from thousands of hours of video and audio footage of Bourdain. As a result, Bourdain’s distinctive accent and stylistic lashings of profanity can be heard throughout the movie as both dialogue and voice-over. It is the latter of these, and precisely three voice-over lines equating to roughly 45-seconds, that are of particular interest. This is because the audio for these three lines is not drawn from pre-existing footage. An AI-generated version of Bourdain’s voice speaks them. In other words, Bourdain never uttered these lines. Instead, he is being mimicked via artificial means.

It’s unclear which three lines these are, although Neville has confirmed one of them, regarding Bourdain’s contemplation on success, appears in the film’s trailer. However, what is clear is that Neville’s use of deepfakes to give Bourdain’s written words life should give us pause for multiple reasons, three of which we’ll touch on here.

Firstly, one cannot escape the feeling of unease regarding the replication and animation of the likeness of individuals who have died, especially when that likeness is so realistic as to be passable. Whether that is using Audrey Hepburn’s image to sell chocolate, generating a hologram of Tupac Shakur to perform onstage, or indeed, having a Bourdain sound-alike read his emails, the idea that we have less control over our likeness, our speech, and actions in death than we did in life feels ghoulish. It’s common to think that the dead should be left in peace, and it could be argued that this use of technology to replicate the deceased’s voice, face, body, or all of the above somehow disturbs that peace in an unseemly and unethical manner.

However, while such a stance may seem intuitive, we don’t often think in these sorts of terms for other artefacts. We typically have no qualms about giving voice to texts written by people who died hundreds or even thousands of years ago. After all, the vast majority of biographies and biographical movies feature dead people. There is very little concern about the representation of those persons on-screen or the page because they are dead. We may have concerns about how they are being represented or whether that representation is faithful (more on these in a bit). But the mere fact that they are no longer with us is typically not a barrier to their likeness being imitated by others.

Thus, while we may feel uneasy about Bourdain’s voice being a synthetic replication, it is not clear why we should have such a feeling merely because he’s deceased. Does his passing really alter the ethics of AI-facilitated vocal recreation, or are we simply injecting our squeamishness about death into a discussion where it doesn’t belong?

Secondly, even if we find no issue with the representation of the dead through AI-assisted means, we may have concerns about the honesty of such work. Or, to put it another way, the potential for deepfake facilitated deception.

The problem of computer-generated images and their impact on social and political systems are well known. However, the use of deepfake techniques in Roadrunner represents something much more personable. The film does not attempt to destabilize governments or promote conspiracy theories. Rather, it tries to tell a story about a unique individual in their voice. But, how this is achieved feels underhanded.

Neville doesn’t make it clear in the film which parts of the audio are genuine or deepfaked. As a result, our faith in the trustworthiness of the entire project is potentially undermined – if the audio’s authenticity is uncertain, can we be safe in assuming the rest of the film is trustworthy?

Indeed, the fact that this technique had been used to create the audio footage was concealed, or at least obfuscated, until Neville was challenged about it during an interview reinforces such skepticism. That’s not to say that the rest of the film must be called into doubt. However, the nature of the product, especially as it is a documentary, requires a contract between the viewer and the filmmaker built upon honesty. We expect, rightly or wrongly, for documentaries to be faithful representations of those things they’re documenting, and there’s a question of whether an AI-generated version of Bourdain’s voice is faithful or not.

Thirdly, even if we accept that the recreation of the voices of the dead is acceptable, and even if we accept that a lack of clarity about when vocal recreations are being used isn’t an issue, we may still want to ask whether what’s being conveyed is an accurate representation of Bourdain’s views and personality. In essence, would Bourdain have said these things in this way?

You may think this isn’t a particular issue for Roadrunner as the AI-generated voice-over isn’t speaking sentences written by Neville. It speaks text which Bourdain himself wrote. For example, the line regarding success featured in the film’s trailer was taken from emails written by Bourdain. Thus, you may think that this isn’t too much of an issue because Neville simply gives a voice to Bourdain’s unspoken words.

However, to take such a stance overlooks how much information – how much meaning – is derivable not from the specific words we use but how we say them. We may have the words Bourdain wrote on the page, but we have no idea how he would have delivered them. The AI algorithm in Roadrunner may be passable, and the technology will likely continue to develop to the point where distinguishing between ‘real’ voices and synthetic ones becomes all but impossible. But such a faithful re-creation would do little to tell us about how lines would be delivered.

Bourdain may ask his friend the question about happiness in a tone that is playful, angry, melancholic, disgusted, or a myriad of other possibilities. We simply have no way of knowing, nor does Neville. By using the AI-deepfake to voice Bourdain, Neville is imbuing meaning into the chef’s words – a meaning which is derived from Neville’s interpretation and the black-box of AI-algorithmic functioning.

Roadrunner is a poignant example of an increasingly ubiquitous problem – how can we trust the world around us given technology’s increasingly convincing fabrications? If we cannot be sure that the words within a documentary, words that sound like they’re being said by one of the most famous chefs of the past twenty years, are genuine, then what else are we justified in doubting? If we can’t trust our own eyes and ears, what can we trust?